You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

For years, experts on the academic and scientific workforce have talked about a "leaky pipeline" in which women with talent in science and technology fields are less likely than men to pursue doctorates and potentially become faculty members.

A study published Tuesday in the journal Frontiers in Psychology says that the pipeline may no longer be leaking more women than men. The study suggests that academic science may be losing a lot of talent -- men and women alike -- so the leaky pipeline metaphor may still be valid. But it may not be gender based anymore -- at least with regard to the proportion of bachelor's degree recipients in various science and technology fields who go on to earn Ph.D.s in those fields.

The paper compares this ratio for women and men over decades of cohorts in physical science, technology, engineering and mathematics. These are the science and technology fields where, traditionally, women have lagged behind men. (The figures are more favorable to women in the biological sciences.)

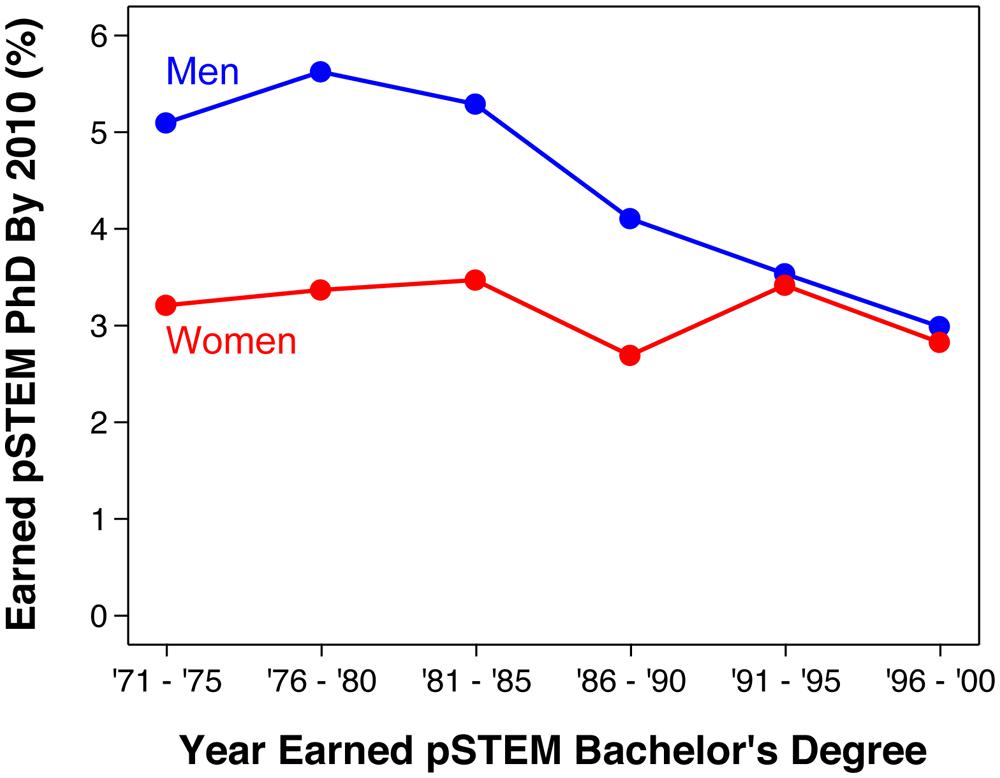

The researchers in the paper gathered data from two national longitudinal studies: the National Survey of College Graduates and the Survey of Doctorate Recipients. They found that, in the 1970s, men who earned bachelor's degrees in the fields studied were 1.6 to 1.7 times more likely than women to go on to earn a Ph.D. With more men than women earning bachelor's degrees to start with, this "leaky pipeline" contributed to fields in academic science where women were scarce.

But by the 1990s, and continuing on, the male and female cohorts earning bachelor's degrees in these fields were equally likely to go on to earn a Ph.D. While the percentages of all bachelor's graduates going on to earn a Ph.D. were going down, there was no gender gap any more.

The paper cautions that some of those in the last cohorts may yet earn Ph.D.s, so the figures for those cohorts (when the 2010 deadline is removed) may go up a bit. But to date, there is no indication that those changes will differ for male and female students.

The authors of the paper are David Miller, an advanced doctoral student in psychology at Northwestern University, and Jonathan Wai, a research scientist at the Duke University Talent Identification Program. Northwestern's news release on the findings pointed to the potential for this study to challenge conventional wisdom about women in science. The headline on the release: "Think again about gender gap in science."

In an interview, Miller was more cautious. He noted that there were differences among disciplines. In the physical sciences, for example, the gap between men and women was narrowed by a greater share of women completing Ph.D.s, while in computer science, the gap narrowed because fewer men were earning Ph.D.s.

He also said it was important to consider factors that may have little to do with the relative inclusiveness of various science disciplines. For example, he said that in fields such as computer science, the time period covered included years in which lucrative job opportunities existed for men and women with proven expertise but without Ph.D.s. So the reasons people didn't finish doctorates may have had nothing to do with gender. Others may have been scared off by reports of the poor academic job market.

Miller said that it was the case, however, that whatever factors were influencing the decision to complete a science or technology doctorate were, in aggregate, playing out the same way for men and women.

While the decision to get a Ph.D. is crucial to the pipeline in academic science, Miller said there are plenty of other issues that may be gender related and deserve continued attention. For instance, he noted (as does the paper) a recent drop in the number of women in science assistant professor positions (after several decades of slow but steady increases).

And Miller stressed that the positive findings about the leaky pipeline to the Ph.D. should not be read as a call to end the numerous programs colleges and universities have created to encourage women in science and technology fields. He said that those programs were making real progress and identifying scientific talent that might otherwise be overlooked.

Sue V. Rosser, provost of San Francisco State University and author of Breaking Into the Lab: Engineering Progress for Women in Science, said via e-mail that she was skeptical that the results reflected progress for women. "The major finding of the study is the 'leakage' or loss of men. It's not so much that women are leaking less; in fact, it's pretty constant. It's just that the [number of] men receiving STEM Ph.D.s [has] decreased."

Mary Ann Mason, codirector of the Center, Economics and Family Security at the University of California at Berkeley School of Law, said via e-mail that she saw the data as evidence of the continued problem of women not being provided the right environment to enter the professoriate. She said the emphasis on the study is on "the wrong trajectory," and that women who do finish Ph.D.s often feel that academic science is not a good career choice. And she said many women do finish their Ph.D.s and then leave academe. "They had decided the academy was not family friendly -- while in graduate school, or as postdocs, and they would not pursue a career in research science -- but they might be able to use the Ph.D. for something else," she said.