You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

College tuition went up again this year, but two reports released today by the College Board show that institutions are not increasing tuition at the same rates they were in recent years, a potential sign that the widespread concern about high prices is beginning to penetrate board rooms at colleges and universities.

The trend is particularly pronounced at private nonprofit universities, where moderated price increases, increased institutional aid, and larger federal expenditures on aid have actually dropped the average net tuition price -- what a family has to pay after grants and tax deductions are subtracted -- to less than it was five years ago in inflation-adjusted dollars.

The same cannot be said about public four-year institutions, a much larger sector in the higher education landscape. While the increase in published tuition prices this year (4.8 percent) is less than the average for the last five years (5.2 percent), the average net price, $2,910 a year, is more than double what it was two decades ago.

The findings of this year’s report further a trend recognized last year of a shifting burden of who pays for public higher education. States, facing decreased revenue, competing demands for resources, particularly in the form of pension and health care expenditures, and a political reluctance to increase revenues through taxation, have decreased per-student appropriations to higher education 25 percent in the past five years after adjusting for inflation.

In most states, public colleges and universities have responded by increasing tuition prices. But “through unusually large increases in Pell Grants, grants for veterans, and federal tax credits, the federal government increased its role in financing higher education, relieving the burden on students,” the report states.

That federal aid has now begun to level off and seems unlikely to keep pace with further growth. Cuts also appear to be on the horizon. “Part of the decrease [in net price] is due to the increased federal role in funding education, but that increase is also not a sustainable trend,” Sandy Baum, co-author of the report and an economist with the George Washington University School of Education, said in a press briefing on the report. “We cannot and will not continue to increase funding at the same rate. Net tuition, the burden on students, is rising, and we’re going to have to watch that trend carefully in the future.”

The reports and their authors suggest that if such cuts in federal aid do come to pass, and if states do not begin to reinvest in higher education, the amount that institutions expect students and their families to pay will increase dramatically, likely leading to higher debt burdens or more students deciding that college is not worth the investment.

A Net Gain?

The report highlights some dramatic differences between the public and private sectors.

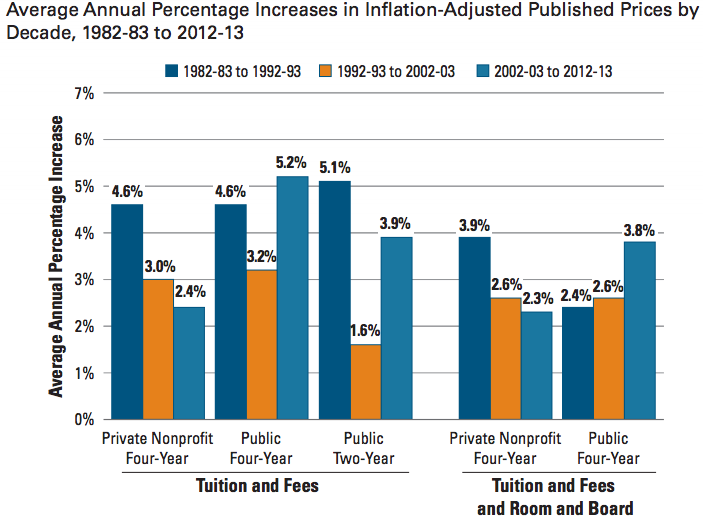

Among private nonprofit colleges, the average rate of increase in tuition prices has actually decreased each successive decade starting in 1982. That is not true for public four-year universities, where the past decade has seen the highest average rate of increase of the past three decades.

This year, public four-year and two-year institutions continued to see the largest percentage increases in published price, though the pure dollar amount increase was largest at private nonprofit institutions, as seen in the table below.

|

Sector |

Tuition and Fees 2012-13 |

Tuition and Fees 2011-12 |

$ Change |

% Change |

|

Public 2-year (in-state) |

$3,131 |

$2,959 |

$172 |

5.8% |

|

Public 4-year (in-state) |

$8,655 |

$8,256

|

$399

|

4.8%

|

|

Public 4-year (out of state) |

$21,706 |

$20,823 |

$883 |

4.2% |

|

Private Nonprofit 4-year |

$29,056 |

$27,883 |

$1,173 |

4.2% |

|

For-Profit |

$15,172 |

$14,737 |

$435 |

3.0% |

The 4.8 percent increase in published price for in-state students at public four-year institutions is the smallest increase those families have seen in 10 years, and comes after two years of average increases of more than 8 percent. Adjusting for inflation, it is still one of the smallest increases over that time period.

The average increase masks deep differences among states. In some states, such as Maryland and Ohio, the percentage increases from 2008 to 2012 have been less than 4 percent. In others, such as California and Arizona, the change in sticker price over the same time period has been more than 70 percent. The inflation-adjusted tuition price at Maine's two-year public colleges actually dropped 3 percent, while it more than doubled in California.

