You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

NYU Shanghai

Clay Shirky stares into the camera in front of him as he reaches the core of his argument.

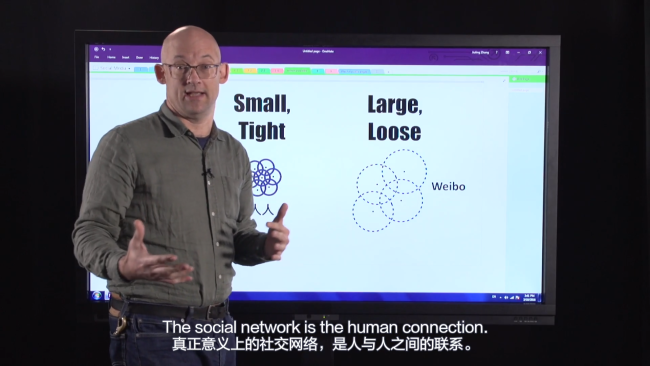

“The social network is the human connection,” the associate professor of journalism at New York University and writer of all things internet says, turning to highlight an illustration on a digital blackboard of large and small clusters of connected users on social media. “The social network service allows for and encourages some kinds of connections and disallows or discourages other kinds of connections.”

Below him in the frame, two sets of captions -- one in English, the other in Chinese -- appear.

Instructional designers at NYU’s Shanghai campus, where Shirky is currently teaching, recently created a series of brief informational videos on social media to test how they could more effectively offer content online in the country. To their surprise, the videos attracted more than 100,000 views in only a couple of days. The university is now expanding the experiment with more videos, viewing them as a way to increase its visibility, market itself to teenagers and their parents and -- perhaps one day -- offer credit-bearing hybrid courses.

The videos can be seen as an extension of NYU’s mission to become a “global network university,” with campuses and academic centers in a dozen foreign countries. While the videos began as an internal video production experiment for faculty members, the feedback is helping the university understand how it can better serve Chinese students, who make up about half of the Shanghai campus’s enrollment, as well as others who might never enroll in NYU’s full American-style degree programs.

China’s expanding middle class and its hunger for higher education -- as well as its ability to pay full price for tuition -- presents a tantalizing opportunity for many colleges and universities based in the U.S. But because of censorship, language and technical issues, however, beaming content to students in China is for most colleges a nonstarter.

NYU Shanghai’s videos are an attempt to tackle some of those challenges, Shirky said in an interview.

The first major challenge is easy enough to guess: the language. While the videos are in English, NYU Shanghai hired a firm to ensure the Chinese subtitles read naturally and capture the technical information correctly. Running an English script through an online translation service -- Google Translate, for example -- isn’t just inadequate, Shirky said; it could embarrass the university in the eyes of its Chinese viewers.

The translation firm can only do so much with the content it is given, however. NYU Shanghai is planning to release a new video series later this summer, but Shirky said the firm struggled with the instructor’s style of speaking -- frequently jumping from one idea to the next and back again in the course of a single sentence. Chinese speakers simply don’t structure sentences that way, Shirky said.

Video composition also matters, the university has learned. NYU has a treasure trove of video content that has been recorded over the years, and some of it could likely be repurposed for a Chinese audience, Shirky said. But slapping subtitles on old lecture videos won’t work, he added. The university has learned from its experiments that Chinese viewers are more interested in shorter videos where an instructor speaks not to students assembled in a physical classroom, but directly to a viewer. Its videos on social media follow that design principle, using a digital blackboard as a backdrop so Shirky can make eye contact with the camera.

“We don’t need these things to look like Hollywood blockbusters, but we do need the language to be acceptably high-quality that people watching the video think, ‘They’re talking to me,’” Shirky said. Releasing a video with sloppily translated captions, he said, would be “almost worse than if you didn't do it in the first place.”

The second challenge is more difficult to spot, unless you’re located in China. Internet speeds in China are notoriously slow -- especially for content coming from outside the country. Course lectures hosted by colleges in the U.S. or on popular video platforms such as YouTube, once they travel through China’s congested network infrastructure, become a stuttering mess to viewers there. NYU Shanghai solved that problem by hosting the videos on three Chinese content delivery networks, Shirky said.

In addition to language and technical issues, there are also cultural differences universities should keep in mind when creating content for Chinese students, Shirky said. Unlike in the U.S., for example, the widespread popularity of the internet and smartphones in China occurred at the same time. The term “mobile first” truly applies, in other words, meaning universities should design content that looks good on smartphone displays.

“The large-scale challenges we knew from the beginning,” Shirky said. “The surprises are all these small-scale things.”

Shirky, who teaches about social media, said he spends some time each week talking to Chinese teenagers about their social media habits. A handful of themes have emerged from those talks, including the popularity of the messaging app WeChat and social video sites where users produce content rather than just consume it.

Still, Shirky said, “I couldn’t point you yet to where this stuff will matter …. The silly stuff comes first, and then people figure out what it’s good for.”

The university will continue to experiment with videos without the expectation that they will soon generate revenue, Shirky said. If they continue to prove effective at attracting viewers, he added, the videos could one day be included in hybrid courses that mix face-to-face and online instruction.

“You can experiment more when you don’t have to justify credit,” Shirky said. “Outreach is good, making high school students and parents aware is good, and it may be in a place in the future where we use [the videos] in course materials.”