You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Steven M. Gillon of the University of Oklahoma teaching his new U.S. history survey course offered in conjunction with the History Channel.

U of Oklahoma

The University of Oklahoma raised some eyebrows last year when it announced it was partnering with the History Channel to offer a new U.S. history survey course. The thrust of the initial interest was the university’s decision to pair up with a relatively old-school medium -- cable television -- to offer distance learning in the midst of a digital platform boom. But after a successful first run of the course, another story has yet to be told: that of history faculty members’ lingering distaste at what they call being left out of the process and, more generally, at the university partnering with a commercial entity now perhaps better known for reality TV shows such as Ice Road Truckers and Swamp People than college-level history. Proponents of the partnership, meanwhile, tout the channel’s top-rate archives and audiovisual capabilities, as well as its mission to make historical study more accessible.

“This is the best introductory history class I’ve ever taught,” said Steven M. Gillon, a professor of history at Oklahoma who spends much of the year in New York City, where he is the History Channel’s longtime historian in residence. “This has completely changed my perspective of [distance learning].”

Gillon said he’d been trying to pitch some version of the course -- a survey of U.S. history from 1865 through the present, heavy on historical videos and images -- for 10 years, but never quite found the right home. The course grew legs last year, he said, when administrators at the university talked to him about a joint course with the History Channel. They announced the venture in October, and a first session was offered over the winter term. About 50 Oklahoma students enrolled, along with 25 outside students who took the course for credit and some 60 additional lifelong learners.

Those who earned college credit for the course paid $500 (enrollment is currently discounted to $449), and noncredit enrollees paid $250 (currently $149).

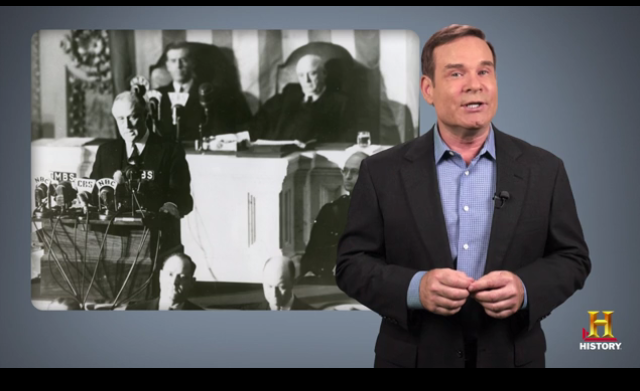

The course is now enrolling students for summer sessions. Topics include industrialization and urbanization, the Gilded Age and progressivism, World War I, the Cold War, Vietnam and Watergate, the Reagan era, and the U.S. in the 21st century. Here’s a sample lecture dealing with World War II.

The survey is based on 16 hours of lectures Gillon wrote and delivers, supplemented with various media from the History Channel, which is part of A&E. Staff members from the university’s Center for Teaching Excellence helped design the course, which is offered through the university’s Janux interactive learning platform. (Janux is part of NextThought, staffers of which also participated in the project.)

In addition to watching lectures, students are expected to read 50-100 pages per week of a textbook Gillon wrote for the course and offers to students for free. They also complete online discussions and other assignments. Gillon interacts with students and answers questions, but another lecturer does the grading.

Gillon said he thought on-campus, in-person learning was still optimal for upper-level courses, especially those that are heavy on building research skills. But because he’s always viewed distance learning as “anything beyond the 10th row,” he said, the History Channel course format is surprisingly intimate and, above all, engaging.

“The lectures I deliver in this class -- these are the same lectures I’ve given forever, but unlike those lectures I don’t always team up with a group of producers to produce these visuals. We’ve found images and parts of documentaries that reinforce the themes and key points.”

Mark Morvant, director of the Center for Teaching Excellence, said the course was unique on college campuses in that it drew on visual “assets” the History Channel’s been amassing for decades. “This is not just Steve Gillon talking about the course or lecturing. There’s archival footage and videos, which increase the richness.”

‘Devaluing’ Oklahoma’s History Major?

But not everyone at Oklahoma is bowled over by the course. Some historians say their department should have been consulted before the university affiliated it with a commercial entity that is these days is arguably as much in the pop entertainment business as it is involved in promoting history. Two of the channel’s most popular shows, American Pickers and Pawn Stars, for example, chronicle the exploits of junk and antique enthusiasts. As the blog Gawker once put it in a headline, “The History Channel’s Secret to Success: No History.” (Of course, the History Channel still offers lots of historical programming, and it’s perhaps unfair to blame a network for its viewers’ preferences.)

“I think that the History Channel is a fine TV program, but their purpose is to make money. …Their job is not to do academic history and they don’t,” said one Oklahoma professor of history who spoke on condition of anonymity, saying the affiliation has embarrassed the department. “I’ve had a lot of folks contacting me saying, ‘What is this? What kind of department are you part of?’ Their take on it is that this is a pop history class that kind of makes a mockery of the university.”