Aid programs have moderated some of this growth in tuition prices, but increases in other expenses, including room, board, books, supplies and transportation, have made college more costly for students in all sectors in the past year, as seen below.

|

Sector |

Total Charges 2012-13 |

Total Charges 2011-12 |

$ Change |

% Change |

|

Public 2-year (in-state) |

$10,550 |

$10,291 |

$259 |

2.5% |

|

Public 4-year (in-state) |

$17,860 |

$17,136 |

$724 |

4.2% |

|

Public 4-year (out of state) |

$30,911 |

$29,703 |

$1,208 |

4.1% |

|

Private Nonprofit 4-year |

$39,518 |

$37,971 |

$1,547 |

4.1% |

Several factors could explain why the increase in published tuition prices was lower this year than before. First, the rate of inflation was lower this year than it has been in most recent years. Second, colleges and universities might be responding to increased political and market pressures to moderate their increases. Recent surveys have suggested that students and their parents are weighting price more heavily in the college search process.

While the sticker prices tend to attract the most attention and generate the most headlines, and could potentially prevent students for applying to particular institutions, they are not a truly accurate measure of the cost of education. The College Board report finds that only about one-third of students pay the full sticker price, and some of those students receive some form of tax deduction.

Students at public four-year and two-year institutions received an average of $5,750 and $4,350, respectively, in grant aid and tax benefits to help pay for college, according to the report. And the gap between what colleges list as their price and what the average student pays after grant aid and tax reimbursements has grown wider as financial aid programs have played a larger role in paying for college.

While published prices for in-state students at public four-year institutions have doubled since 2008-9, the average cost after aid has increased only about 24 percent. The cost actually dropped almost $400 in 2008-9, when the federal government expanded its aid programs and institutions increased their own aid programs to respond to the economic downturn.

At two-year public institutions, the average amount of grant aid students receive actually fully covers the tuition price and helps students cover $1,220 of additional expenses.

The Loan Problem

Despite all the rhetoric (and countless anecdotes) about students with debt burdens exceeding $100,000, the report finds that “most students borrow responsibly,” said Megan McClean, policy director at the National Association of Student Financial Aid Administrators.

According to the report, only 2 percent of students who entered college in 2003-4 had more than $50,000 in cumulative debt. Forty-three percent of students took on no debt, and another 41 percent had less than $20,000 in cumulative debt. “Some students borrow more than they can manage, but it’s a small percentage of students,” Baum said.

For the first time in the past two decades, the total amounts distributed in grants and loans in the 2011-12 school year were actually less than the preceding year.

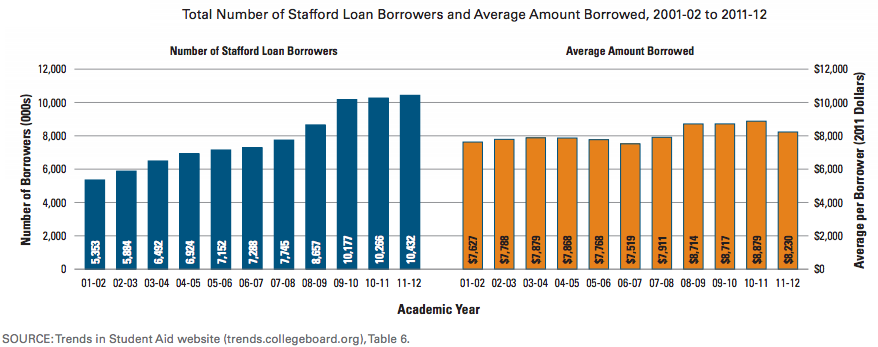

The increase in the overall amount of debt taken on by college-going students -- the oft-cited $1 trillion mark -- has been driven primarily by increases in enrollment and the number of students borrowing, the College Board report finds. Average federal loan amount per full-time student actually decreased slightly in recent years after a dramatic increase from 2007 to 2009.

The increase in the overall amount of debt taken on by college-going students -- the oft-cited $1 trillion mark -- has been driven primarily by increases in enrollment and the number of students borrowing, the College Board report finds. Average federal loan amount per full-time student actually decreased slightly in recent years after a dramatic increase from 2007 to 2009.

Moving Forward

Baum said that the price and cost of higher education are beginning to stabilize as the economy stabilizes. While most families continued to see their mean incomes decline, the top quintile saw their incomes increase between 2010 and 2011, which could signal the start of a turnaround. The unemployment rate has also decreased over the past 12 months. Such shifts could begin to increase the expected contribution of families to their children's educations.

Total undergraduate enrollment also saw small declines after several years of sharp increases.

But the looming problem, as noted in the report, is the potential for cuts in federal aid, which now account for 73 percent of all student aid. “Concern over federal budget deficits is growing, and while support for existing levels of student aid is strong, it is difficult to imagine continued growth in student aid programs that would compensate for future tuition increases to any significant extent,” the report states.