You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

As politicians, pundits and others continue a debate about the economic worth of a college degree, the National Technical Institute for the Deaf believes a unique database can give Congress an idea of what value, exactly, its credentials add.

The college for deaf and hard-of-hearing students, part of the Rochester Institute of Technology, has worked with the Social Security Administration to develop a data set unparalleled in American higher education, with information on 14,000 students who have applied to NTID since it opened in 1968. As a result, the college can track not only students who graduated, but those who were admitted and did not attend, those who dropped out, and those who were not admitted.

The college provides the students’ (or applicants’) Social Security numbers. The federal agency analyzes the data, so no one other than Social Security has access to information about specific, identifiable students. But the college can see financial outcomes, including earnings, and dependence on social welfare programs, for both graduates and non-graduates anonymously from the past four decades. It is a wealth of information that no other college has: Most data on graduates' salaries at other colleges comes from surveys, which are considered far less accurate and complete.

Few recent ideas in federal higher education policy have been as widely discussed -- and controversial -- as the idea of a database that would track students from childhood into college and, eventually, throughout their working lives.

Proponents of the idea argue that the database could better measure graduation rates for students who transfer across state lines. And it could evaluate the value of a college degree for students once they enter the working world, by linking students’ educational background with their employment rates and earnings. Still, the last effort to create a database, in 2008, failed after congressional Republicans and private colleges pushed back, arguing it would invade students’ privacy.

As the federal government calls on colleges to prove the economic worth of their degrees -- from the new rules requiring vocational programs to demonstrate that their graduates can pay off student loans to President Obama’s call to use financial aid to reward colleges that provide “good value” and punish those that do not -- calls for such a database are likely to intensify before the next renewal of the Higher Education Act, scheduled for next year. The National Technical Institute for the Deaf believes its data could be a model.

In some ways, the college, which offers mostly associate degrees in fields like computer technology and accounting, is a special case. Founded in 1965, it is one of only three non-military colleges to receive money directly from Congress for operations. This means that it must make a case for its continued support. It also made it easier for the college to partner with the Social Security Administration; staff from the administration co-authored a study on the results, published last year in the Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education.

“Congress has increasingly required that federal funding result in measurable economic return,” the college’s president, Gerard Buckley, said in e-mail interview. "Although NTID does not lobby Congress, this research has enabled us to provide lawmakers and decision-makers with empirical evidence that funding our institution results in significant fiscal payback.”

Among the findings: once their careers were established, graduates of the institute earned significantly more than non-graduates. Graduates were also far less likely to rely on Social Security programs for the disabled, suggesting a high degree of economic independence.

By age 50, bachelor’s degree-holders earned about $36,000 per year. Applicants who were admitted to the institute but did not attend earned less than $23,000 annually.

Adults aged 21 to 64 with severe difficulty hearing earn about $23,300 per year, according to the Census Bureau's American Community Survey.

.jpg)

Source: National Technical Institute for the Deaf

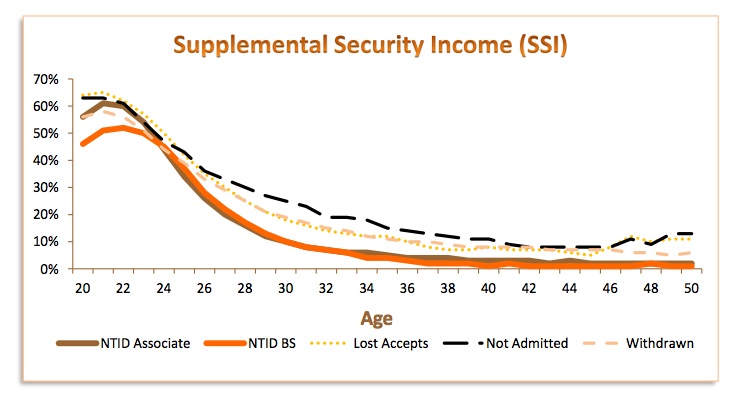

While those salaries are still low for college graduates overall, they are considered strong for deaf graduates, who might often face misunderstanding or bias in job searches. And the institute considers the numbers significant because they indicate that graduates can support themselves without help from the government. When students enrolled, more than three-quarters were receiving benefits through Supplemental Security Income, a government program that provides support for disabled adults and children who are unable to work. By age 30, 10 percent of students with a degree were still receiving SSI, compared to about 20 percent of dropouts and admitted students who did not attend and 25 percent of those who were not admitted.

Leaving the SSI rolls, for those who have received the benefits into adulthood, is highly unusual, said Richard Burkhauser, a researcher at Cornell who studies disability policy and has studied the NTID data.

Source: National Technical Institute for the Deaf

For Social Security disability benefits -- which are paid out to people who have worked and paid payroll taxes, but find themselves unable to work due to disability -- about 22 percent of graduates with a bachelor’s, and 27 percent of graduates with another degree received the benefits by age 50. For non-graduates, the numbers were higher: about 34 percent. Overall, about 25 percent of deaf adults ages 18 to 64 receive Social Security disability benefits.

The college mostly offers associate degrees, in fields like accounting and computer science, but students who complete an associate degree at NTID can go on to get a bachelor’s from RIT.

The results “unequivocally” demonstrate the value of a degree from the institute, NTID administrators said.

Data collection has continued -- the college just sent a new cohort to the Social Security Administration to be analyzed -- as has analysis of the previous results. Researchers are now looking more closely at the college’s admissions standards, trying to compare students with roughly equal academic track records to see the difference a degree makes. Students who just missed being admitted, and students with test scores in a similar range who did graduate, could be compared, for example, Burkhauser said. The college also recently obtained data on deaf students educated at other colleges, and will be using it for comparison as well.

It’s unclear whether other colleges could replicate NTID’s approach. The college’s agreement with the Social Security Administration, which does all analysis including personally identifiable information, is in part a result of its special status with Congress. Only two other non-military colleges, Gallaudet University, the liberal arts-focused university for deaf students, and Howard University, receive directly appropriated operating funds.

Still, there are hints that such data sets could be possible, if authorized by Congress. The federal government relies on loan repayment rates, including how payment amounts relate to graduates’ incomes, to evaluate vocational programs under the “gainful employment” rule. Social Security data will eventually be used as part of those metrics. The data is provided as part of an agreement between the Education Department and the Social Security Administration, and could -- at least in theory -- be expanded to other colleges as well.

But those new efforts wouldn’t necessarily have the years of historical data that Burkhauser said make NTID’s research so unique. “This is data that no other university in the country has,” he said. “It’s mind-boggling what we’ve been doing with it."