You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

WASHINGTON -- Eric Schultz, an associate professor in the department of ecology and evolutionary biology at the University of Connecticut, hopped on a bus at 1 a.m. Saturday and headed here with about 50 students and faculty members from the university.

He said the March for Science was about communicating with the general public, which he said does not appreciate what science does and why it’s valuable.

Assessing the March's Impact

Organizers and participants say

the event's legacy may be told

in federal funding levels for

science programs. Read more.

Schultz’s work is primarily funded by the National Science Foundation, with some support from the National Institutes of Health and the Environmental Protection Agency. Were the cuts to those agencies in the White House budget released last month to become reality, he said, his department could lose the ability to support graduate students.

“That means we’re selling out our future essentially for the sake of weapons,” Schultz said.

***

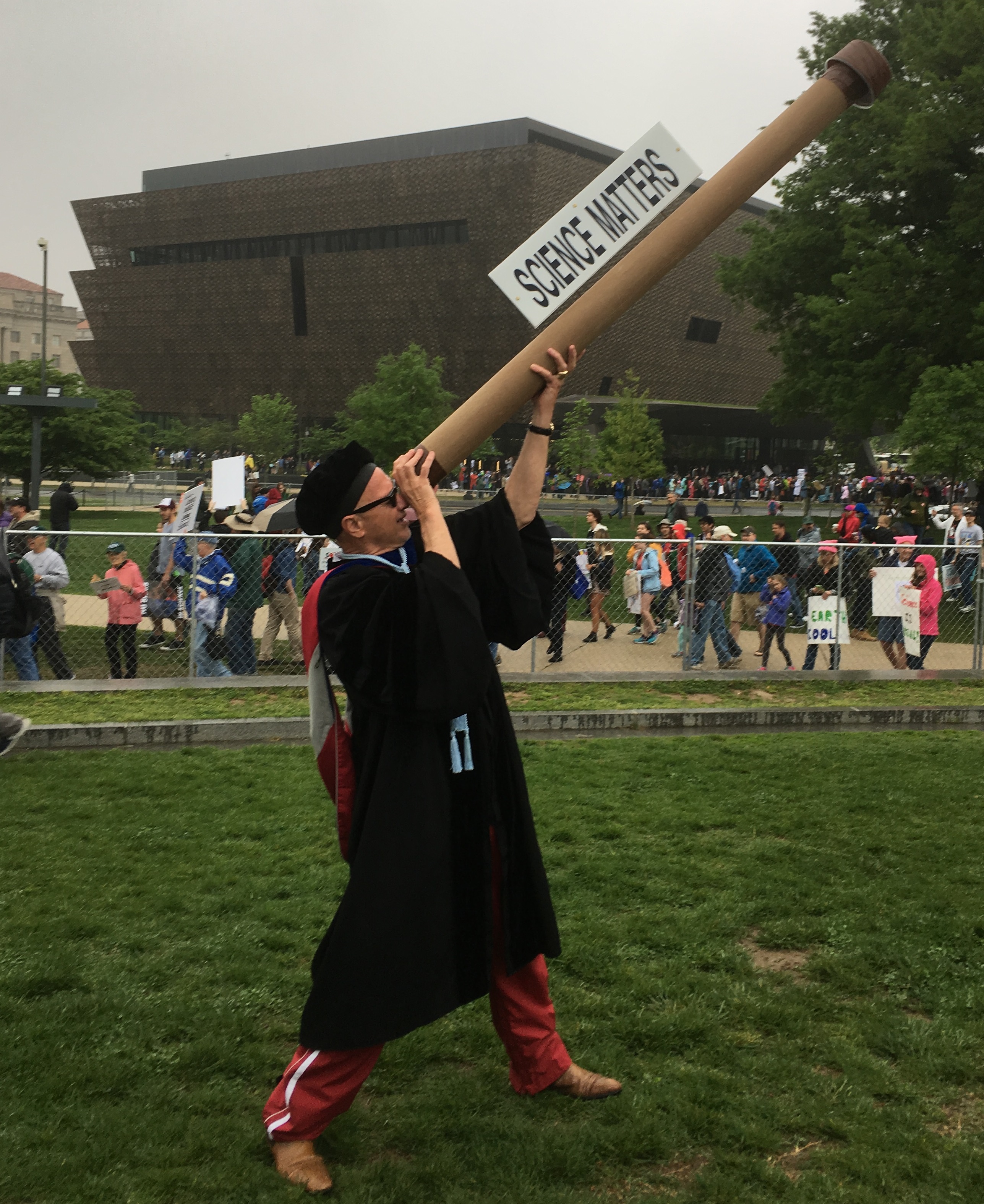

John Kilbourne, a professor in the department of movement science at Grand Valley State University, couldn’t go far on the National Mall Saturday without a request for pictures. Kilbourne came to the march dressed as Galileo, who he said spoke up for scientific truths even though he knew he would be persecuted for it.

