You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

When it comes to first-year writing courses, how many sections are too many for one instructor to teach? Full-time, non-tenure-track faculty members at Arizona State University say five per semester, and they’re protesting their department’s plan to increase their teaching load to that number (up from four) each term, starting next fall. They say they’re worried the service work they’ll give up in exchange for the extra course won’t be taken up by tenure-line faculty, and that they won’t be able to give needy students the same level of attention.

In effect, the university has just increased instructors' teaching workload by 25 percent, without offering an extra dollar for the effort.

Faculty advocates agree that the planned course load is too much, and that it’s another example of an institution asking some of its most vulnerable faculty members to do more with less.

Arizona State, meanwhile, says the change is necessary to address a budget shortfall.

“This is bad idea because, No. 1, instructors already do a ton of work,” said a long-term instructor of first-year writing at Arizona State who moderates a website and petition protesting the university’s plan. “We also provide valuable service to the [English] department and the writing program, which is one of the largest in the nation.”

The instructor, who asked that her name not be used due to concerns about job security, added: “Further disenfranchising faculty from the department and the university makes this one a hard sell.”

Last week, all 60 instructors – meaning full-time, non-tenure-track professors – in Arizona State’s English department received an email from their chair, Mark Lussier, inviting them to a meeting tomorrow to discuss “the financial situation within the department and the need to move to a five-five teaching load beginning in the next academic year.”

Currently, instructors teach four courses each in the fall and spring semesters, with 25 students in each class. The cap used to be 19 students but was raised several years ago, also in response to budget concerns. Faculty members say that teaching even 100 students – many of whom speak English as a second language and need extra help – is trying, given that Arizona State’s curriculum is process-oriented, requiring lots of student drafts and feedback. It also stresses writing across various media, including multiple digital platforms.

Even now, instructor loads and class sizes exceed the caps recommended by professional organizations. It is unusual for four-year college instructors to teach five sections of a course.

Lussier added: “This does not make me happy, but given the budgetary constraints under which we operate this change (which has already arrived in most locations across the university) will quite likely become necessary.”

The chair discussed the plan with a small group of instructors before sending his email. One of the instructors present at that meeting, who also did not want to be named, citing fears about job security, said the change was a cost-saving measure, in light of anticipated budget cuts. Rather than receiving extra pay for teaching additional courses, instructors will be expected to give up the service and professional development activities that currently make up 20 percent of their working time; tenure-line faculty members are supposed to take on some of those duties, but will be otherwise unaffected by the change.

Those instructors who currently teach a fifth course will cease to receive overload pay for doing so, even though many instructors take on that work because base pay is relatively low: $32,000 starting for hires with a terminal degree.

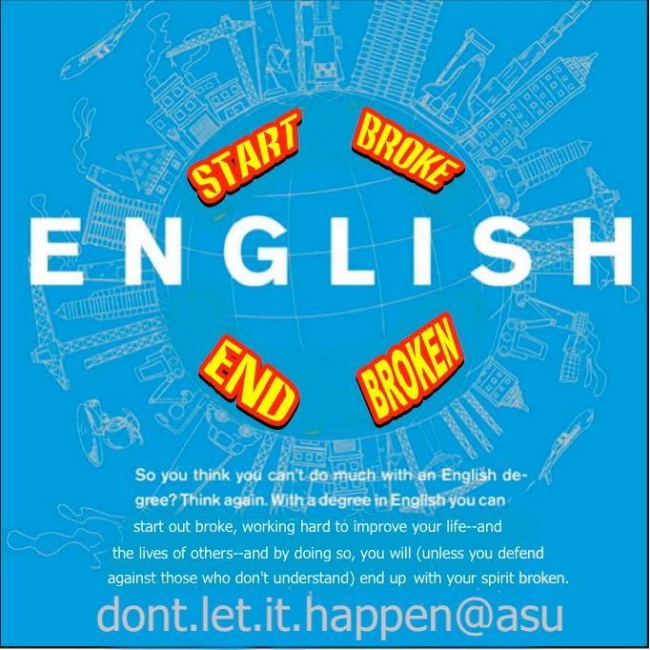

The moderator of the protest website, ASU Against 5/5, said she and about 50 percent of affected instructors are graduates of their department. They feel that the low pay and planned changes, made largely without their input, show the university’s “lack of commitment” to its alumni, she said. The sentiment is expressed on the ASU Against 5/5 Facebook page, whose profile graphic reads "English: Start Broke, End Broken."

