You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Uri Treisman

League for Innovation

NEW YORK CITY -- More than 1,000 community college faculty members and administrators converged here this week for the League for Innovation in the Community College's 2019 Innovations Conference. While the annual convening is overwhelmingly attended by people from two-year colleges and explores some issues most relevant to those institutions, such as career and technical education, much of the content is relevant to anyone interested in student success, instructional innovation and institutional change. In other words, many of you.

Below are some highlights from the event.

***

As Uri Treisman told the story Monday, he had sneaked into a recent $5,000-a-head speech ("Who's going to stop a 72-year-old guy in a nice suit?" he said) but grew increasingly aggravated as the speaker told the crowd of trustees that the "problem with American higher education is that there's not enough innovation."

Treisman raised his hand to respond but was told that questions could be submitted only on paper and would be answered when the speaker had finished. Treisman persisted with his hand up, and eventually the speaker relented. "Do you have a question?"

"Yes, I do. Have you actually visited any colleges on any of the inner planets?" he recounted saying, to roars of laughter.

If the conference's attendees thought this was a lead-in to a Pollyannaish defense against the common critique that higher education never changes, Treisman had other ideas.

Higher education's problem is "not too little innovation," the University of Texas mathematician and educational equity champion continued. That's especially true of community colleges, which must constantly try new things because money is tight and "we're constantly trying to fix things."

The actual problem is "too much innovation that doesn't scale," he continued. "It's one of each innovation" -- one that a trustee asks for, one sought by a community member, one that responds to a foundation's grant. "It's innovation as ornamentation."

The way the idea of scale is most often considered in higher education contexts is by starting with pilot projects and expecting to expand them. But "we all know that pilots don’t scale," Treisman said.

The alternative way to get to scale is by working through systems -- which is difficult when higher education is made up of thousands of individual institutions that, while sometimes part of districts or systems that have some authority over them, operate largely independently.

But every once in a while something comes along to show that a good idea, a major change, can scale into something systemic -- and Treisman has been a major driver in one such phenomenon unfolding now: the steady abandonment of developmental mathematics education in favor of corequisite math courses that are relevant to students' interests.

Remedial math courses were "burial grounds for the aspirations of legions of students who trusted us to help them get upward mobility," Treisman told the community college officials at the Innovations meeting, failing the vast majority of students who took them. After experimentation that has produced "enormous evidence" that having students take credit-bearing math courses with significant support, the corequisite approach is "spreading through legislation in about 20 states," executive orders and adoption by large systems of community colleges.

The effort is not complete: "It will take another five years of work, but it’s going to happen," Treisman said.

What can be learned from the broad spread of this approach -- the kind of scaling that many argue is difficult if not impossible in higher education?

"This is a system problem -- we had to work both on our campuses and with the institutions that share the same students," he said.

So many aspects have to change to bring about a fundamental shift like this. Treisman laid them out:

- Support must be built around the students. Previously, a math instructor might tell an underprepared student who was behind in algebra to go get tutoring. "If you’re three days behind, you don’t need the tutoring center. You need to go to Lourdes for a faith healer," Treisman said. Instead, the tutors must be in the classrooms.

- Good institutional research is key. "You can't use improvement science if you don't have history. Most of our institutions don’t have the capacity to keep track of what we’ve done in the past. IR must be redesigned so it is actually a resource for improvement."

- The faculty must drive the work.

- Deans and other campus administrators must be supportive. "It takes administrative energy and muscle to coordinate and support the faculty work, and to think through the budgetary resource allocations and trade-offs that are necessary."

- Four-year colleges must provide transfer credit for the redesigned math courses -- and not just as gen ed, but "into the students' actual programs of study."

- Presidents, boards and professional societies must provide cultural reinforcement.

All of the institutional and system redesign that colleges are engaged in to remake how they serve academically underprepared students has the potential, Treisman argued, to better address a problem on which higher education has made stunningly little progress: providing equitable access.

"For 30 years, equity in higher ed and K-12 has been about disaggregating the data and then stepping back and admiring the problem," he said.

The structural changes colleges are making to replace remediation with corequisite courses -- in orientation, advising, curriculum and on and on -- "are putting new things into the lifeblood of our institutions for a generation, and there's a chance we can design them in equity-minded ways," he said.

Getting it right this time is key, he said. "What used to be nice is now necessary."

***

New York State's public colleges are big advocates for the use of open educational resources -- and not just because their state government has thrown its financial and strategic support behind their use (though that has certainly helped).

But faculty members and librarians at campuses in the City University of New York and State University of New York Systems aren't stopping at OER alone.

They want to create what two officials at CUNY's Borough of Manhattan Community College in their session Sunday called a "culture of open" -- an entire ecosystem that includes not just free and openly licensed educational materials (OER), but OER-enabled pedagogy, open educational practices, open pedagogy and open teaching.

That can mean things like moving from a closed platform (Blackboard) to "an open one like WordPress," said Gina Cherry, academic faculty development director of Manhattan's Center for Teaching, Learning and Scholarship.

It can involve events like the college's Open Teaching Week in April, when professors are encouraged to open their classrooms to peers, and online instructors, filling a conference room, give tours of their open online courses. (Last year's event also included a Wikipedia edit-athon.)

