You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

DUBAI -- During a discussion here Monday on international branch campuses, a panel of experts discussed a variety of challenges facing universities that set up branch campuses in other countries or engage in international partnerships. They discussed the economics of these ventures, shifting types of student demand, the potential of competition from massive open online courses and a variety of regulatory structures. But until asked during the question period, the panelists didn't say a word about the elephant in the room: differing commitments to academic freedom in the host countries for branch campuses and the Western democracies whose universities are setting up the branches.

The United Arab Emirates is home to numerous branch campuses of American and British universities, and many others are in nearby Qatar. So Dubai seemed a logical setting for Going Global, the annual gathering on international education sponsored by the British Council, and about 1,300 leaders of universities from around the world are gathering here for the discussions. While the universities setting up campuses here haven't asserted that the UAE is democratic, they have talked about their ability to operate campuses with academic freedom.

Ten days ago, that became more complicated. UAE authorities briefly detained a scholar from the London School of Economics and Political Science who flew here to attend an academic conference, and then sent him back home. The government then said it had acted because of the scholar's writings about Bahrain -- acknowledging that it blocked a professor from coming into the country because of his views. The scholar who was blocked from coming here -- Kristian Coates Ulrichsen -- has now published an article in Foreign Policy raising questions about the viability of Western universities working here.

"Denying me entry may have been a sovereign right, but it signifies that the gloves are off, and that the UAE currently is a deeply inimical place for the values that universities are supposed to uphold. As it becomes harder for academics and administrators to turn a blind eye to increasingly open abuses, proponents of academic engagement with the UAE will face a set of difficult choices as they try to balance the competing pressures of funding gaps and freedom of thought," wrote Ulrichsen.

So what did the panelists here at Going Global say? While the general theme of their earlier remarks was that quality branch programs are quite similar to those offered on home campuses, they said that there are differences with branches, and they referred frequently to "context" and "sensitivities."

Christopher Hill, director of graduate programs of the University of Nottingham's campus in Malaysia, said that there is a specific provision in his contract that says "that I can't say something that would be offensive to the government. It's written into my contract.... There are cultural sensitivities that you have to take into account."

Hill called the issue of academic freedom at branch campuses "a hugely complicated situation," but defended the compromises academics make abroad. "You are a guest in a country. There is a level of engagement one has to adhere to," he said. "Constraints on what you can say don't have to impact the quality of the material you are covering."

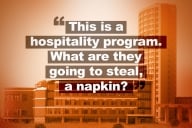

Nigel Banister, chief global officer of the business school of the University of Manchester, which has a campus in Dubai, said that "there has to be some sensitivity to culture." He elaborated that "certainly you'd look at case studies that are being used" so that they "are not going to be insensitive" to those in the UAE. He said that he thought the business focus of the campus might make it less likely to spur controversy.

Similarly, Ammar Kaka, head of the Dubai campus of Heriot-Watt University (whose main campus is in Scotland), said that his institution has not had any worries over faculty members running into trouble -- perhaps, he said, because most programs are in engineering and business.

Banister said it was important to also consider the gains for students in Manchester. He said that faculty members who spend time in Dubai learn a great deal about the Middle East, which they then share back in the U.K.

Hill also said that there were ethical issues raised by "a university entering a country in an attempt to change that country," saying that issues of freedom needed to be considered in a range of contexts.

And Tim Gore, director of global networks and communities for the University of London, said it was important to remember the positive impact Western universities have in countries without political freedoms. He noted that Nelson Mandela studied law at the University of London while imprisoned in apartheid-era South Africa. (Of course, that study was not via a branch campus.)

In private discussions after the session, attendees offered other insights on the issue. Several said that the UAE's refusal to admit a scholar from the London School of Economics made it hard to pretend that there wasn't an issue surrounding academic freedom. Others spoke of the reality that many Western universities see branch campuses as a way to diversify their revenue at a time of limited government support. And one senior official of a university in a Southeast Asian country that is currently seeking Western institutions to set up branches said that academics in the country understood that there were certain lines that one didn't cross for fear of funding being cut -- and that it was surprising that Western academics didn't realize this as well.

Questions Not Answered

While panelists did not immediately go to academic freedom issues, some did raise a series of ethical questions that are confronting universities with branch campuses -- and suggested that many universities aren't focusing on these issues.

Rozilini M. Fernandez-Chung, vice president of HELP University, in Malaysia, said that she believes "transnational education" (the term used at the session for branch campuses and other efforts in which a degree is awarded by a university based in a country other than where a student is enrolled) has "increased participation in education" in many developing nations. And she said that was a good thing.

But she said that she worries that transnational education is increasingly exacerbating economic and social divides in countries, rather than closing those divides. She noted that Western countries are charging tuition rates that, even if in some cases less than they charge at home, are beyond the reach of many. And as English has become the language of instruction in branch campuses, effectively this excludes those who haven't learned English from a young age. (However common English fluency is among the educated in much of the world, there are many countries where poor people aren't learning English, she noted.)

At the same time, Fernandez-Chung said that students in developing nations are starting to question whether branch campuses are truly the equivalent to the main campuses of Western universities -- and that they seem to want education that is as Western as possible. Students are asking questions such as "Will my teachers be British?" and "Will they be white?," she said. While the students asking the questions apparently aren't aware that Britain is more multicultural than it was in the past, their questions reflect a legitimate concern, Fernandez-Chung said.

Their view, she said: "If I want a British degree, I want to be taught by British people, not Malaysians employed by a British university."

She also touched on frustrations with quality assurance agencies. She said that some governments approach branch campuses like ostriches (ignoring them) while others take a "license to kill" approach (once you have a license, you can do whatever you want), while others take a "Roman" approach (when in Rome, do as the Romans do, so branches are judged by how closely they act like local institutions) and still others focus on making branch campus officials fill out the maximum number of forms.

These approaches are all flawed, she said, and they do not focus at all on improving the educational experience of students.

Several speakers here said that they viewed a commitment to maintain accreditation (or the equivalent) of home authorities for branch campuses as key to ensuring quality control and keeping the education comparable. But even that can be complicated. Kaka, the head of Heriot-Watt's Dubai campus, said that his university has all programs reviewed by appropriate bodies from Britain. But he's not sure that always helps. For certain kinds of engineering and design programs to be recognized, they must go through measures designed for professionals in Britain. Noting Heriot-Watt is starting a campus in Malaysia, he said that "central heating issues" (a requirement for British accreditation) are "not very relevant to students there."

MOOC Competition

Despite the various challenges discussed here, many of those attending are either trying to bolster or start branch campuses. Rahul Choudaha, director of research and advisory services at World Education Services, said that MOOCs may complicate those ambitions.

He noted that many MOOCs have enrolled large numbers of foreign students, and that MOOC providers are moving toward providing credit. It is true, Choudaha said, that some students who currently consider branch campuses or study abroad won't be lured away by MOOCs. This includes the very top students who have money (for whom the chance to study at elite Western universities is too great) and those whose primary motivation for study is a visa. But there are also many students who don't have much money and want career advancement. These students, he said, might well find MOOCs attractive, especially once credit is awarded.

Choudaha predicted that, in this environment, it will be harder for new branch campuses to be set up and for those that are not strong already to secure their positions. He suggested a leveling off of interest in branch campuses -- with "stronger campuses doing well."