You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

The Consortium for Online Humanities Instruction is one of the largest-scale experiments (at least if you measure scale by the number of institutions involved, rather than enrollments) in online postsecondary learning. Over the course of several years, 42 member institutions of the Council of Independent Colleges built a set of upper-level online and hybrid humanities courses to be shared by their peers.

The goals: help them learn how to cost-effectively develop and launch high-quality online humanities classes, and give learners access to courses not available in their own curricula.

Along the way the project -- funded by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, and analyzed by Ithaka S+R -- committed to sharing its results with its fellow colleges and others in higher education.

The latest (and last) of a series of reports about the consortium was released this week, summarizing the lessons learned for the colleges and for the participating instructors and students.

Many of the findings may be unsurprising to professors or administrators who track digital learning issues closely -- but they were revelations for some people at these institutions that had largely stayed on the online ed sidelines before this project.

Student participation broadened. Many students said they appreciated the online courses because of the flexibility of scheduling they allowed. Some students said they were more comfortable participating in in-class discussions online than they are in traditional classrooms. As Bryon Grigsby, president of Moravian College, said at a workshop of consortium participants, "I quickly realized that the technology created a kind of access that we had not had before. It enabled the 10-second thinkers in the class to be able to get into the conversation on a threaded discussion where previously they had been silenced by the two-second thinkers who dominated a face-to-face class."

Some number of students at these primarily residential campuses likened the online courses to a "study away" opportunity. "For example, one student enrolled in a women's college found herself in a coeducational class for the first time, and considered it enriching and enlightening," the report said.

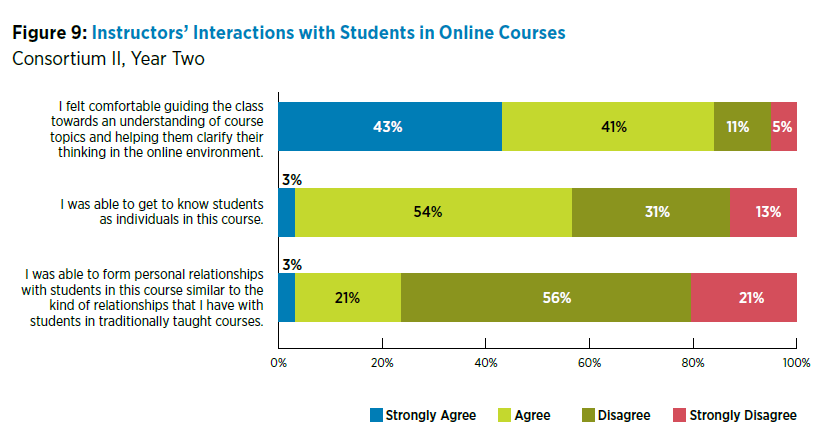

Faculty miss personal interaction. While numerous instructors said they built deeper relationships with "the quieter, more reticent students," many more said they did not form personal relationships with students like those that are common in person at their small institutions, as seen in the graphic below.

A stimulus for improved teaching. "Nearly all the faculty members reported that teaching online courses had helped them become better instructors in their face-to-face courses as well," the report stated. Numerous professors said that teaching increasingly seems like a "team effort" rather than a solo activity, including colleagues not just from their own institutions but from their peer colleges, as well as course designers, librarians and others.

Efficiency but not cost cutting. Professors found that creating and teaching online courses took more time, not less, and as a general rule, the consortium's members did not find that their hoped-for cost savings materialized. They did find, though, that the course-sharing arrangement expanded their higher-level offerings in disciplines with small departments. "Course sharing can help each institution offer specialized courses less frequently but more efficiently, on a more predictable rotation, and with specialized courses from other institutions rounding out a shared roster of offerings," the report stated.