You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

After two years of hype about massive open online courses, academic leaders' expectations of all of online education have taken a small but remarkable step back.

That’s the main takeaway from "Grade Change: Tracking Online Education in the United States," an annual survey of more than 4,700 colleges and universities performed by the Babson Survey Research Group. The annual study was previously known as the Sloan Survey of Online Learning. The data, collected in partnership with the College Board, suggest online enrollment growth is slowing -- though not yet plateauing -- and that a divide is forming between institutions that offer online courses and degree programs and those that don’t.

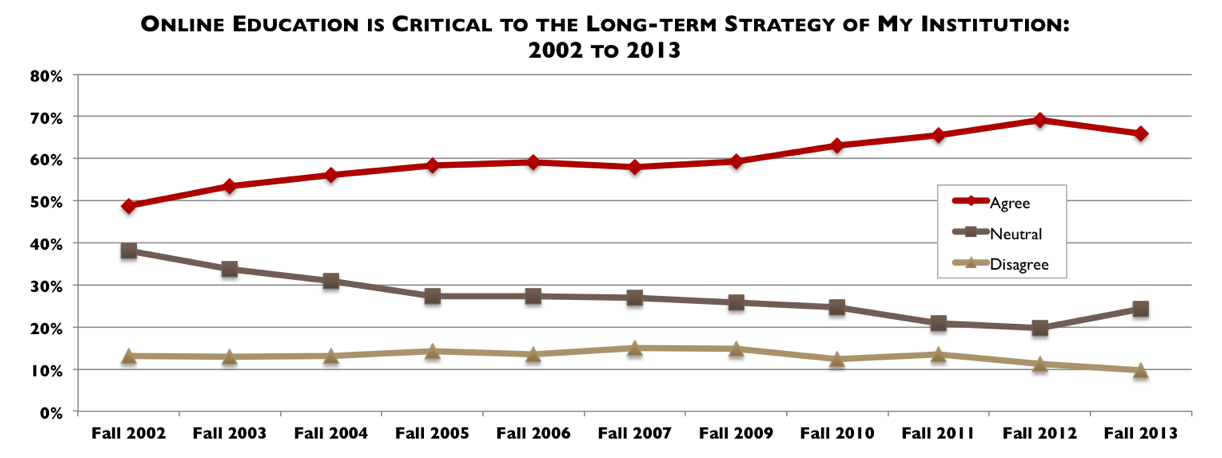

Since the report debuted in 2003, the number of academic officers who have said online education is a critical component of their long-term strategy has grown steadily, peaking at 69.1 percent in 2012. Last year, the number dropped to 65.9 percent, a decrease the report attributes entirely to officials at institutions without any online offerings. Among those institutions, the share of responses calling online education a critical component has plummeted from 32.9 percent in 2012 to 14.3 percent in 2013.

The drop has more to do with doubt that downright opposition to online education, however. Over all, institutions that said online education is not critical to their long-term strategy dropped to 9.7 percent, the lowest yet.

“I think its better to call them the ‘have’ and the ‘don’t want’ -- since the very beginning we have seen a group of institutions for which online was not a good fit (typically smaller schools and many of the traditional liberal arts institutions). This has not changed,” Jeff Seaman, co-director of the Babson Group, said in an email. “What has changed is they now have had a much more negative view about all aspects of online learning (its quality, its value, its role in higher ed, etc.).”

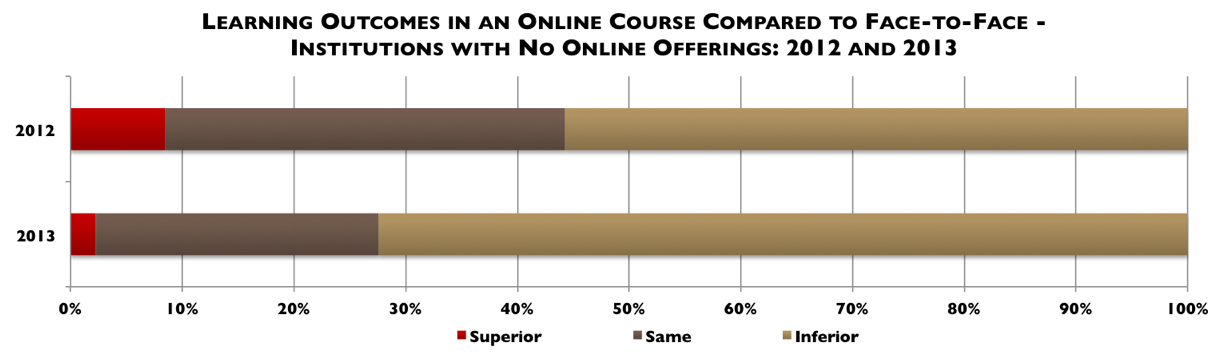

The pattern repeated itself when survey takers were asked to state their personal opinion on the learning outcomes of online courses. Among institutions with online offerings, the numbers held steady: 82.5 percent of respondents, most of them provosts and academic vice presidents, said outcomes are either superior to or the same as face-to-face courses -- virtually unchanged from 83 percent the year before. The same can’t be said for institutions with no online offerings, as 72.4 percent of respondents said online course results are inferior to face-to-face courses -- a jump of 16.6 percentage points.

