You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Following a year of upheaval concerning the size of the distance education market and who quantifies it, the Babson Survey Research Group's annual barometer of the students taking online courses contains few surprises.

The survey was never meant to make it this far, codirectors I. Elaine Allen and Jeff Seaman point out. What was intended as a “single snapshot” of the distance education market of the early 2000s is now in its 12th annual edition. During those years, the survey has tracked chief academic officers’ attitudes toward online learning and also attempted to quantify just how many students enrolled in at least one distance education course.

Last year, the Babson Group faced a crossroads. The National Center for Education Statistics began tracking distance education enrollment in the Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System, or IPEDS, and the results from fall 2012 -- the first batch of data collected by the federal government -- counted 1.6 million fewer students than the Babson survey's estimate. In response, Seaman said the federal government’s data were likely more accurate and that his survey would change to focus more on attitudes and trends.

This year’s report, released today, shows the result of that shift. The Babson Group now uses a combination of enrollment data from IPEDS reported by 4,891 colleges and universities (most recently from fall 2013) and additional survey responses from 2,807 of them (from fall 2014), but it is more interested in trends than totals.

“I would hope that we not quite obsolete yet, but getting there,” Seaman said in an interview. He described this year’s report as a “hybrid” between the enrollment-heavy editions of the past and future editions that will likely explore distance education strategies for different types of institutions. Relying on the federal government’s data on distance education students frees up room for more in-depth questions, he said.

The data from IPEDS is still not a perfect substitute. An analysis released last year -- included at the end of the Babson report -- found that some institutions incorrectly reported how many students they enroll in distance education courses.

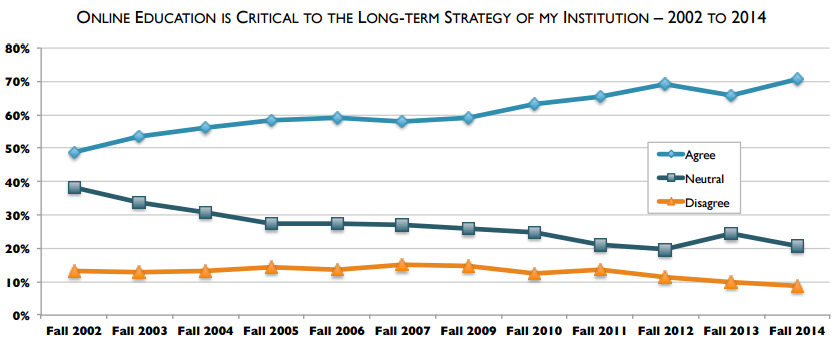

While the data sources have changed, this year’s results suggest a return to normalcy. Last year, the survey captured its first-ever dip in the number of academic officers who said online learning is “critical” to their institution’s long-term strategies. The data point was likely a blip rather than a trend, as the share has this year grown to an all-time high of 70.8 percent. At the same time, only 8.6 percent of respondents -- an all-time low -- say online learning is not an important factor in strategic planning.

The spike in negativity toward distance education last year came exclusively from academic officers at institutions with no online students. The finding baffled the researchers, who speculated that the drop could be a negative reaction to the hype surrounding massive open online courses. This year, the respondents appear to have changed their minds.

“We had this one group for one year who were more negative than they had been at any point in the past,” Seaman said. “For whatever reason they did it, it does not seem to have had a lasting impact.”

For-profit institutions are also behind the reversal from last year’s survey, according to the report. In the face of shrinking enrollments, the share of academic officers at those institutions who say distance education is important to their long-term strategies has jumped from 54.9 percent to 80.9 percent in one year. For-profit institutions shed about 63,000 students -- a 7.9 percent drop -- between the fall of 2012 and 2013, according to the IPEDS data, as more distance education students shifted away from that sector and toward public and private nonprofits. Those sectors grew by 160,000 distance education students, or 4.6 percent, and 86,000 students, or 12.6 percent, respectively.

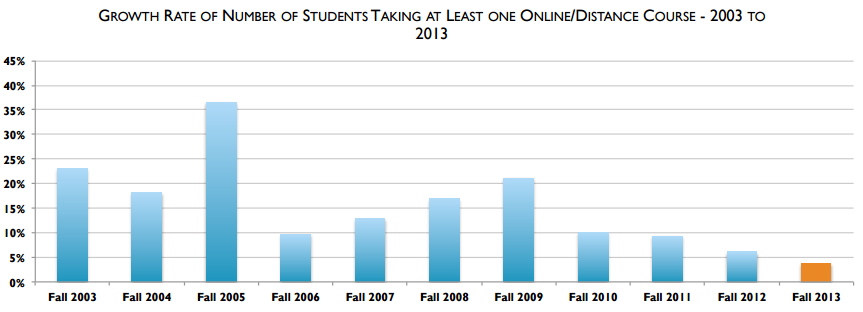

Across all of higher education, the growth from 2012 to 2013 in the number of students taking at least one online course -- pegged at 3.7 percent for a total of 5.2 million students -- is the smallest year-to-year increase since the inception of the survey. The growth still outpaces overall enrollments, which during the same period grew by 1.2 percent.

There are still significant barriers for institutions interested in offering distance education courses, however. Most concerning to academic officers is the effort -- from training faculty members to investing in the right technology -- needed to launch the programs; 78 percent of respondents described it as an important barrier.

Student retention is also a growing concern. In 2004, only 27.2 percent of respondents said it is more difficult to retain students studying online than those on campus, but that share is now up to 44.6 percent.

Seaman attributed the growth to forces outside higher education -- activists, families and politicians among them -- paying more attention to student outcomes and college completion. “For a lot of people, it’s probably just increased awareness,” he said. “There’s nobody out there saying something’s fundamentally changed.”

There is also the nagging concern about the quality of a fully online education -- a finding replicated by other research (including by Inside Higher Ed). Only about a quarter of respondents, or 27.6 percent, said faculty members at their institutions “accept the value and legitimacy of online education." The figure has hovered between 25 and 35 percent since fall 2002.

“It’s the most stubborn metric we’ve ever seen,” Seaman said. “The level of distrust by faculty members toward online has not changed substantially in over a decade.”

Interest in MOOCs, contrastingly, has not seen similar stability. Over the last two years, slightly more than half of respondents said they were undecided about whether they would offer a MOOC. Many of those respondents have now decided against, growing the share of institutions with no plans to offer a MOOC from 33 percent last year to 46.5 percent this year. Only 16.3 percent of academic officers now see MOOCs as a sustainable way of offering online courses, and 27.9 percent say they are important for institutions to learn about online pedagogy, down from 28.3 percent and 49.8 percent, respectively, in 2012.