Kilbourne studies the traditional games of indigenous people in the Arctic and looks for lessons to help moderate conflict in that region today. He said he was motivated to come to the march partly because of the administration’s disregard for the science of climate change, the effects of which indigenous people are experiencing firsthand.

“For the most part, scientists have stayed on the sideline,” he said. “We need to speak up.”

***

More than a hundred Cornell University graduate students traveled via bus Friday to participate in the Washington march. Gael Nicholas and Kofi Gyan were among them.

Nicholas, who is studying biochemistry with a focus on the microbiome, said the effects of cuts in federal support of research trickle down from labs to the ability of graduate students to pursue research.

Gyan, who is studying computational biology, said he is an optimistic person and hopes to see Congress continue federal funding of research.

“You can’t be red or blue with science,” he said. “I’m just here supporting science because I love it.”

***

Steven Hanes, a professor at State University of New York Upstate Medical University, wore a cardboard sandwich board reading “Want Cures? Support Basic Research” to the march Saturday.

Hanes, who studies molecular genetics, has been unable to train any new graduate students in his lab for the past three years since his NIH funding lapsed. He said he was marching this weekend because of the proposed further cuts to NIH and NSF research funding the White House proposed in its “skinny budget.”

If Congress votes to keep research funding flat, it will be seen as a victory by many -- but it will still essentially be a cut because funding has not kept up with inflation, Hanes said. The tight budget environment for university-based funding means winning grants to pay for science and train graduate students is already extremely competitive, he said.

“If we don’t train the next generation and support that research, we’re going to lose them,” he said.

***

Four women, most of whom are pursuing their doctorates at Indiana University, drove 11 hours to the march.

Olivia Ballew, Annie MacKenzie, Tiffany Musser and Ali Ordway all were selected and given stipends by the university to cover their travel costs. They said they were pleased to represent the university.

All but Musser are in the midst of earning th

Their signs were sketched out on poster board -- one carried a Neil deGrasse Tyson quote: “The good thing about science is that it's true whether or not you believe in it.”

Soni Lacefield, a biology professor at Indiana, also traveling with the group, said the demonstration places science in a positive light and brings awareness to legislators.

The march breaks down stereotypes and stigmas associated with the scientific community, and helps put a face on scientists.

“It’s not just old white men sitting in a dusty laboratory,” Ballew said. “We are diverse.”

***

In a dark green T-shirt, Charles Agosta almost seemed to blend in with the vast swaths of grass on the National Mall, especially compared to the highlighter-yellow ponchos and massive protest signs that dotted the landscape.

But up close the text on the shirt was much bolder: National High Magnetic Field Laboratory, a facility at Florida State University where the Clark University professor of physics does some of his work on superconductivity. He came to the D.C. march with his son -- they stopped along the way to look at colleges in New York, Pennsylvania and Michigan.

His curly hair fluffy from the continued drizzle, Agosta explained how the age range of the attendees impressed him -- students, but also the more “mature” crowd, scientists of his generation.

Among the young people was Agosta’s 17-year-old niece, a high school junior who wants to be an astronomer, he said.

Agosta’s not sure how she caught the science bug, as her parents aren’t oriented in the sciences.

A movement like the march is something that scientists should be organizing more and more, not just as a demonstration for the Trump administration, but to celebrate the sciences, Agosta said.

These types of gatherings among scientists are fairly unusual, he said.

Debate has arisen about whether “politicizing” the sciences is appropriate, he said. But everything is political -- everyone lobbies for federal funding -- but science shouldn’t be partisan, he said.

“Stay curious!” a speaker from the main stage screamed in the background.

***

As she stood in the rain clutching her stark sign on a white board that read “Science is crucial for democracy,” Toni Bell said she was disgusted.

The professor of chemistry and biochemistry at Bloomsburg University of Pennsylvania is fed up with funding being pulled from scientific organizations. She can’t “wrap her head around” science money being channeled toward other parts of the federal government.

In an interview, she hesitated. “Well, to fund the military. I wasn’t going to say it outright,” Bell said. “But to pull money from science education and the arts to fund the military. That just hurts me to my core.”

“We have to do something about it. We cannot let it stand.”

She traveled to D.C. from Pennsylvania with a bus full of people from Bloomsburg -- a relatively rural, conservative area anchored by the university -- along with a Bloomsburg chemistry professor, Kristen Lewis.

Because Bell is rooted in a university environment, people respect the sciences, she said. But she was heartened to see so many community members from the area travel here.