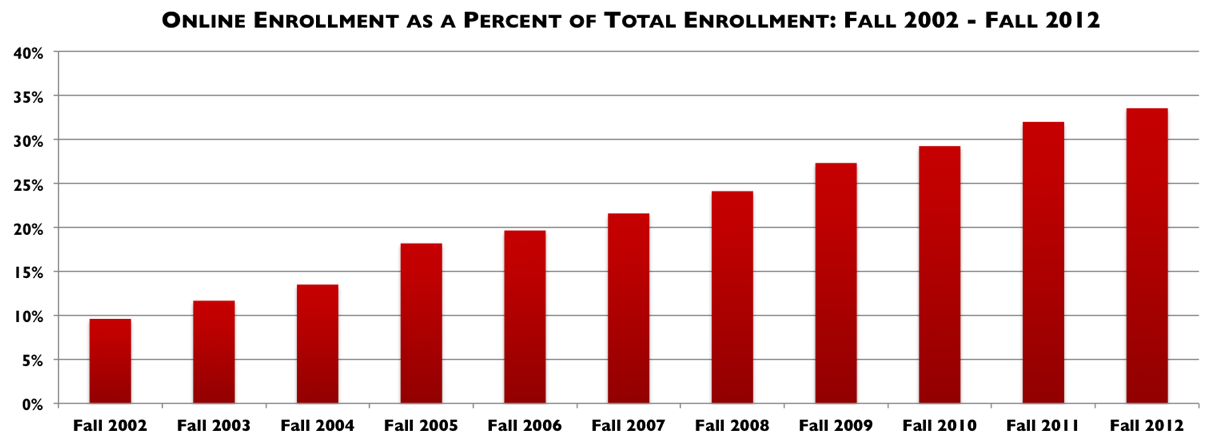

As large, public universities are more likely than smaller and private institutions to offer online courses and degrees, the growing skepticism among academic leaders at smaller institutions about online learning outcome does not yet appear to have affected the growth of the online student body. The report estimates about 412,000 more students enrolled in an online course in fall 2012 than the year before. With the total online enrollment reaching 7.1 million students -- an all-time high -- the share has for the first time reached one-third of the overall higher education student body.

The annual growth rate of 6.1 percent, meanwhile, suggests the numbers could plateau in a few years. Although it outpaces the 1.2 percent growth rate of students enrolled in higher education, the rate is the lowest ever recorded in the survey’s lifetime.

The drop is more than statistical noise, Seaman said. “There are always error bars around any point estimate (like the annual number), so this is always, at best, based on the estimated numbers from the reporting institutions.... Institutions may have biases in reporting their numbers, but these biases seem to be very consistent from year to year.”

Putting aside their personal opinions, most academic officers said they still see an online future for higher education. In the next five years, 9 out of 10 said it is likely a majority of students will enroll in at least one online course. But since 2011, when the Babson Group last asked respondents to look five years into the future, quality control has become an even more pressing issue.

In 2011, 36 percent of respondents said debates about the quality of online education would die down in the next five years. The proportion shrank to 32 percent last year, even as predictions about cost and access remained unchanged. In a separate question, 41 percent of academic officers also said retaining online students is more difficult than students in face-to-face courses.

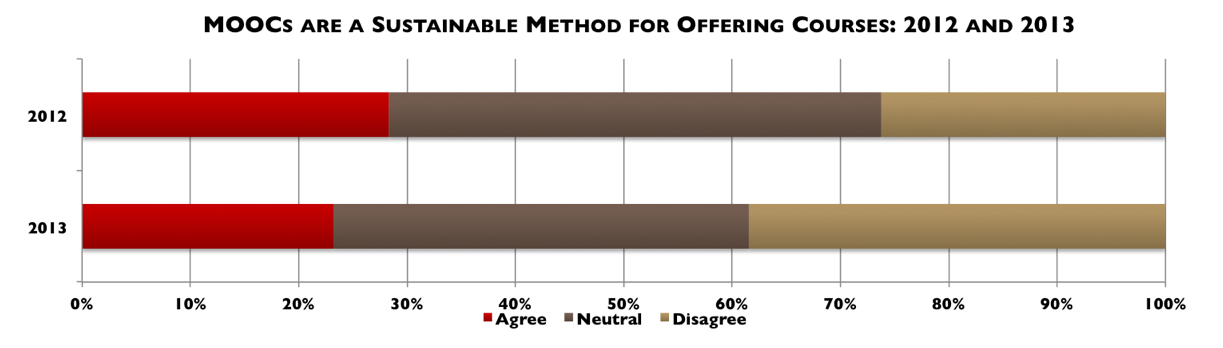

Questions about quality and retention have featured prominently in the ongoing debate about massive open online courses, which appears to have polarized the expectations surrounding MOOCs. In 2012, 46 percent of respondents neither agreed or disagreed that MOOCs presented a sustainable method of offering online courses, with the remaining respondents split almost evenly between the positive and negative sides. One year later, the share of respondents who disagree has grown to 39 percent, while those in agreement only make up 23 percent.

“Given that so many institutions are in the ‘undecided’ camp there is great potential for this to move in either direction,” Seaman wrote. “I think the real telling point will be in tracking the institutions that are experimenting with MOOCs for their specific objectives and their reporting of how well MOOCs are meeting those objectives.”

The shrinking number of MOOC supporters has been accompanied by an increase in respondents who say MOOCs will lead to confusion about postsecondary degrees. Most MOOCs do not offer academic credit, but many award students with a certificate for successfully completing the coursework. As a result, 64 percent of respondents now say the different kinds of credentials will be a source of confusion.

Still, a plurality of respondents -- or 44 percent -- said they believe MOOCs can serve as a useful exercise to learn about online pedagogy, even though the number has fallen from 50 percent from the year before.

Yet MOOCs remain a niche product. The survey found only 5 percent of the 2,831 responding institutions offer MOOCs, while 9.3 percent are in the planning stages. The remaining four out of five institutions were either undecided or had no plans to develop one.

“So far, it appears that MOOCs remain in the experimental category for most institutions -- without a compelling business model emerging,” he wrote. “In order for a much larger adoption to occur, there will need to be a strong case made for institutions with much more limited resources -- where the business case for the investment has to be clear.”