You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Getty Images

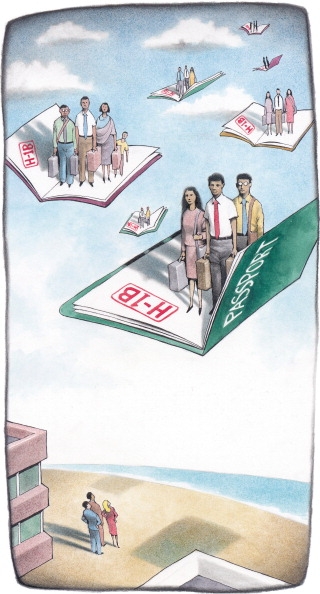

The H-1B guest worker visa program has been coming under scrutiny lately.

The program is important to colleges both in terms of their ability to hire postdocs and other researchers from abroad and, more indirectly, in providing a pathway for the international students they recruit to work in the U.S. after graduation. Many in higher education see the existence of such pathways as important in making the U.S. an attractive destination for international students, especially since some countries that compete with the U.S. for top graduate student talent offer easier and more straightforward routes from student to permanent residency status.

But several national news articles have raised concerns about the use of the H-1B visa program to displace American workers in the corporate sector. And Wright State University, in Ohio, reported in August that federal authorities are investigating possible violations in its use of the H-1B program. The president and board chair for Wright State University wrote in a statement that they had been “presented with credible evidence that somewhere between two and five years ago not every H-1B employee sponsored by the university was actually working at the university. That would violate federal law, and it concerns us greatly.”

In response, Wright State has demoted the provost and a director of business process re-engineering from their administrative posts (both retain their faculty positions), fired a staff member who served as senior adviser to the provost, and negotiated a $300,000 separation agreement with the general counsel, who then retired.

University employers like Wright State are exempt from statutory caps limiting the number of H-1B visas, currently set at 65,000 per year. An additional 20,000 H-1Bs are reserved for holders of advanced degrees from U.S. universities.

The H-1B is an employer-sponsored visa for workers in “specialty occupations,” typically those requiring at least a bachelor’s degree in a related field. Although it is a temporary visa, it can be a stepping-stone on the way to permanent residency.

The program has often been described as a way for Silicon Valley companies to attract “the best and brightest” engineers and scientists from abroad, and is seen as a key tool in helping companies fill high-demand jobs for which there are insufficient numbers of qualified candidates who are U.S. citizens. However, the top recipients of the visas are outsourcing or consulting companies, many based in India, which, as The New York Times reported in June, “import workers for large contracts to take over entire in-house technology units -- and to cut costs.” The Times was reporting on the use of the H-1B program to displace American technology workers at the Walt Disney Company. In some cases the laid-off American workers had to train their replacements.

The Los Angeles Times has reported on similar concerns surrounding the power utility Southern California Edison’s decision to contract with two of the largest outsourcing firms, Infosys and Tata Consultancy Services, for tech-related work at the same time it planned to lay off hundreds of employees. In a statement to Inside Higher Ed, Southern California Edison said it has reduced its information technology department from 1,400 to about 860 employees as of mid-2015. “By transitioning some IT operations to external vendors, along with SCE eliminating some customized functions it will no longer provide, the company is focused on making significant, strategic changes that can benefit our customers,” Southern California Edison’s statement said. “It is important to note that SCE’s contracts with IT vendors Infosys and TCS require those companies to comply with all applicable laws and, specifically, those requiring valid and appropriate work authorizations for their employees performing services in the United States under contracts with SCE.”

The H-1B visa has also made an appearance in the campaign for the Republican presidential nomination. As part of his immigration platform, front-runner Donald Trump called for raising the prevailing wage paid to foreigners on H-1B skilled worker visas and putting in place a requirement that employers hire American workers first.

“Congress and multiple administrations have inadvertently created a highly lucrative business model of bringing in cheaper H-1B workers to substitute for Americans,” Ron Hira, an associate professor of public policy at Howard University said in testimony before the Senate Judiciary Committee in March. “There are mainframe-sized loopholes built into the H-1B program's design … and a complete disinterest on the part of multiple administrations in enforcing the current rules, however weak they may be.”

“I’ve always said, let's amend the H-1B program, let's not end it,” Hira said in an interview. He has, for example, called for raising the minimum wages paid to H-1B workers (in his Senate testimony he described current rules requiring that H-1B employers pay a “prevailing wage” as “poorly designed and written”).

Vivek Wadhwa, a fellow at Stanford University’s Arthur & Toni Rembe Rock Center for Corporate Governance, is a big supporter of high-skilled immigration. But even he’s “not a fan of the H-1B visa as it's being used right now.”

“By having these outsourcing companies get the visas, start-ups in Silicon Valley basically are gasping for air. They're taking oxygen out of the system; they're taking visas away from companies that could be innovating and could be having a very positive impact on the economy,” said Wadhwa, who is also director of research at Duke University’s Center for Entrepreneurship and Research Commercialization.

“We do need more visas, without doubt, but we need to figure out how to curb this abuse and basically have higher standards for who we bring in here,” Wadhwa said.

“I would basically remove any caps for graduates of American universities,” he continued. “Why limit it? If they've graduated from one of our universities and companies want to hire them, let them be hired. These are people we want in our economy.”

A bill introduced earlier this year that was endorsed by major higher education associations would nearly double the total number of H-1Bs available, from 65,000 to 115,000, and lift the cap altogether on the number of H-1Bs granted to holders of advanced degrees from U.S. universities. The Immigration Innovation, or “I-Squared,” bill would also exempt holders of advanced STEM degrees from U.S. universities from the cap on employment-based green cards.

Hira, however, questions the wisdom of making universities “gatekeepers” to permanent residency status. “The notion that the only qualification for getting a green card is getting a master's degree [from a U.S. university] seems like a bad idea to me in many, many different respects,” he said.

“The only reason it would be a good idea from a national interest perspective is if indeed there were a shortage of such people, but I don’t think there’s any evidence of that except in some small fields, or fast-growing fields,” said Michael S. Teitelbaum, a senior research associate at the Labor and Worklife Program at Harvard Law School. Teitelbaum is the author of Falling Behind: Boom, Bust, and the Global Race for Scientific Talent, in which he argues that, contrary to conventional wisdom, there is no evidence of a generalized shortage of STEM workers in the U.S.

Others argue that there is evidence of such a shortage. In an analysis of STEM workforce trends from 2008 to 2018, the Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce forecast that the total number of STEM degree holders (2.6 million) will fall short of the total number of STEM job openings (2.8 million) for the 10-year period (the calculation of STEM graduates is for all higher education levels, from certificate programs to Ph.D.s, and is adjusted to account for labor force participation rates).

“We believe that the 200,000 number for the shortage of STEM workers is a lower limit,” Nicole Smith, the center’s chief economist, said via email. “This is because STEM graduates tend to ‘divert’ into various non-STEM fields due to the high demand for STEM competencies outside of traditional STEM occupations. As a result, STEM wages remain high and many workers move out of STEM to other lucrative opportunities -- thus adding to the vacuum of the shortage of STEM bodies.”

“In many STEM areas, foreign students are a majority of the Ph.D. graduates from U.S. universities,” a coalition of 14 major higher education associations wrote in their letter endorsing the I-Squared Act. “Yet despite the obvious need for the skills offered by these graduates, our outdated immigration system forces many of them to leave, sacrificing the innovation and economic growth they would create here.”