You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Cooper Union

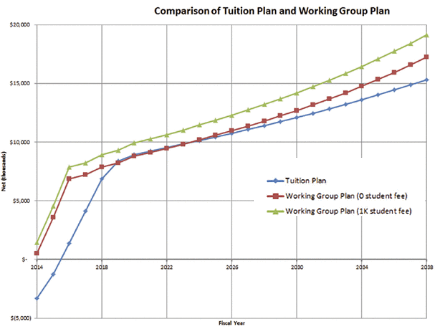

Eight months after Cooper Union administrators said there was no way to avoid charging tuition, a panel says there is. But some disagree.

Officials at the free university, which receives much of its money by owning the deed to the Chrysler Building, agreed to create the panel and take part in a “good faith effort” to rethink the administration's highly controversial tuition plan. That helped end a two-month student occupation of the president’s office.

Now, an 18-member panel of alumni, administrators, faculty, students and trustees released a report that says the university can not only avoid financial ruin but actually end up better off without charging tuition.

But a group of three administrators and a trustee who were part of the group disagree. They are now circulating a “minority report” that attempts to blow a hole in the larger group’s work. This minority maintains tuition is the only way to save Cooper Union.

Their minority report, which the university declined to release but which nevertheless became public this week, suggests the university’s staff and faculty are stretched thin. The minority report said attempts to cut the university workforce to save money, as the majority proposes, would be ill-advised. The university, for instance, often scrambles to find “a warm teaching body” to put in its classrooms, according to the minority.

The Board of Trustees plans to study the majority's proposal and meet in mid-January to decided if the alternative plan is realistic enough to avoid charging tuition. The respectful tone with which trustees have mentioned the report has encouraged those opposed to tuition, but the minority report suggests that avoiding charges may be quite difficult.

"There are no easy answers to Cooper’s financial difficulties,” university spokesman Justin Harmon said in an email. “If there were, the board would have pursued them and avoided the controversy that has manifested itself in our community over these past months."

One trustee who was not on the panel, Kevin Slavin, said in an internet posting that the trustees had “mostly productive” conversation about the alternative plan at a meeting earlier this month, but “not everyone supports the assumptions” within it.

“Ultimately, this is the question: what is the relative risk of each path?” Slavin wrote. “There being different types of risk. Financial risk is no bullshit, but nor is the risk of losing the very meaning of the institution.”

The financial risk to Cooper Union is stark: the university has about $230 million in debt and other liabilities and only about $100 million in assets, he said. The trustees spent 18 months reviewing the finances before they announced the plan to start charging tuition next fall, although there has been turnover on the board since then. Administrators have said that tuition could allow Cooper Union to improve, and to also provide plenty of financial aid for low-income students. But critics say that the no-tuition tradition is crucial in attracting students from all backgrounds -- and a key part of the spirit of the institution.

The panel's plan has three main sections – faculty, administration and real estate – designed to cut expenses and find sustainable cost reductions. All told, it attempts to find cost savings across the university rather than just asking students to pay.

“There are a lot of different constituents giving up something – not just one,” said Barry Drogin, an alumni member of the panel.

Some cuts would hit staff, like reductions in the number of security guards and fund-raising employees.

Others would hit the administration. The panel said the university could save $200,000 a year if it paid its president the median private college salary, rather than paying above the median in order to recruit a “star” president. The panel also said it does not need to pay future vice presidents, deans and other administrators much more than 150 percent of the national average salary for their positions.

“The college does not need to attract star executives at extreme salaries,” the report concluded.

The panel also suggested raising student fees and charging students who took more courses than the minimum number of credit hours needed to graduate.

Some of the cuts would hit faculty, like buyouts for full-time faculty or capping retirement benefits.

The minority report took most exception to this plan, which it argued would have the effect of increasing the university’s reliance on adjuncts. The minority report – written by the chief of staff and secretary to the board of trustees, a trustee, the dean of the engineering school and a senior official in the development office – bluntly said Cooper Union is too reliant on adjuncts already. Adjuncts teach about 40 percent of the university’s courses. Some are good, the minority wrote, but some are not.

“Many adjunct faculty bring professional expertise into the classroom,” they wrote. “Others are not up-to-date in their discipline or teaching practices.”

And adjuncts create scheduling problems because they have no obligation to be available at certain times and students are forced to overload on credits in a later semester to get back on track after they were closed out of classes due to scheduling overlaps. Adjuncts also cause chaos, the report suggests. "The beginning of each semester sometimes requires a scramble to hire a warm teaching body (or convince a full-time faculty member to teach an overload) to cover a course left open by an adjunct cancellation,” they wrote.

In an interview Wednesday, Drogin said he had not yet seen the minority report and dismissed it out of hand. He said it shouldn’t be considered a report at all because the goal of the panel was to come up with alternatives and this is not what the minority did at all.

Asked if he thought the administrators were trying to sabotage the majority’s work, Drogin replied, “It’s a shame there’s evil in the world.”

Drogin said even without the faculty changes, the panel's plan will save enough money and raise enough revenue to save Cooper Union and keep it tuition-free.

“I think we’re going to be able to do this,” he said. “I wouldn’t have wasted all my time on it if it wasn’t possible.”

He and others argue that the tuition plan has dangers that the administration is not accounting for, too. Namely, the tuition plan assumes that the high-caliber students attracted to a free Cooper Union will still want to come even though it’ll charge $20,000 a year for tuition. The university already charges about $1,800 a year in fees and about $15,000 a year for room and board.

Kerry Carnahan, an alumna and representative for Friends of Cooper Union, which opposes the tuition, called the report the first “honest, reasoned attempt to the save the mission of Cooper Union.”

“The general perception is that this a victory on two levels: that it saves the mission and it’s a better business plan,” she said.

A Cooper Union alumni organization has already endorsed the plan and other groups are expected to back the plan or at least not oppose key elements of it, including the faculty union. But it remains to be seen which side the trustees take.