You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

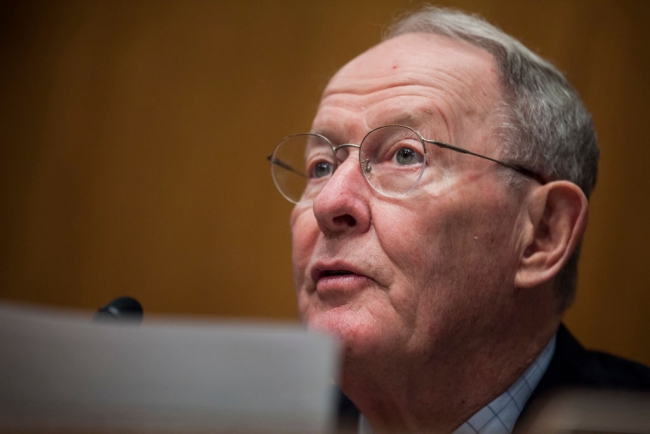

Senator Lamar Alexander, chairman of the Senate education committee

Getty Images

Senator Lamar Alexander, the chairman of the Senate Health, Education, Labor and Pensions committee, said Monday that he will not seek re-election in 2020.

His decision could have big consequences for a reauthorization of the Higher Education Act as well as congressional approaches more broadly on issues like student loans and college accountability.

Alexander, 78, said earlier this year that he hoped to make quick progress on a new higher ed law. But even after a series of detailed hearings, talks with Democrats in the Senate never got serious. He was already facing a term limit as committee chairman in two years. Now Alexander’s retirement plans may add more urgency to reach a deal on the renewal of the key law governing financial aid and many other higher education programs and add another signature accomplishment he's long targeted as chairman.

“I will not be a candidate for re-election to the United States Senate in 2020,” he said in a statement. “The people of Tennessee have been very generous, electing me to serve more combined years as governor and senator than anyone else from our state. I am deeply grateful, but now it is time for someone else to have that privilege. I have gotten up every day thinking that I could help make our state and country a little better, and gone to bed most nights thinking that I have. I will continue to serve with that same spirit during the remaining two years of my term.”

Alexander is one of a handful of lawmakers with experience as a college president. Also before being elected to the Senate, he also served as Tennessee governor and U.S. education secretary under President George H. W. Bush. That résumé in education policy has gone unmatched by Alexander’s peers in Congress.

In the Senate, he’s been known as a bipartisan deal maker as a well as a legislator with an intense interest in the higher education system. His biggest legislative achievement was the 2015 passage of the Every Student Succeeds Act, a “fix” to the No Child Left Behind law, which he co-wrote with Senator Patty Murray, his Democratic counterpart on the HELP committee. More recently, he helped restore year-round Pell Grants last year.

But his relationship with Murray appeared strained after a tense confirmation process for Education Secretary Betsy DeVos last year. Murray and other Democrats argued for more hearings to scrutinize DeVos's record, a demand that Alexander rejected. For many observers, that process didn't bode well for bipartisan cooperation on a higher ed bill.

Terry Hartle, senior vice president for government and public affairs at the American Council on Education, the top Washington lobby group for U.S. colleges, said that Alexander has made it clear for several years he would like to pass a new comprehensive higher ed law as well, and predicted that the decision to retire will only increase his desire to get it done.

“But the fact is they didn’t get too close last year with Republicans controlling both the House and the Senate,” Hartle said. “The bigger and the more complicated the legislation, the harder it is to do it in the current environment. That’s just the world we’re living in.”

One of Alexander’s long-running goals has been an overhaul of the Free Application for Federal Student Aid, or FAFSA, which students must complete to qualify for Pell Grants and student loans. He’s famously made the paper application a frequent prop in committee hearings and other public events to underscore how long and complicated it is.

Simplifying the process to apply for student aid is a goal shared by congressional Democrats as well. But disagreements over how to restructure student loan repayment options and accountability rules for colleges have slowed any serious talks about a bill. In February, Alexander released a white paper suggesting current government accountability measures were inadequate and unfair to for-profit colleges. House Democrats, by contrast, this summer introduced a plan to reauthorize the Higher Education Act that would preserve Obama-era higher ed rules like borrower defense and gainful employment.

If Alexander and congressional Democrats do reach a compromise on a new law, they’ll have a long way to go to reach middle ground.

But Tamara Hiler, deputy director of education at the think tank Third Way, said Alexander’s retirement announcement is the clearest indicator yet that the Higher Education Act renewal will be a priority in 2019.

“He has already demonstrated the ability to work well with Senator Murray in a bipartisan fashion, and without having to worry about the prospects of managing a political campaign and re-election, he will be even more focused to work across the aisle to get this legislation through,” she said.

Senate Leadership

Alexander’s departure will leave a big void in the Senate. But there are a handful of Republicans on the committee with a track record of bipartisan higher ed legislation, said Emily Bouck West, deputy executive director at Higher Learning Advocates and a former staffer for GOP senator Marco Rubio. Georgia senator Johnny Isakson has worked with Delaware Democrat Chris Coons on the ASPIRE Act, which would pressure wealthy colleges to enroll low-income students. And Louisiana senator Bill Cassidy was one of the earliest co-sponsors of the bipartisan College Transparency Act, which would produce more data on higher ed outcomes.

Alexander, though, brought to Congress a knowledge of the Education Department's earliest years and some of its biggest challenges. Bill Hansen, president and CEO of Strada Education Network, said he was the first to put in place national goals for education at the department.

“He was really a pioneer in helping to shape the Department of Education,” said Hansen, who served under Alexander at the department.

Alexander also entered the department when the federal student loan program was experiencing major turmoil. Loan default rates had risen throughout the 1980s as the Reagan administration starved the department of resources, said ACE’s Hartle. Default rates exceeded 20 percent before Alexander started at the agency. He responded by stepping up policing of the program and rebuilding the Education Department’s oversight capacity.

And Alexander in 1992 helped shepherd an HEA reauthorization bill that included reforms to the loan program designed to cut down on defaults.

“His retirement is a huge loss for America’s colleges and universities,” Hartle said. “There’s no other way to look at it.”