You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Getty Images

First, the good news: Full-time faculty member salaries grew somewhat meaningfully year over year -- 1.4 percent, adjusted for inflation, according to the American Association of University Professors’ Annual Report on the Economic Status of the Profession, out today. Not adjusted for inflation, that’s about 2.2 percent across ranks and institution types, and 3.6 percent for continuing faculty members in particular. Those numbers are almost identical to last year, when pay bumps outpaced the rate of inflation for the first time since the Great Recession, suggesting that professor salaries have started to recover.

Now the bad news, according to the report: faculty salaries remain much lower than many of those in the business world, and make up just a fraction of institutional expenditures, yet many Americans continue to blame professor pay for ballooning tuition. (Think Vice President Joe Biden’s 2012 remarks about “escalating” academic salaries, or more recent suggestions from Wisconsin Governor Scott Walker about increasing professor productivity in the face of a proposed $300 million state funding cut to higher education -- as well as University of Wisconsin at Madison Chancellor Rebecca M. Blank’s snappy response.)

A.A.U.P. tries to correct that perception about professor pay, among others, in this year’s faculty salary survey narrative, called “Busting the Myths.” While full-time faculty salaries have actually decreased 0.12 percent since the recession, adjusted for inflation, net tuition has risen 6.5 percent on average across institution types, the report says. Over the same period, A.A.U.P. says -- narrowing in on what it identifies as the real reason for skyrocketing tuition -- state appropriations have decreased 16 percent on average. And endowments have “eroded,” too.

“The need to reclaim the public narrative about higher education has become increasingly apparent in recent years as misperceptions about faculty salaries and benefits, state support for public colleges and universities, and competition within higher education have multiplied,” reads the A.A.U.P. report. “Rebutting these misperceptions can aid in organizing to achieve economic security for all faculty members -- full time and part time, on and off the tenure track.”

But first, a little more on this year’s data:

By the Numbers

A.A.U.P.’s report includes data on full-time faculty salaries from 1,136 responding institutions. The study does not include part-time professor pay, so keep in mind that those adjuncts who are part time -- many of whom face flat wages on a lower base and who have the least chance of getting a raise -- are not counted.

That limitation notwithstanding, A.A.U.P.’s full-time faculty salary data are more current and comprehensive than anything available elsewhere, including from the federal government. Inside Higher Ed is the exclusive provider of A.A.U.P.’s current faculty salary survey and full data sets are available here. Institution-specific top-10 lists -- such as where full professors earn the most -- are at the bottom of this article.

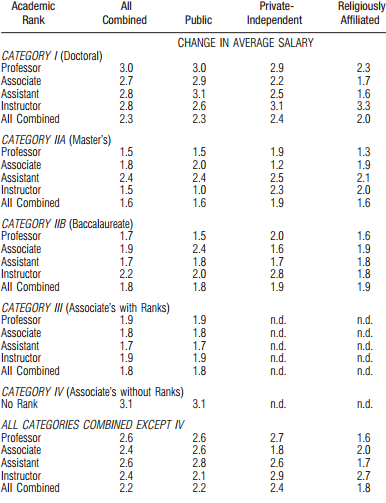

Breaking down salary data by institution type, faculty members at doctorate-granting institutions got the biggest raises between 2013-14 and 2014-15: 2.3 percent, not adjusted for inflation, compared to 2.2 percent over all. In a change from last year, when they fared worst among their colleagues, full professors at public research institutions saw some of the biggest raises: 3 percent (continuing full professors specifically got 3.4 percent raises). They were closely followed by their full professor peers at private research institutions, who got a 2.9 percent raise (continuing professors alone saw 3.3 percent pay bumps). Fully professors at religiously affiliated, doctorate-granting universities got a 2.3 percent raise.

Associate and assistant professors and instructors at doctorate-granting institutions did almost as well, with a few exceptions: associate professors at religiously affiliated universities saw just a 1.7 percent pay bump, for example.

At master’s degree-granting institutions, assistant professors got the biggest pay increase: 2.4 percent, on average, with little difference between public and private institutions. The faculty pay increase over all for these colleges and universities was 1.6 percent.

At baccalaureate institutions, instructors -- full-time, non-tenure-track faculty -- saw the biggest raises, at 2.2 percent, on average across institution types. The average combined pay increase for all faculty members was 1.8 percent.

