You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

DAYTON, Ohio -- Learning societal rules about touching and personal space is the lesson of the day in Heidi Arnold's interpersonal communications class.

“How many of you were raised in a touchy-feely house?” she asks her class of 17 women.

Two arms, both covered in plain blue shirts, shoot into the air.

The communications class is part of the business pathway program at Sinclair Community College. To many of the women, it’s one of the most challenging classes they have taken. Arnold is teaching them the types of skills employers demand of workers in middle-skill professions.

A tap on the shoulder or a hug mean different things to a colleague than to our children, Arnold tells the class.

“The rules of haptics,” she says explaining the concept of physical communication.

On the front wall of the classroom, just above the whiteboard, are three sentences in bright, large lettering: “Make a difference. Make it happen. Make it right.”

That’s the goal for every one of the women in Arnold’s class. They’re attempting to make it right -- "it" being the crimes that landed them in Dayton Correctional Institute in the first place.

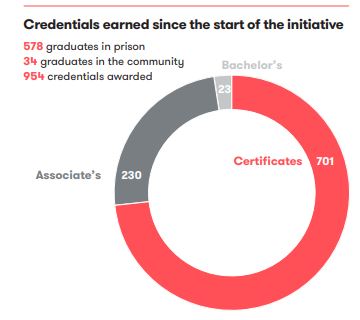

The class is part of Sinclair's prison education program. For 31 years the college has given incarcerated men and women an opportunity to earn certificates -- and associate degrees at one point -- to help them achieve those three sentences once they’re released.

Two-thirds of job postings will require some level of college education by 2020, according to the Lumina Foundation. And educators and policy makers increasingly agree that offering certificates and degrees to prisoners may be one of the best first steps to helping them re-establish their lives and be less likely to reoffend in the future.

But government funding for such programs is sporadic at best. The 1994 crime bill signed by President Bill Clinton banned incarcerated students from receiving federal student aid. That left it up to states and colleges to figure out the best way to pay for these programs. Many collapsed in the law's wake.

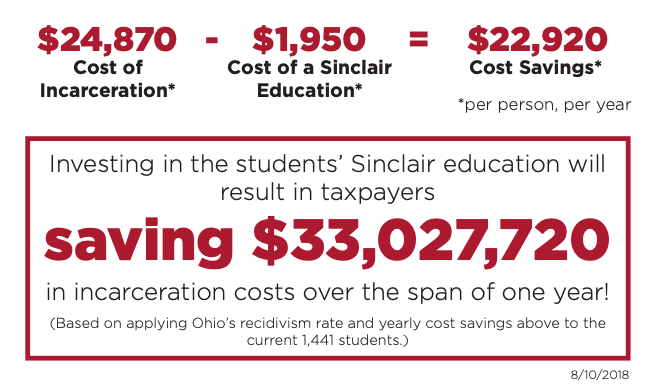

Some prisoners -- and their families -- pay tuition out of pocket, and others receive funding through state correctional departments. For example, Sinclair is reimbursed by the Ohio Department of Rehabilitation and Corrections an average $1,950 for every student the college educates. But the 1994 ban led the college to stop offering associate-degree programs to inmates to keep costs down.

In recent years, a growing number of universities and community colleges have been seeking awareness of their prison education programs and calling for more funding to help inmates earn degrees. And those efforts appear to be working as bipartisan support emerges in Washington for such programs.

“The bottom line is that there are about 2.4 million incarcerated people, and 95 percent of them are coming out at some time,” says Dan Phelan, president of Jackson College, a two-year institution located in Michigan. “We have a choice. We can let them come out and a number of them will do something to get back in prison … or we can do what the RAND Corporation pointed out: when inmates have an educational experience, they’re less likely to recidivate.”

In a widely cited 2013 study, RAND found that by reducing recidivism, taxpayers save $5 for every $1 spent on prison education. In comparison to the annual $1,950 per student Ohio spends to reimburse colleges for educating inmates each year, the average inmate costs the state about $26,000 a year, according to the Vera Institute for Justice. And multiple studies have found that inmates who receive an education are 43 to 72 percent less likely to reoffend.

“We believe from a moral point of view we have to assist them,” Phelan says. “They’re paying their debt to society and we’re giving them the essential skill sets they need so they can leave and become employed and contribute to the tax base and provide for their family.”

Funding Prison Education

Jackson College is among 65 two- and four-year institutions that are participating in the Second Chance Pell Grant program. Launched in 2015 by the Obama administration, the program gives colleges and the U.S. Department of Education flexibility to award federal aid to incarcerated students.