The instructor also said she questioned any university policy that would encourage its faculty members to skip professional development and service tasks, and said she'd have to continue to do many of them anyway, uncompensated, to remain an effective teacher and receive positive reviews from students.

Shirley Rose, writing program director at Arizona State, said in an email that she shared "concerns that the service work that instructors currently do won’t — or can’t — be done by others. Instructors make up the membership of key committees for the ASU Writing Programs in the Department of English in the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences on the Tempe campus."

Rose said those committee are responsible for reviewing textbooks and developing text lists for courses, judging entries for a student writing competition, selecting peers for teaching awards, and planning an annual conference on teaching writing. "These activities won’t accomplish the same goals if they are carried out by others because they will mean something different," she said. "Engagement in these kinds of service activities is critically important, but they take time. With a 5/5 load, Instructors will not have time for them."

Lussier, the department chair, did not immediately respond to a request for comment.

Via email, an Arizona State spokeswoman said the university has "some people in instructor appointments whose assignments consist of teaching five courses per term."

"This has been the case in the past, is currently the case, and will be in the future," she said. "These are full-time, benefits-eligible positions. Generally, full-time instructors are not assigned service responsibilities. In this case, full-time instructors that had service responsibilities (previously 20 percent of their jobs) are having those service responsibilities taken over by others in the department so that the instructors can focus fully on teaching."

Stephanie Downie has been an English instructor since 2006. Between then and now, she’s seen a $500 professional development grant for instructors disappear and the student cap rise to 25 per section – which she said equates to instructors “already basically teaching a class for free.”

But with this new plan, she said, “The real issue becomes how much time do you actually have to work with students? We know what the best practices are and the most effective ways to teach students, and it all requires a lot of one-on-one time, and a lot of emails, and so on. … The larger the classes get and the more sections we’re given, the less we can do for our students.”

According to policy set by the Association of Departments of English, a subgroup of the Modern Language Association, college English teachers “should not teach more than three sections of composition per term,” and the number of students in each section should not exceed 15, “with no more than 20 students in any case.”

Put another way, the ADE says, “No English faculty member should teach more than 60 writing students a term; if students are developmental, the maximum should be 45.”

Doug Hesse, president-elect of the National Council of Teachers of English and professor and executive director of writing at the University of Denver, said his organization for many years recommended a maximum of 60 writing students per instructor per term. Although that language has been removed from the College Conference on Composition and Communication’s Principles for the Postsecondary Teaching of Writing statement, he said, it’s still good guidance. In any case, many large institutions that rely heavily on non-tenure-track instructors to teach first-year composition don’t exceed 80 students per instructor per term, he added. Many private, selective institutions aim for far fewer students; the University of Denver, for example, has a cap of 45 students, while Duke University’s maximum is 36.

Hesse said the Arizona State plan raised significant concerns about faculty working conditions, but said the “main cost to students is simply the amount of time that faculty can spend responding to writing and progress. It’s substantially curtailed.”

He compared effective writing pedagogy to “coaching" and said five sections isn't compatible with the quality of attention students should receive. Hesse also said eliminating a service requirement would mean eliminating the professional development that inevitably comes from service work, such as assessment projects. Keeping up with professional development in a field that's constantly evolving, with new digital modes of communication, genres and publishing practices, is especially important, he said.

"One of the job requirements of being a college professor, whether you're teaching first-year students or graduate students, is that you're continually developing as a professional," Hesse added. "What will happen is that a responsible teacher will try to make that happen, regardless. So it's an add-on, whether it's officially recognized by the contract or not."

Gary Rhoades, professor and director of the Center for the Study of Higher Education at the University of Arizona, said Arizona State’s anticipated budget shortfall likely stems from a massive lawsuit aimed at increasing funding to K-12 education in that state. That aside, he said, the state traditionally ranks as one of the worst in directing funding to higher education.

Unfortunately, he said, budget shortfalls often affect impact some of higher education’s most vulnerable employees: faculty off the tenure track, who are already earning “sub-middle class wages.”

“I think it’s fair to say instruction ought to be the last place you’re cutting, not the first,” he said.