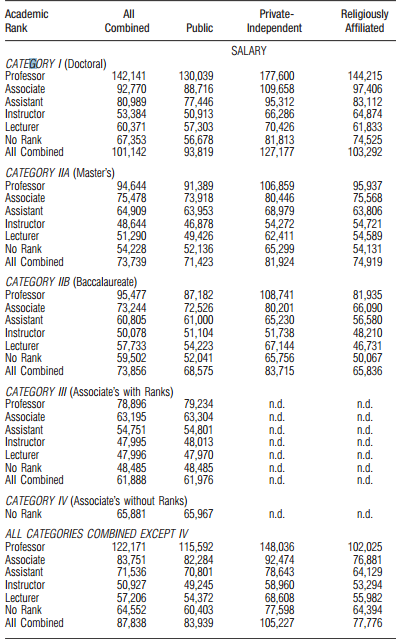

So how much does that amount to? On average, full professors at public institutions earned $115,592, while their colleagues at private, nonreligious institutions earned $148,036. Full professors at religiously affiliated colleges earned $102,025.

Associate professors at publics earned $82,284, while associate professors at privates earned $92,474, and those at religious institutions earned $76,881.

Assistant professors at public institutions made $70,801. Assistant professors at private institutions made $78,643 and they earned $64,129 at religiously affiliated institutions.

Lecturers earned $54,372, $68,608 and $55,982, respectively.

As is the case year after year, male professors made more than women even when comparing faculty of comparable rank; experts attribute this to demographic differences among higher- and lower-paying disciplines, implicit bias in hiring and promotion, and other factors. Across institution types and ranks, men made $95,886; women made $77,417.

Also following tradition, faculty members in New England earned more than their counterparts elsewhere: $105,385 across ranks and institution types. West Coast professors made $97,395, on average, followed closely by their colleagues in the mid-Atlantic, at $96,374. Professors in the North Central, Western Mountain and Southern U.S. earned significantly less, from about $77,500 to $84,000.

‘Busting the Myth’

Despite modest gains, A.A.U.P. says in the narrative portion of the report, professor pay can’t be blamed for rising tuition. In reality, the report says, the decline of state appropriations for higher education and the “erosion” of endowments have hiked up the price of college.

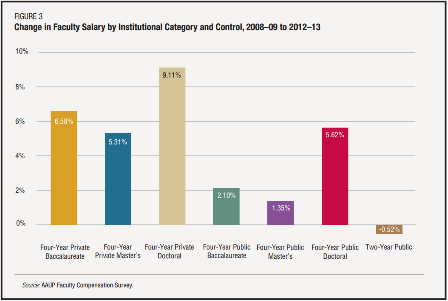

“If faculty salaries were largely responsible for increases in average net price tuition [the cost of attendance minus grant and scholarship aid], then we would expect to see spikes in faculty salaries that far exceed the percentage increases in average net price tuition,” the report says. On the contrary, net price tuition rose 5.3 percent between 2008-9 and 2012-13, while faculty salaries virtually stagnated, it says. Even at private, doctorate-granting institutions, where faculty salaries have risen the most since the recession -- about 9.1 percent, not adjusted for inflation -- that’s still less than the overall net price tuition increase of 9.2 percent.

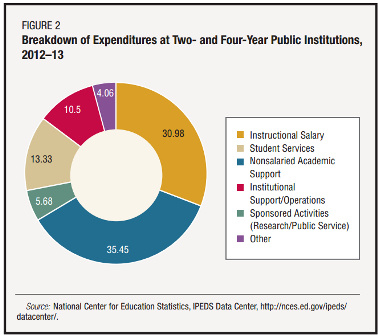

Put another way, instructional salaries at two- and four-year institutions make up just 31 cents on the dollar of the institutional budget, the report says. (It’s important to note that that figure, based on data from the Department of Education’s Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System, includes contingent faculty salaries, which are typically low and therefore may artificially shrink the proportion.)

So if not faculty salaries, what is driving tuition increases? A.A.U.P. avoids a lengthy discussion of sports and the growth of administrative ranks, which were the focuses of last year’s salary survey report, and instead points to decreased state funding for public colleges and struggling endowments for private colleges.

The report offers a state-by-state list of percentage change in appropriations to higher education from 2008-9 to 2012-13. While such information is publicly available (the appropriations data are from the Center for the Study of Education Policy at Illinois State University) and has been widely reported, some of the numbers remain startling: New Hampshire, down 62 percent, correlated with a 10 percent net price tuition hike over the same period; Oregon, down 37 percent, and a 13 percent tuition jump; and Louisiana, down 50 percent, and 18 percent higher tuition, for example.

Not every state cut correlates with a big jump in tuition, and some states actually managed to drop their net price tuition through restructuring or other means. Across the 50 states, though, the trend is clear: state funding declined 16 percent and net price tuition went up 6 percent.