"This is not a product, it's a process," said Jean Amaral, open knowledge librarian at BMCC. She relayed surveys of instructors describing being "energized" and "liberated" from texts and traditions.

"So many of them talk about how transformative it has been," Amaral said, to "blow things up."

***

It's common for campus administrators and others to talk about the need to get faculty buy-in for meaningful changes in how a college or university delivers its instruction, whether it's online learning or using technology in the classroom, a new approach to assessing learning, or embracing active learning over lecturing.

Tony Holland, a former dean of instruction at Wallace Community College who now works for the Alabama Community College System, agrees wholeheartedly that instructional innovation is destined to fail without faculty support. But administrators who focus on buy-in are starting near the end rather than the beginning of a process that he relates to the five stages of grief.

Buy-in, after all, is another word for acceptance, and anyone familiar with Elisabeth Kübler-Ross's theory of how people process loss remembers that acceptance comes after people have worked through denial, anger, bargaining and depression.

In Holland's telling at his Innovations session, faculty members in many cases are dealing with being told that the way they've been trained and have operated heretofore in the classroom (read: lecturing, expecting every third student to fail, being in a physical classroom) is no longer the expectation.

As human beings, Holland says, professors -- like most of us -- "have a will not to change. We resist change."

What can overcome that natural resistance and move people from anger and denial to acceptance? The best idea is to provide a mission, a goal, so compelling that the "will to get to the objective can override the will to resist change," Holland said.

The one he uses for faculty members at Alabama's community colleges: the assertion that the "single greatest thing one can to do to increase opportunities in life is the pursuit of higher education," and the reality that Americans from low-income and underrepresented-minority backgrounds have far less access to those opportunities now. "We just talk about social justice in this country," he said.

Mission alone is not enough, of course, Holland said. Sometimes professors need to be jarred out of denial. He described a mix of strategies (involving training, support, encouragement and accountability) the Alabama colleges are using to inspire, motivate and persuade instructors to adopt instructional methods designed to close achievement gaps and increase retention and completion.

The system shares information from experts and peers around the country to help instructors realize how central their role is in students' success. It cites data from Valencia College, for instance, showing that students who withdraw from or fail even one of their first five course attempts graduate at half the rate of their peers. That can drive home to instructors how important it is that they not write off students unthinkingly.

Among the most significant approaches is using data to help faculty members understand that what they're accustomed to doing may not have been working. "I'm not going to use new techniques if I don't think there's a problem," Holland said. "If you're not putting data in front of the faculty, you're not doing anything."

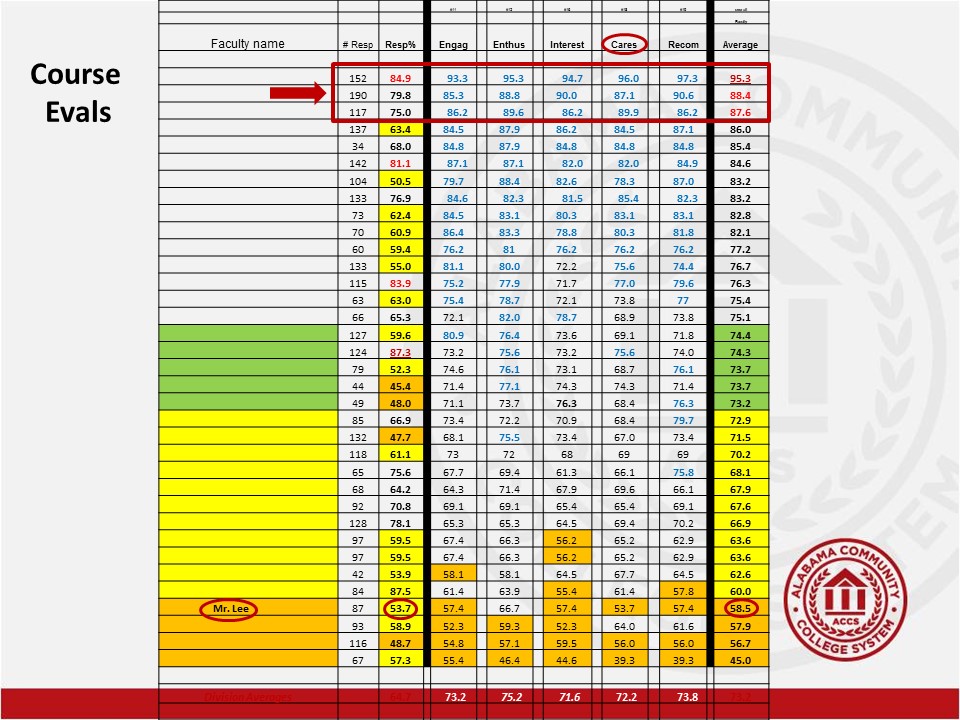

As seen in the slide below, for instance, Holland gives instructors data showing how students rate them (compared to their peers) on key traits associated with student success.

"Mind-set is so important, and data will help create the mind-set," he said. "You'll hear, 'I thought I was doing great.' You want to present data in a way that will inspire action."

Accountability matters, too, but the Alabama system strives, Holland said, to evaluate instructors or departments based not "on where they are, only on plans for improvement" and, ultimately, on whether they do improve.

Encouragement, though, matters as much as accountability, if not more. "You saw the data -- now what are you going to do about it?"