- 43 percent to 72 percent: Impact of prison education programs on chance a participant will be incarcerated again

- 400 percent: Return on investment over three years for taxpayers, or $5 saved for every $1 spent

- About 50 percent of incarcerated people have a high school degree or equivalent

- Two-thirds of job postings will require some level of postsecondary education by 2020

- At least 95 percent of incarcerated people will be released at some point

Sources: National Reentry Resource Center and Vera Institute of Justice

The Trump administration supports the experiment, which is funded through 2019, and is examining how to better evaluate its results. The results could help Congress decide whether to lift the ban on federal funding, which would mean programs like the one at Sinclair could return to offering associate degrees.

Cheryl Taylor, the coordinator of Sinclair’s prison education programs, says the college could serve many more potential students with more funding. There are 28 prisons in the state, of which Sinclair is only in 10.

Michigan does not provide funding for educating inmates, which means that prior to the Second Chance program, many convicts and their families covered the cost of tuition.

The college was granted more than 1,300 Pell Grants to award to inmates as part of the federal experiment. About 600 prisoners are participating in the program, Phelan says.

Lumina is funding an initiative at California's San Quentin State Prison to develop a set of benchmarks to help states and funders evaluate the best ways to educate incarcerated people.

Haley Glover, strategy director for the foundation, says no helpful resources exist to identify which states fund higher education in prisons and how well states are positioned to offer funding.

“There is a really vibrant community of practitioners focusing on how do they maintain and sustain these amazing programs, and they’ve been evaluating them all this time,” she says. “There is no shortage of evidence that says they really work.”

Glover says policy makers and educators know anecdotally that the benefits extend beyond lowering recidivism rates, including increased earnings for families and ex-convicts who are more engaged in civic life. But research on those benefits is lacking.

Sinclair's prison education program, for example, saves taxpayers more than $33 million each year in avoided incarceration costs.

As the U.S. labor force requires more people with college degrees and certificates, some colleges and states consider incarcerated people a largely untapped work-force resource that could help increase educational attainment rates overall.

“Completion is a part of it, but honestly I believe the state believes it’s the right thing to do,” Taylor says. “The value is in seeing lives change and having opportunities that weren’t afforded to them. Giving them and equipping them with the ability to be the people they were meant to be.”

In the state of Ohio, about 70 percent of prisoners don’t have a high school diploma. But Sinclair’s prison education program has a 92 percent completion rate, she says.

Back in Arnold’s classroom at Dayton Correctional, when the 17 student inmates were asked who had made the dean’s list, every hand raised in the air.

The Impact, and a Guided Pathway

Earning a college credential helps convicts prepare for life outside prison. And for some, it's an opportunity to have a life they could never have had before prison.

Dayton Correctional has housed women inmates since 2012. More than 800 are behind its bars today.

Erin Noll is one of those prisoners.

“Without this, I would literally be leaving 11 years later to a whole new world,” says Noll, an inmate who has already earned a certificate in social services from the college and is currently in Sinclair’s business pathway. “I’ve never been an adult outside of here. I’ve never had a job. I’ve never paid a bill. I’ve never done none of these things.”

Noll has spent almost all of her adult life behind bars. She spent time in juvenile detention as a teenager and in 2009, at age 17, she was charged and convicted for aggravated robbery and burglary after committing several home break-ins.

She describes her life prior to being incarcerated as tough. Her mother, who has been sober for the past 10 years, was a drug addict at the time. So Noll grew up with her father. But she says, she was sexually assaulted between age 4 and 11 by a family member. That family member and her father remained close friends despite her family’s knowledge of his actions. Noll says this damaged her relationship with her father.

“I started getting into trouble a lot and I started skipping school,” she says. “I didn’t think my life was going to go anywhere.”

A Day in the Life of a Student Inmate

Shauna Stumm is not the typical college student.

But the 37-year-old Dayton Correctional Institute inmate, who was indicted for burglary and will be released in 2021, has what could be viewed as a traditional day for many community college students.

She starts her mornings around 7 a.m. by getting dressed and making a cup of coffee for herself before going to work.

In prison, Stumm’s job is as a maintenance apprentice. The role isn’t connected to the college but is offered through the prison.

“I have to be at work at 8 a.m., and generally I’ll work on different odds and ends -- things like painting, laying tile, putting in screens … different things like that,” she says.

By 2 p.m. Stumm and the other inmates will have “count time,” which is when guards count each inmate in the facility.

“For me that’s key,” she says. “Because that’s the only time that I’m forced to sit down and be still. So, I sit in my room during count and do my homework … There's no distractions. There’s nobody bothering me.”

On the days she doesn’t have to work, Stumm spends her mornings studying with another student inmate, Erin Noll.

Stumm, who is on Sinclair’s business pathway, plans to earn a bachelor’s degree eventually and to open her own deli.

“I always wanted to go to college," she says, "but I became a young mother and a young wife and was not able to follow through with that."

