You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

An associate degree is typically a cost-effective investment, for both students and state governments, yet community colleges continue to draw the short straw during budget season.

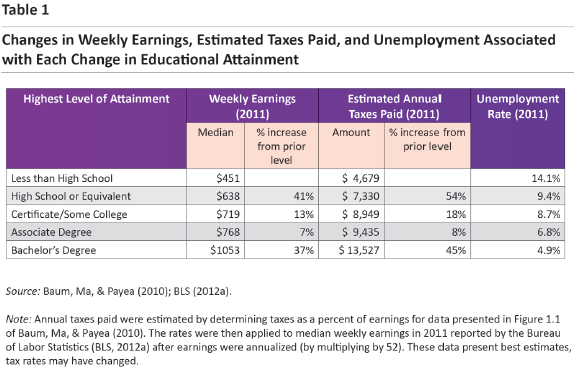

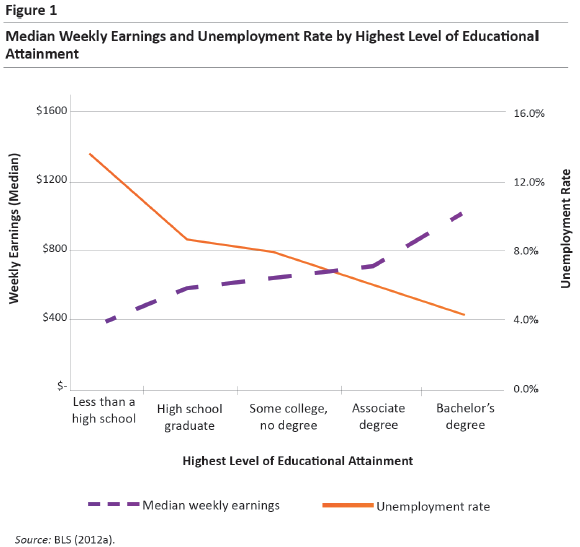

That's the bottom line of a newly released report from the American Association of Community Colleges, which tries to bolster the sector’s case for its efficient use of state funding by estimating community college graduates' annual tax payments. The estimates show that workers earn bigger paychecks and pay more in taxes for each level of education they have completed, from high school graduates to bachelor’s degree-holders.

For example, associate-degree holders paid an average of $9,435 in taxes in 2011 (including federal income, Social Security, Medicare, state and local income, sale and property taxes), according to the report, which was 8 percent more than what certificate holders or those with some college credits but no degree paid, and 29 percent more than the average tax payment of workers whose highest degree is a high school diploma or its equivalent.

“Each level of educational attainment matters,” said Christopher M. Mullin, the association’s program director for policy analysis and the report’s coauthor. “There are real earnings both for the individual and for the society.”

Recent research has shown the relatively strong value of two-year degrees and certificates in the workforce, and the report pulls together some of those findings. For example, fully one-quarter of bachelor's-degree holders earn less than workers with associate degrees. However, state governments invest less money per student in the community college sector than in public, four-year institutions. Community colleges enroll 43 percent of all undergraduate students, according to the report, but receive only 20 percent of state tax appropriations for higher education.

Some of that funding disparity is offset by local government support. But Mullin said local taxes do not go to community colleges in roughly 25 states, and that even in states where they do, the funding does not fully cover the shortfall in comparison to four-year institutions.

The association’s report, however, is careful to note that public universities have also had their budgets slashed on a per-student basis, and that the overall disinvestment in higher education is bad for the economy.

Community colleges are also doing the most to control their costs, according to the report. The sector is on the only one in higher education where operating budgets per student are smaller than they were a decade ago. Mullin said that frugality should be factored in by state lawmakers during budget season.

“We could a better job placing investments where we get a better return,” he said.

The report breaks down community colleges’ private and public economic returns into three different categories:

- The community college as launching pad, or as a starting point for students in their educational progression.

- The community college as a (re)launching pad, providing knowledge and skills to career-changers, displaced workers and lifelong learners.

- The community college as a local commitment, which serves the needs and demands of local communities.

“In order to continue to provide these benefits and fill in where other opportunities for education and training once stood,” the report concludes, “public investments in the education and training community colleges provide need to equalize and stabilize, if not increase.”