Among private institutions, A.A.U.P. says that endowments took about a 20 percent hit during and immediately after the recession, and are only now beginning to recover.

A.A.U.P.’s report also tries to bust the myth that faculty members are overpaid. It says that the association is contacted throughout the year by members of the media who invariably ask if professors make too much for too little work, a narrative that’s supported by opinion pieces and other accounts similar to what former New School Chancellor David Levy wrote in The Washington Post in 2012: “Though faculty salaries now mirror those of most upper-middle-class Americans working 40 hours for 50 weeks, they continue to pay for teaching time of 9 to 15 hours per week for 30 weeks, making possible a monthlong winter break, a week off in the spring and a summer vacation from mid-May until September.”

Levy was talking about faculty at teaching-oriented institutions, not those with research-heavy positions, but lots of faculty members across institution types disagreed with him. “Busting the Myths” says that faculty members even at teaching institutions can work 50- or 60-hour weeks, and that “even the high-ranking professors are generally underpaid,” relative to their peers in industry. An astronomy professor, for example, makes $101,900 annually, according to included data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics, while an astronomer makes $109,300. A math professor makes $78,500, while a mathematician outside academe makes $124,450, while a law professor makes about $126,000 and a lawyer makes $138,000. (A.A.U.P.’s selected examples include no examples in the humanities or social sciences.)

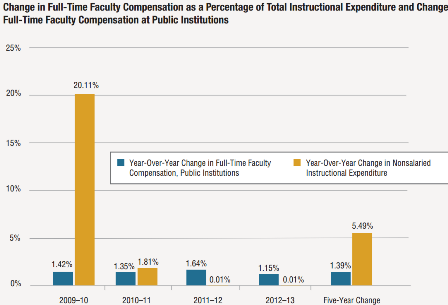

A.A.U.P. also challenges a third “myth” that the faculty must move away from the tenure and full-time faculty system to effectively deal with “disruptive technologies,” since data suggest that part-time faculty members with little institutional support are less effective educators for that reason. The report also says that colleges and universities have spent relatively little on these technologies and related faculty training in recent years, except for a spike in 2009-10. So rather than shedding tenure-line faculty positions with no real investment in competitive technology, A.A.U.P. says, colleges and universities would better protect their turf by exploring “strategies to improve budgeting, incorporating greater technological innovation in education with faculty involvement, efficiently managing specialization and stabilizing part-time faculty through conversion.”

One last “myth” addressed in the report is that faculty benefit costs are “out of control.” In reality, A.A.U.P. says, costs for faculty benefits aren’t significantly increasing and the cost of benefits as a percentage of compensation has increased just 1 percent a year for the past five years.

Defending Professor Pay

John Barnshaw, senior higher education researcher at A.A.U.P. and lead author of the report, said he thought it was important to set the record straight because “a lot of people have preconceived notions” about professors’ lifestyles, particularly as tuition continues to strain or evade the budgets of average families.

“When people look around, they see very clearly that tuition is on the rise -- they can feel it,” he said. Because faculty members are often the most visible people on campus, he said, “students might assume that they’re all well compensated and in fact better compensated than their peers anywhere else, and that’s why they stay in academe. But of course that’s probably not the case.”

Barnshaw said it was important to correct the record with data, he said, and encouraged readers of the report to share it with colleagues, friends and even state and federal legislators through social media and other means.

Ken Redd, director of research and policy analysis for the National Association of College and University Business Officers, said he agreed with A.A.U.P.’s assertion that professor pay is not driving up tuition. Significant drivers are state disinvestment in higher education -- despite a much criticized recent New York Times op-ed arguing otherwise, he said -- and the growth of administrative ranks as colleges and universities struggle to oversee new federal mandates and programs. Redd disagreed with A.A.U.P.’s claim that still-struggling endowments are driving up tuition, however, saying that they’ve largely recovered from blows they took during the recession, especially within the last two years.

Gary Rhoades, professor and director of the Center for the Study of Higher Education at the University of Arizona, said he thought the report helped address some of the misperceptions about faculty pay. One of the most valuable findings in particular, is that professor salaries make up less than one-third of institutional budgets, he said. “I would say that most people do not know that.”

At the same time, Rhoades said the report could have done more to bust the myth that professors are overpaid by further revealing the stratification between disciplines -- think law versus the humanities, for example -- and professors at elite institutions and those at, say, “East Nowhere U.” Many faculty members at the vast majority of less and nonselective colleges and universities make far less than the reported averages, he said.

Touching on a common, year-after-year criticism of the report, Rhoades added that data on part-time faculty pay -- even if it had to be taken from outside sources -- is essential to understanding the faculty pay landscape.

