You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Routine. Predictable. Orderly. They’re fine words, ones that convey a certain level of familiarity and comfort. But they don’t describe the ideal learning environment, at least, not for the four professors recognized today as some of the best college instructors in the country.

These veteran teachers of engineering, writing and paleontology opt for words like playful, flexible, even chaotic. There’s noise and movement. A rhythm that has taken years to refine.

The recipients of the 2014 U.S. Professors of the Year award are recognized for their success in teaching and commitment to working with undergraduate students.

“These forward-thinking instructors advocate learning by doing, putting their students in the driver’s seat of their own development,” said John Lippincott, president of the Council for Advancement and Support of Education (CASE).

The annual recognition of the U.S. Professors of the Year is organized by CASE and sponsored by the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching. Winners are selected from a pool of 400 nominees, and there are also 30 state winners plus one from the District of Columbia.

Nominees are judged on four criteria: impact on and involvement with undergraduates; scholarly approach to teaching and learning; contributions to undergraduate education in the institution, community and profession; and support from colleagues and current and former students.

Read more about each of the national winners below.

Laurie Grobman, Pennsylvania State University at Berks, for baccalaureate colleges

Laurie Grobman hit gold with a successful fusion of teaching, research and service. And it all fell into her lap in 2005.

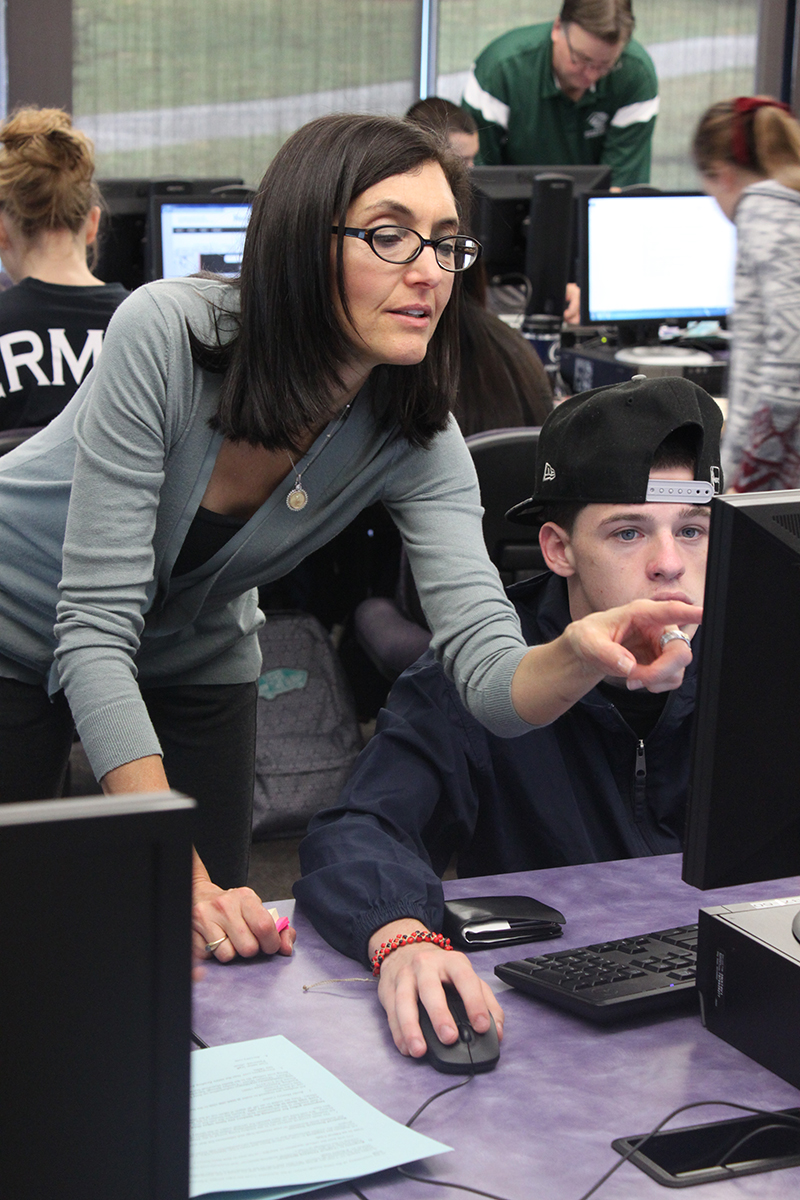

In the years since, Grobman (at right) has overseen several community-based research projects that bring attention to historically overlooked groups. Her classes have worked with the Central Pennsylvania African American Museum, Centro Hispano and the Jewish Federation of Reading.

In doing so, students learn about issues of social justice and multiculturalism through interviews with local historians and by researching old photographs and newspaper archives. They examine not only how power shapes history, but the role of language and rhetoric within that narrative.

Grobman also founded the Center for Service Learning and Community-Based Research at the university and has served as the editor of two journals for scholarly undergraduate writing.

Her main goal across all her courses, she said, is to get students to understand that race, class and gender are more complex than they realize.

“No matter what we’re studying or from which angle we’re studying it, those things all intersect,” she said.

Her students are working now on a history for the Olivet Boys and Girls Club of Reading and Berks County. The club was founded in 1898, but her students are learning that more than 100 years later, some of the city’s pressing issues are the same.

“Even though the demographics have changed, the issues remain: poverty and families who work and can’t be home to watch their children after school.”

Grobman’s favorite classes are the ones where she takes on a supporting role. Students are in the midst of their own research, sorting through archives and learning from guests from the community.

