You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

NEW YORK -- Work-life balance might seem like an oxymoron to overworked faculty members, but an increasing number of institutions are trying to help their professors achieve it. So what policies are valuable and how can they effectively be included in union contracts? Those were some of the questions central to a panel discussion on negotiating work-life balance here Tuesday at the annual conference of the National Center for the Study of Collective Bargaining in Higher Education and the Professions at the City University of New York’s Graduate Center (the National Center is housed at CUNY’s Hunter College).

At the University of Massachusetts at Amherst, negotiating balance came down to data. Joya Misra, professor of sociology and public policy at UMass, said her administration agreed to update some of its faculty contract provisions following a comprehensive study of its faculty. If that sounds familiar, Misra and her coresearchers have written about some of their findings. An article debunking the idea that men exploit parental leave policies to bolster their research portfolios instead of bonding with their children gained particular attention; the unnamed university in that study was in fact UMass Amherst.

As part of a working group related to the campus’s National Education Association-affiliated faculty union, Misra and her colleagues successfully surveyed and tracked the work habits of 349 tenure-line and non-tenure-track faculty members. They also conducted smaller focus groups for non-tenure-track faculty, assistant and associate professors and librarians. (The faculty has about 1,200 tenure-line professors and some 200 non-tenure-track faculty.)

Misra said she thought she’d be at the high end of the work spectrum at 65 hours weekly, but it turned out she was just the mean -- “smack-dab in the middle.” UMass faculty members reported working 60 hours or more, including a substantial portion of the weekend. Also surprisingly, she said, most professors expressed a concern about “work-work” balance -- or determining how much time to spend on research versus, say, service -- over work-life balance. In other words, faculty members needed as much or more help balancing their research, teaching and service as balancing their work and personal lives.

"Some people have jobs that finish when they leave. We don’t,” one faculty member observed.

Another remarked, “When can you say no? …How will this be taken? Will it jeopardize my career?”

Others expressed concerns about the heightened expectations for tenure. One reported hearing from a dean that a successful tenure bid would require “10 letters from Nobel Prize winners and Academy of Science members saying you are the top person in your field.”

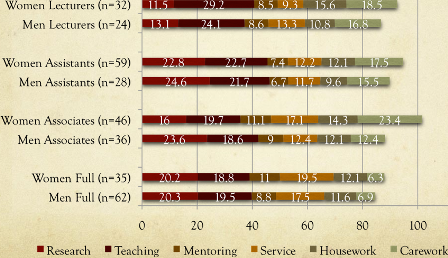

The survey found that work time is heavily weighted toward teaching, mentoring and advising students -- and that that work is gendered. While they do not substantially reduce their time spent on teaching, mentoring or service, mothers spend 7.2 fewer hours per week on research than fathers. Men with young children, meanwhile, tend to “protect” their research time. (Misra said that lesbians without children did the most service, suggesting that higher expectations exist for women who don’t have a husband or children at home).

The study revealed even more dramatic gender differences in time faculty members devote to unpaid work at home, such as caring for children, partners or aging parents. Fewer women than men have children, but faculty mothers are primary caregivers for children more often than faculty fathers. When work, housework and care time are totaled, Misra said, women at every rank put in much longer days than men.

Weekly Duties and Time Spent Reported by UMass Amherst Faculty Members

Source: Joya Misra and Jennifer Lundquist

But both men and women reported feeling the squeeze between work and home. One male faculty member said, “My son said, ‘Dad, you are not here when I need you these last four years.’”

Another professor reported feeling guilt about spending more time at home, saying, “I refuse to lose that time with my daughter, and I feel like I am slacking on my job.”

Another said, “Balance is an inappropriate term. I sat on a seesaw.”

Gender differences emerged again in looking at who took parental leave. Some 72 percent of new mothers take leave (89 percent in non-science, technology, math and engineering fields versus 70 percent of mothers in STEM). Just 28 percent of fathers took parental leave, with no difference between STEM and non-STEM faculty members. Fathers who were primary or equal caregivers in the household often did not take paid leave, but Misra noted that the subset of surveyed men who had taken paid leave was admittedly small (23 individuals).

Most contract faculty members were beyond childbearing years when they became eligible to take paid leave, after six years of continuous, full-time service.

Misra said UMass's administration was interested in the data, particularly because it might have implications for its ability to recruit and retain top faculty. This is something of a problem, again due in part to UMass’s rural location, she said. So the union and UMass negotiated various policy changes.

First, said Jennifer Lundquist, an associate professor in Misra’s department and one of her coinvestigators, there were revisions to the parental leave policy to include more non-tenure-track faculty. Formerly, senior lecturers had to work six years to apply for paid leave; now it’s three.

There’s also now automatic parenthood tenure clock stoppage, and child care subsidies for new junior faculty (up to $3,000 per year for three years). There are new child care funds -- about $1,000 annually -- for meeting attendance in STEM.

There have been additional, informal shifts in some units and departments, Lundquist said, such as child care at college events or planning department meetings for midday instead of late afternoon, when parents are picking kids up at school.

Lundquist said these changes and existing policies make UMass one of the nation’s best universities for work-life balance. But she said it’s important that faculty members know about such programs through awareness efforts, as even the best initiatives mean little if they’re not used. Dean and chairs got a “tool kit” of ideas through which to promote these policies, she added.

John Bryan, associate provost for academic personnel at UMass, said the union made some “persuasive arguments.” He said he knew the faculty union wanted “even more progressive policies,” but that he thought UMass was still “ahead of the curve.” That leads to greater job satisfaction and higher retention rates, he said, “so all of this we see as being justifiable because it is an investment” in the faculty.

Lisa Bonick, executive director of academic labor relations and an administrative liaison to the faculty for Rutgers University at New Brunswick on work-life issues, said her institution’s newly negotiated contract with the AFT- and American Association of University Professors-affiliated faculty and graduate student worker union contains important updates to work-life balance provisions. Some were suggested by a committee on work-life issues formed following the last round of contract negotiations, in 2009; Bonick said many of the concerns raised by that committee were similar to those raised in the UMass study. The Rutgers faculty union includes tenure-line and non-tenure track professors, as well as librarians.

Under the contract, for example, the birthing parent gets six weeks of paid recuperative leave, and both parents get eight additional weeks of paid leave. (Research faculty members get compensated for any paid committee service.) Departments have an opt-out clause for undue hardship, Bonick said, but no department has ever successfully argued to her a case against leave for a faculty member.

A new provision says that the six- and eight-week leaves don’t have to be used consecutively. Also new is that the parental leave can be banked for up to 12 months after the contract, as not to disadvantage parents of children born in the spring or summer.

Rutgers’s newest contract includes a “closing ranks” provision in which departments may extend faculty members' leaves for extenuating circumstances, such as when a parental leave is due to end close to the end of a semester, but usually when a faculty member falls ill. In that scenario, the faculty member continues to receive full pay and benefits, but the provision must be applied equitably and consistently across the department.

There are additional provisions for unpaid leave for caretaking or personal illness, and faculty members within the first five years of their probationary periods may request a tenure-clock stoppage.

Audience members at the National Center conference applauded the provisions achieved, but some wondered about the possibility of provisions that don’t assume faculty members have children. What about planning a vacation for a professor who doesn’t have time, for example, one wondered.

Misra said her institution had an established Employee Assistance Program, but that that’s used more for self-care. She said single faculty members on campus reported wanting more work-life provisions catering to their lifestyles, too.