Barnshaw, who is new to A.A.U.P. this year, said finding ways to incorporate part-time faculty pay information is a top priority.

“That’s 73 percent of the labor force,” he said of non-tenure-track faculty, many of whom are part time (about 58 percent of instructors over all). “We’d like to see the survey expand in that way in the future.”

Individual Institutions

Beyond general trends and A.A.U.P.’s take on the data, lots of academics look to the annual faculty salary survey for institution-specific information, such as where professors earn the most. That said, the data don’t take into account important factors such as variations in cost of living -- likely the reason why many of the highest-paying institutions are in or near large cities. Nor do the average salary data reveal stratification based on disciplines, even within the same institution. So, similar to Rhoades's point, keep in mind that faculty in the humanities, for example, might earn much less than business, medical, engineering and other professors at a given college or university.

This year's top 10 list for private research universities (the best paying category by far) is made up of the same institutions as last year's list, with some shuffling, including at the top: Stanford University displaced Columbia University as number one.

Top Private Universities for Faculty Salaries for Full Professors, 2014-15

|

University |

Average Salary |

|

1. Stanford University |

$224,300 |

|

2. Columbia University |

$223,900 |

|

3. University of Chicago |

$217,300 |

|

4. Princeton University |

$215,900 |

|

5. Harvard University |

$213,500 |

|

6. Yale University |

$198,400 |

|

7. University of Pennsylvania |

$197,500 |

|

8. New York University |

$196,900 |

|

9. Massachusetts Institute of Technology |

$193,900 |

|

10. Duke University |

$193,300 |

As has been the case in previous years, the top institution for public pay would not make the top 10 for private pay. The University of California at Los Angeles tops this list, as it did last year. Four other University of California campuses (Berkeley, San Diego and top 10 newcomers Santa Barbara and Irvine) also make the list.

Top Public Universities for Faculty Salaries for Full Professors, 2014-15

|

University |

Average Salary |

|

1. University of California at Los Angeles |

$181,000 |

|

2. New Jersey Institute of Technology |

$174,500 |

|

3. University of California at Berkeley |

$172,700 |

|

4. University of Michigan at Ann Arbor |

$160,900 |

|

5. University of Maryland at Baltimore |

$157,000 |

|

6. University of Virginia |

$156,900 |

|

7. University of Maryland at College Park |

$154,200 |

|

8. University of California at San Diego |

$153,900 |

|

9. University of California at Santa Barbara |

$152,800 |

|

10. University of California at Irvine |

$152,600 |

The top liberal arts colleges for pay for full professors are very similar to lists from the past several years.

Top Liberal Arts Colleges for Faculty Salaries for Full Professors, 2014-15

|

College |

Average Salary |

|

1. Claremont McKenna College |

$161,500 |

|

2. Wellesley College |

$154,300 |

|

3. Barnard College |

$154,100 |

|

4. Pomona College |

$148,600 |

|

5. Amherst College |

$145,100 |

|

6. Harvey Mudd College |

$142,200 |

|

7. Wesleyan University |

$141,500 |

|

8. Williams College |

$141,200 |

|

9. Swarthmore College |

$141,000 |

|

10. Colgate University |

$140,000 |

This year, the data show 23 colleges and universities where the average salary for an assistant professor tops $100,000. That's up from 19 institutions last year, and 11 the year before.

Colleges With Six-Figure Salaries for Assistant Professors, 2014-15

|

University |

Average Salary |

|

1. Stanford University |

$122,500 |

|

2. University of Pennsylvania |

$119,600 |

|

3. California Institute of Technology |

$118,900 |

|

4. Babson College |

$117,900 |

|

5. Massachusetts Institute of Technology |

$114,300 |

|

6. Columbia University |

$114,100 |

|

7. Harvard University |

$113,300 |

|

8. Bryant University |

$112,700 |

|

9. University of Chicago |

$112,300 |

|

10. New York University |

$111,200 |

|

11. Bentley University |

$108,000 |

|

12. Northwestern University |

$106,900 |

|

13. Carnegie Mellon University |

$106,100 |

|

14. Duke University |

$105,400 |

|

15. University of Texas at Dallas |

$105,200 |

|

16. Princeton University |

$104,600 |

|

17. Georgetown University (tie) |

$103,300 |

|

17. Cornell University (tie) |

$103,300 |

|

19. University of California at Berkeley |

$103,000 |

|

20. Northeastern University |

$102,200 |

|

21. Washington University in St. Louis |

$102,000 |

|

22. Dartmouth College (tie) |

$100,100 |

|

22. Drexel University (tie) |

$100,100 |