Stumm, who has two teenage daughters and an 11-year-old son, said she dropped out of high school as a junior and later earned her GED. But with two decades having passed since the last time she was a student, Stumm was nervous about going back to college.

“I thought, ‘Is this going to be too much for me?’” she says. “But after getting into it, I realized it wasn’t.”

From 5:30 to around 8 p.m., Stumm attends Sinclair classes in the prison.

After that there’s dinner and back to her room to sleep.

“For me, as a woman, this feels empowering,” Stumm says. “I’m getting to do something that, through my poor choices, I’m actually able to pull something positive out of something negative. It’s something that I have for myself that I can be proud of.”

Like many prison education programs, inmates are not allowed to apply for the Sinclair program until they are five years away from their release date.

“I was young and on the prison scene, and that's a scary thing,” she says. “I’ve watched so many people come in and out of here. I would watch other women go to college or school and I would just watch.”

Noll didn’t think the program was for her. But after seeing other women take advantage of the opportunity, she decided to apply and take an entry assessment to determine her skills. She passed and was accepted in the program.

“I’m like, ‘I’m in, oh gosh, now I got to do it,’” she says. “Six semesters later and I think it’s the greatest decision I’ve ever made.”

Noll is scheduled to be released next year. She jokes about her lack of knowledge of gadgets and the latest technology -- Noll's the rare Millennial who has never used a smartphone. The Motorola Razr was popular when she was first locked up.

“Without the education in here, I think I would be walking out of here blind,” she says.

Noll knows how she wants to use her certificates when she’s released from prison next year, although even the thought of life outside is a bit scary.

“It’s hard when you live in here to try and think about outside of here,” she says. Noll hopes the credential helps take her to a career working with children and in social services.

“I want to work with troubled youth,” Noll says. “I know it might take a while to get to that point, so I really want to focus … I hope to have my bachelor’s degree in four years. I just really want to give back, and I want to be able to show people that people can change.”

Taylor, the Sinclair coordinator, says community and social services is one of the more popular programs among inmates, perhaps unsurprisingly. She says many who have dealt with drug addiction want to turn to social services work as a way of helping others avoid making the same mistakes that they did.

“A lot of them want to enter the help professions,” she says, adding, however, “The help professions don’t pay a lot unless you earn a master’s degree, but supply chain management in Ohio is a large industry.”

Sinclair instructors encourage the student inmates to take classes that interest them, but they also guide them to enroll in programs that will lead them to jobs that pay a living wage once they are released. The college estimates that supply chain management jobs will increase at a rate of 22 percent over the next several years. Noll enrolled in the program after completing her social services certificate.

Sinclair’s business pathway and entrepreneurship certificate is another popular program among inmates.

“You know having a felony on my record, I just think it’s going to be kind of hard to get employment,” says Tracee Burton, who is 54. “So I decided I’ll start my own business.”

Burton, who was convicted of felony assault, has been in Dayton’s prison for about four years and is scheduled to be released in just a few months. She’s interested in starting a business selling all-occasion gift baskets for holidays and celebrations.

But she doesn’t intend to stop going to college, even after she’s released.

“This is going to be an ongoing thing for me,” she says. “Even if I have to take one class at a time. Once you get your feet wet, it’s like, ‘OK, I’m ready.’ I just want to learn everything.”

Instructing Student-Inmates

Dayton’s prison houses inmates whose security level ranges from Level 1, which is the lowest security risk and grants the most amount of privilege and autonomy, to Level 4. Level 5 is maximum security, followed by death row.

Looking past the barbed-wire fencing that envelopes the facility, the institution looks like a large high school or small college campus, with sidewalks carrying visitors from one building to another.

But before moving from one section of the prison to another, guests, staff and employees must pass through a set of sliding metal doors into a small holding room. There they wait for the heavy metal clink of the first door to slide closed, as a second door slides open.

Taylor says the sound of those doors closing the first time can be unnerving for instructors.

Sinclair has about 80 faculty members, both adjunct and full-time, who teach in the prison program. The level of access instructors receive inside a prison varies widely. Some wardens allow instructors to bring in approved materials. Prison classrooms may have computers, but it’s rare to find an internet connection. As a result, the Ohio Department of Higher Education purchased tablets for the program so instructors can preload information for students to download.

Faculty members who teach in prison education programs must make adjustments, says Laura Hope, executive vice chancellor of the California community college system.

“Every college running a prison program is committed to making sure the students have the same accredited, rigorous degree or certificate experience as they would have on a college campus,” Hope says. “It does mean they have to be creative and overcome challenges.”

For example, Lyndsey Adams, an adjunct faculty member in Jackson’s prison education program, makes adjustments to her science lab when she teaches in prison. She works with the Michigan Department of Corrections to make sure that everything she brings is appropriate for inmates.