She knows academic research doesn’t excite every student. But she thinks the opportunity to leave behind a legacy with these projects has a unique way of sparking their interest.

“What they write, they have control over what gets preserved and what gets shared,” she said. “They’re in charge of shaping the stories.”

Patricia Kelley, University of North Carolina at Wilmington, for master’s universities and colleges

Patricia Kelley fell in love with dinosaurs when she was 7. She turned to math in college before the lure of paleontology drew her back in.

Teaching was never part of the picture. It sounded awful, actually.

But about halfway through her Ph.D. program, after some encouragement from her adviser to serve as a teaching assistant for a natural sciences course, something clicked.

That was more than 35 years ago. For the past 17, Kelley (at left) has been a professor of geology at the University of North Carolina at Wilmington.

Last week, to help students understand the evolution of a horse’s hoof, Kelley had a student volunteer slide on some large wooden shoes and run around the classroom, trying to escape from predators.

Students aren’t the only ones who will put on a silly sideshow to demonstrate a lesson, either. Kelley, for example, mimics how pterodactyls fly by tying a blanket to her wrists and ankles and running around the class.

“I try to create an atmosphere of play in the classroom, so the students are more willing to listen to me,” she said.

“I try to create an atmosphere of play in the classroom, so the students are more willing to listen to me,” she said.

That’s not to say that Kelley doesn’t teach serious topics. She’s helped write the Geological Society of America’s guide to teaching about evolution, as well as a book chapter about teaching controversial topics.

A lot of her students who aren’t science majors perceive evolution as threatening to their faith, she said. So before diving into the details of evolution, Kelley works to get to know each of her students and gain their trust.

“We talk a lot about what science is and how it’s different than their faith,” she said.

Kelley may be in a unique position to do so. As the wife of a Presbyterian minister, she teaches science during the week and Bible studies on Sundays.

She also helps lead faculty orientation sessions on applied learning and helped draft a university-wide plan to enhance student learning based on her knowledge from a decade of teaching a semester-long research project for undergraduates.

Students in her Invertebrate Paleontology course extract and identify fossils in sediment, test hypotheses, write their findings in the format of a professional journal entry and often present at geological conferences.

She enjoys seeing her students’ own evolution, “going from somebody who’s either hostile to or apathetic about science to someone who’s excited about it.”

Sheri Sheppard, Stanford University, for doctoral and research universities

When you pose a question to a sea of 20-year-old college students, well, sometimes all you hear is crickets.

To combat the tendency for silence, Sheri Sheppard (at right) employs a “think, pair, share” method, where students build up to confidence to share their thoughts by first talking through their ideas with a partner.

Sheppard, a professor of mechanical engineering at Stanford University, has made a variety of adaptations in her nearly 30 years of teaching to create an active learning environment in her introductory courses.

She started by using more demonstrations in class, showing how something responds to tension force with licorice. The layout of the room itself has changed, too, with the addition of movable tables and chairs divvied up into pods. Each pod is overseen by four graduate assistants with whom Sheppard co-teaches.

Her class is still evolving, too, and often at the direction of students. During the summers she oversees undergraduate research that’s usually based on an element of the course that a student found problematic. Last summer, she and a former student tackled homework, creating a professional survey to ask students how the experience could be improved.

To help students understand what their life as engineers would be like, Sheppard brings in professional engineers who are a few years older than the students and designs a series of labs so students see can bend, stretch and otherwise manipulate solid items

But understanding the work of an engineer goes beyond knowledge of designs and building. She wants her students to know how to design and build, but also to consider whether something should be built in the first place.

“Engineering isn’t just about physics and equations,” she said. “It’s this messiness and ambiguity in the real world.”

Engineering education is great at simplifying projects so students can learn the physics and see how tweaks change things, she said. But of course, the world isn’t that simple.

“I don’t think we’re as good at helping students learn to simplify the problems themselves.”

John Wadach, Monroe Community College, for community colleges

John Wadach has always been one to tinker and tweak and push his boundaries of comfort.

It’s with that affinity that the professor of engineering and physics has morphed engineering education over the past 30 years at Monroe Community College in Rochester, N.Y.

Gone is the early emphasis on theoretical courses, in which students were bogged down right off the bat by calculus and physics all the focus on the theoretical courses and calculus and physics. Instead, MCC’s engineering program is based heavily off a “design and build” curriculum that Wadach helped write. Students there learn basic engineering by actually doing it -- building prototypes and testing them.

For engineering departments, the first challenge is getting students to actually stay in engineering, Wadach said.

Departments around the country see a high number of students drop from the program early in their first year. That puts the onus on instructors to make the coursework exciting, so that the difficult coursework isn’t drudgery, but something students want to do.

Wadach puts as much emphasis on his teaching responsibilities outside of the classroom as inside.

He is working on a project supported by the National Science Foundation to create a concurrent model of engineering curriculum, where engineering students interact with their peers in fields they’ll encounter as professional engineers.

Wadach coordinates an annual engineering competition for high school students. He talks regularly with nearby universities to ensure MCC’s curriculum is up their standards to ease transfer for students.

He also advises two engineering student groups and recently organized an engineering and technology career fair for employers and students.

Wadach said he’s driven by the dedication of his students, who are often working full-time or raising a family. They’re busy, sometimes struggling to keep up, and still manage to come to class with a smile on their face, ready for work.

“Knowing the stories that the students bring here and the difficult lives a lot of them have,” he said. “I just really want to help them in any way I can.”