Ultimately, the professor said, “This type of class runs the risk of devaluing [Oklahoma’s] history major. Folks have reassured me that this is not the case, but as I write students letters of recommendation for graduate and professional schools, I am very conscious of the value of their degree.”

Ben Keppel, an associate professor of U.S. history at Oklahoma, said he was “strongly opposed to having either the history department or the University of Oklahoma collaborating with this for-profit commercial entity.”

Keppel added via email, “Until this collaboration was disclosed on the university's website last fall, I was a regular viewer of the History Channel, especially Counting Cars and Pawn Stars. Those are fun shows, and they no doubt they turn a profit for A&E and the History Channel. Teaching history as a crucial academic endeavor to the constructive preservation and regeneration of human societies, however, is not about turning a profit and keeping people ‘satisfied.’”

Instead, Keppel said, “You teach history best by mastering the most important primary sources that a society has created and fully understanding contexts and conflicts. To do this job well, any history department and any university needs to remain independent of what the History Channel is all about. There is nothing heinous about what they do, but it is not what we do.”

Keppel declined further comment, but the unnamed history professor said some faculty members were concerned with how the course was presented to the department as a fait accompli -- although they did successfully negotiate a cap for Oklahoma students. The course counts as a full three-credit class for Oklahoma students.

The professor also questioned the amount of promotional attention from the university the course had received, saying it vastly outpaced that for any other humanities course. She wondered where the profits for the course were going.

For the record, the university and the channel will split tuition revenue down the middle; the university will put its profits back in the general fund, a spokesman said.

Laura Gibbs, an online instructor of mythology and folklore at Oklahoma, also has criticized the course. Gibbs said in an interview she was suspicious of the university’s open enrollment policy for the American history course, while at the same time making most of the content private. By contrast, she said, all of her course content is open access, but to enroll students must be accepted to the university -- not just “pony up” a credit card.

But perhaps the biggest problem with the course, she blogged, is the university’s marketing it as “immersive,” while it in her view fails to live up to that term.

“This is simply a cookie-cutter video-driven course in which students watch videos, read the written materials that accompany the videos and then participate in discussion boards, just like in online courses 10 years ago,” Gibbs wrote in October. “Because there is a discussion board, the marketing people describe the class as dynamic, interactive, engaging, etc. Presumably the course earns the title 'rigorous' because of the two short papers. As for the rest of the hyperbole -- pioneering, groundbreaking, singular, unique, like no other, etc. -- it's just the usual marketing fluff. I'm not really even sure how effective that kind of fluff is anymore, but it certainly seems to be inevitable.”

James S. Hart, chair of the history department, was traveling and not immediately available for comment.

Gillon said he found much of the criticism of the course -- including whispers that he’s less a member of the department because he’s based primarily in New York -- unfounded.

“I'm a tenured, full professor in the history department with an appointment in honors,” he said. “That gives me the right to teach classes and represent the university. I have taught on campus for the past 17 years. If my current students all lived in Norman, then I would continue to teach on campus. But the vast majority of students taking this online class live somewhere else.”

He added, “That is one of the great advantages of an online class -- it allows you to create a virtual community of students that is not bound by region or geography. What matters is that I am available to my students every day. In fact, I have more daily interaction with my online students than I ever had with my on-campus students.”

Gillon said the History Channel has had absolutely no editorial interference in the course, and he encouraged his colleagues in the history department -- some of whom said they’d been admittedly slow to embrace online courses -- to experiment with the format. He said it makes higher education more accessible, which serves everyone.

Saying that the course was aimed at attracting more students from off campus than on, he said he understood his colleagues' sensitivities but thought they were largely "misplaced."

Kyle Harper, senior vice president and provost at Oklahoma, in a statement called Gillon an “accomplished historian and dedicated teacher, who wanted to make a truly special online class by bringing the ‘sights and sounds’ of the History Channel's rich archive into his lectures.” Harper called the course an “innovative experiment” that’s under Gillon’s complete direction.

So is there a problem with the History Channel doing academic history? James Grossman, executive director of the American Historical Association, said no, in general. (He also offered the disclaimer that the channel sponsors an event at the organization’s annual conference.)

“Sure, much that appears on the History Channel is not what I would write or teach,” Grossman said via email. “Different venues, whether they be television, commercial tourist attractions, children's books, national parks or classrooms, offer people different kinds of history. I am pleased that Americans are so eager to engage history, and fully recognize that they will engage different kinds of history in different ways. The AHA maintains standards for professional historical work. But we don't license. History Channel and other purveyors of popular histories play a vital role in stimulating and nourishing American's interest in the past. This is a good thing.”