You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

A dozen more universities have signed partnerships with Coursera, a company that provides hosting services for massively open online courses (MOOCs), the company announced today. Coursera’s new partners include the University of Virginia, whose highly publicized administrative ballyhoo last month made it the epicenter of the debate over how traditional universities should adapt to the rise of online education in general and MOOCs in particular.

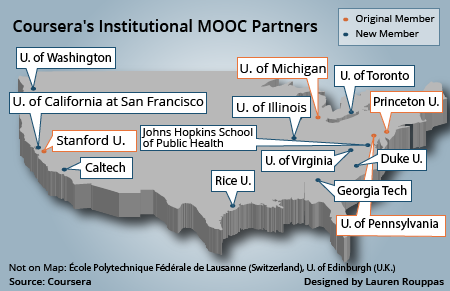

In addition to U.Va., Coursera will also be serving as a platform for open online courses from the California Institute of Technology, Duke University, École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne (in Switzerland), Georgia Institute of Technology, Johns Hopkins University, Rice University, and the Universities of California at San Francisco, Edinburgh (U.K.), Illinois, Toronto and Washington.

Sticking to its theme of hosting “elite” MOOCs, Coursera plans to adapt the most highly reputed parts of each new partner’s curriculum -- medicine and public health courses from UCSF and Johns Hopkins, biology and life sciences courses from Duke, business and software courses from Washington, and so on. Those institutions join Princeton University, Stanford University, and the University of Michigan and University of Pennsylvania as Coursera partners.

“We’re trying to work with top universities with high academic standards and good teaching,” says Andrew Ng, who co-founded Coursera this year with former Stanford colleague Daphne Koller.

Repeating what has become a common refrain among traditional institutions, officials at several of the universities said they are hoping that experimenting with MOOCs will help their professors develop teaching techniques that they can use to improve their traditional classroom-based courses. These could include replacing some lectures with online modules that students can work through outside the classroom in hope of freeing up class time for more interactive projects and exercises -- an increasingly popular method known as “flipping the classroom.”

“It looked like, in a sense, an accelerator for some of the things we were likely to be doing and the things we knew were going to want to be doing,” says Peter Lange, the provost at Duke.

“We think we can join with these other universities on collectively learning from this,” says Philip Zelikow, the associate dean for graduate academic programs at Virginia. “In a way it’s a large R&D project, where we get to participate with a lot of universities that we regard as our peers.”

Already the largest platform in the still-young field of MOOC providers, Coursera could increase its reach by a factor of four with the new partnerships. After initially forming in the shadows of fellow MOOC providers Udacity, which got more press, and edX, which got more money, Coursera has grown much more quickly than its peers. It now has 16 institutional partners, with more than 150 open courses in the works.

While Udacity has elected to team up with individual professors and edX has not announced any partners beyond M.I.T. and Harvard University, Coursera has attracted partners based on selling itself as a “humble hosting platform” upon which top-tier traditional universities, some of which might still be dubious of transposing entire degree programs to the Web, can extend their brands online in an innovative way. The two professor-entrepreneurs had to court their earliest clients; now universities are courting them.

“One thing we’re seeing, when we speak with universities, is many university leaderships are getting asked the question, ‘What is your online strategy?’ ” says Ng. “… I think, fortunately, Coursera offers a pretty compelling answer to that.”

Who’s Afraid of Virginia MOOCs?

Having a compelling answer to the online question seems more necessary than ever, even for the heads of institutions that have been relatively well-insulated from the upheaval that the medium has caused in higher education.

Just ask Teresa Sullivan, the president at Virginia. Jeff Nuechterlein, a venture capitalist and Virginia alumnus, believed that Sullivan possessed merely a “pedestrian” answer to the online question “in light of what Stanford and others had announced.” Nuechterlein said as much last month in an e-mail to Mark Kington, the vice rector of Virginia’s Board of Visitors, that has since become public. The university’s governing body seemed to agree. It tried ousting Sullivan last month, citing “philosophical differences” that appeared to include the pace at which the university should adapt to the rise of online education. (Sullivan has since been reinstated.)

Further e-mails among top board members suggested that the board was paying particularly close attention to MOOCs, which had enjoyed a great deal of media hype since Coursera, Udacity and edX had arrived on the scene.

Ironically, at the time the board was plotting the Sullivan ouster, delegations of deans and faculty members from Virginia’s undergraduate college of arts and sciences and its graduate school of business were both talking to Coursera about collaborations that would put the university on the crest of the MOOC wave, along with Stanford and the others.

Several days before the board asked Sullivan to resign, a large delegation from the university’s Darden School of Business -- the dean, several staffers, and 10 members of the business faculty -- met with the Coursera founders in their Mountain View, Calif., office, according to Carolyn Wood, a U.Va. spokeswoman.

“The board was not aware of these ongoing discussions,” Wood told Inside Higher Ed in an e-mail. But Sullivan was “almost certainly” in the loop prior to the board’s attempt to remove her, according to Wood.

Meredith Jung-En Woo, dean of the college of arts and sciences, also raised the possibility of aligning with Coursera in early June during a professional retreat with her fellow deans, according to Zelikow, the associate dean for graduate academic programs.

At the retreat, Zelikow had been tasked with contacting Coursera. Then the crisis hit. When the board’s e-mails revealed an interest in having Virginia get involved with the burgeoning MOOC movement, it “amused us a little bit since we had quietly begun working on this stuff in our own way,” says Zelikow.

While several factions within the university were contemplating MOOCs before last month's debacle put Virginia's online strategy under a microscope, "I think it was entirely reasonable to think that the activities of President Sullivan and the board accelerated these activities,” says J. Milton Adams, Virginia's vice provost for academic programs.

Virginia is planning four MOOCs through Coursera -- a history course, a philosophy course, a physical science course, and a two-part business and management course. Zelikow, who is also a history professor at the university, will be teaching The Modern World: Global History Since 1760. (This paragraph has been updated.)

“I am pleased to have the University partner with Coursera because we have a shared understanding of the importance of strong teaching and of learning outcomes,” said Sullivan in a statement.

“There are still many unknowns for us to study concerning the long-term impact of this form of online teaching,” she added later in the statement, “but it's critical for U.Va. to be in on the ground floor so that we can learn along with our peers what the future holds.”

For the latest technology news and opinion from Inside Higher Ed, follow @IHEtech on Twitter.