“A lot of the beakers and equipment had to be plastic. We couldn't have digital balances and had to use an old-fashioned balance. Thermometers couldn’t have mercury. I couldn’t bring in acidic liquids to cut rocks,” she says. “We had to compromise.”

Instructors often make compromises in the prison setting and sometimes get criticism from colleagues about the effects these changes have on the curriculum.

“In the past, we’ve gotten pushback,” Adams says. “We have people challenging whether the classes are rigorous enough. Every teacher goes into a facility and teaches classes the same exact way they would teach them on the outside.”

Bobby Beauchamp, director of the prison education initiative at Jackson, says the college is pretty good about alleviating concerns from faculty members about teaching in prisons. He says many instructors would rather teach all of their classes in the prison than on campus. The college employs about 60 faculty members in its prison programs, he says.

Getting In, and Getting Out

The process for applying and enrolling in a prison education program varies from college to college and state to state. But some aspects of the programs cross those boundaries. For example, many require that inmates be five years or less away from release, although some just require that inmates aren't on death row.

In Michigan, Phelan says, wardens analyze each inmate who applies for the program and recommends them to Jackson. California's community colleges run application sessions in prisons, Hope says.

“Marrying these two bureaucracies is challenging,” says Hope, referring to the corrections and education systems. “People get transferred, disciplinary issues arise, people drop out because life happens to people in prison just as it does to people outside of prison. The college and the prison work together to basically monitor that cohort of students and keep them enrolled in the college program.”

Adams, the Jackson instructor, said a common criticism she hears is that student inmates should not have a problem being successful in their college courses because they have nothing but time to master and complete them.

“That drives me crazy, because unless you’ve been in a prison, you can’t truly appreciate the challenges they face,” she says. “I have parents still trying to parent their children inside of prison … the living is crowded, there’s no privacy, no quiet place to study, there may be officers who don’t want them to be successful and inmates who don’t want them to be successful … I can’t imagine those challenges.”

Hope says the biggest hurdle may be transfers between prisons.

“A court order may happen and they’re transferred 200 miles away to a prison that may not have an educational program like the one they were in,” she says.

The California system is working on an associate degree pathway that would follow transferred inmates.

While many student inmates earn their degrees and certificates behind bars, others complete their education once they’re released. And even when they don’t, colleges and organizations help them with the transition.

Last year, Phi Theta Kappa, the national honor society for community college students, extended its membership to students who are incarcerated or on parole.

"You look at the mission of Phi Theta Kappa and it's to recognize academic excellence -- it's not to pass judgment," said Lynn Tincher-Ladner, the organization's president and chief executive officer. "We want to recognize their academic excellence and set them up with opportunities."

By extending membership to inmates and ex-convicts, the honor society also made these students eligible for scholarships to pursue bachelor's degrees.

Taylor, the Sinclair coordinator, says the college works with parole officers who often call administrators to verify that former inmates are continuing with their studies and attending courses on the outside.

“We look at ourselves as partners in how to help this individual succeed,” she says.

The same is true in other states where colleges with prison programs often work with parole boards to help students with their release.

Beauchamp says Jackson provides a letter to parole boards to highlight inmates’ accomplishments in the classrooms, as well as their transcripts.

Kristi Fraga is a former inmate at Women’s Huron Valley Correctional Facility, which is located in Ypsilanti, Mich. She enrolled in Jackson’s prison education program and graduated with her associate degree earlier this year.

Fraga, who was a drug addict, was imprisoned in 2011 after being convicted of assault and theft.

“I use my story to change the way people view felons,” she says. “I completely acknowledge and take responsibility for my past … I realized the only way I could make amends was to better myself.”

When Fraga enrolled in Jackson’s courses in 2014, the Pell program wasn’t available. But her family was willing to pay the tuition. The college charges $762 in tuition for up to five credits, $1,524 for six to eight credits, $2,286 for nine to 12 credits and $3,048 for 12 credits or more.

Parole rules vary from state to state. But Fraga faced challenges after her release in May 2017.

“The parole process dictates you go back to the county you came from or a suitable placement with a person who has a decent home,” Fraga says.

Fraga is from Michigan’s Upper Peninsula. And while her family does support her, she says they were not willing to take her in as a newly released inmate.

“It was going to be community placement for me. And in my county, there are three seedy motels, all of which I bought drugs from,” Fraga says. “I was terrified to be released in that situation, especially less than a year from my degree.”

So she reached out to an acquaintance in Hillsdale who allowed her to stay in her home. That meant Fraga could be paroled at Hillsdale and complete college at Jackson's Hillsdale campus. Fraga is now a student at the University of Michigan. She works as an economics tutor at Jackson College.

“I got out May 3, and by the second week of May I was in school,” she says. “Going to Jackson after being released has been crucial to my success, even to staying sober. I found value and purpose in my life.”