You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Eric Tornoe (right) and Xinyue Sui test out sentiment analysis software.

University of St. Thomas

How's everyone doing so far? Am I being clear? Anyone confused?

Professors might ask these questions midway through a lecture to get a sense of students’ moods. The scattered answers often aren’t very helpful, if they’re even accurate.

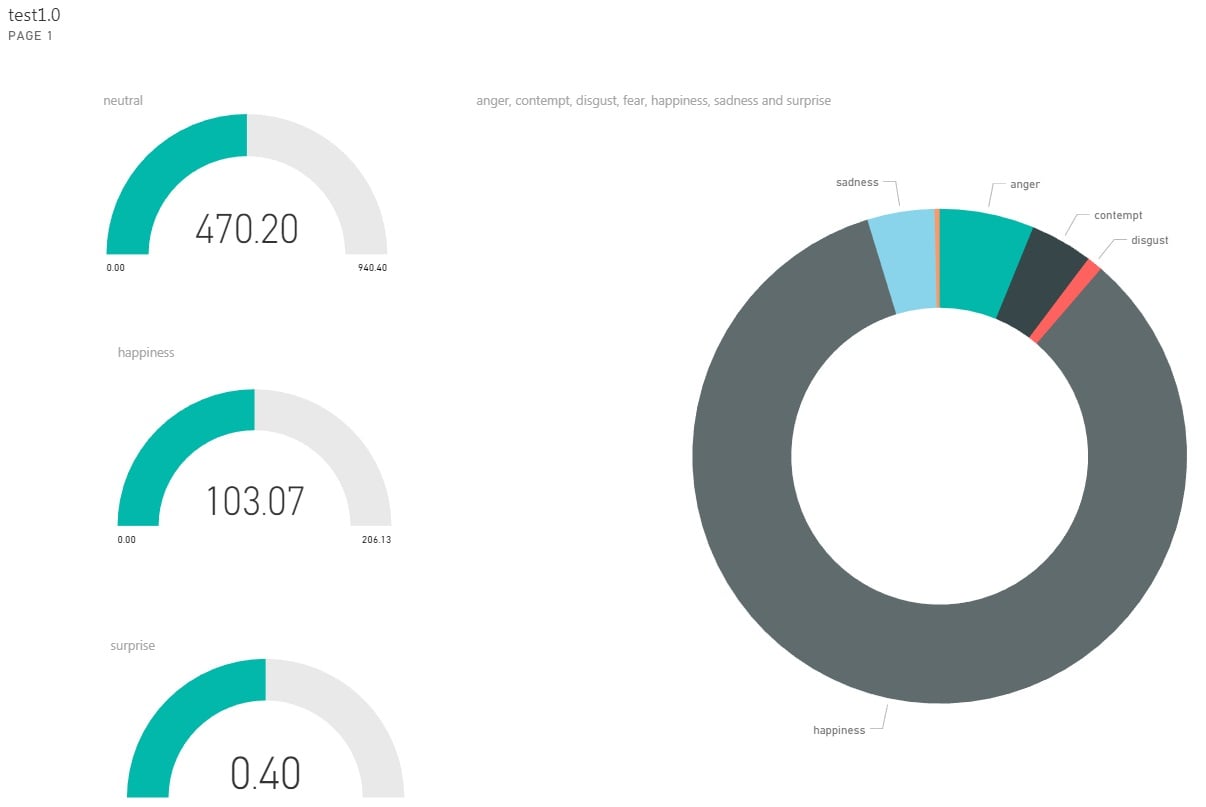

With sentiment analysis software, set for trial use later this semester in a classroom at the University of St. Thomas, in Minnesota, instructors don’t need to ask. Instead, they can glance at their computer screen at a particular point or stretch of time in the session and observe an aggregate of the emotions students are displaying on their faces: happiness, anger, contempt, disgust, fear, neutrality, sadness and surprise.

The project team hopes the software will help instructors tailor their teaching approaches to levels of student interest, and to address areas of concern, confusion and apathy from students. If most students drift into negative emotions midway through the session, an instructor could enliven that section with an active assignment. If half the students are happy and the other half aren’t, the latter group might be getting left behind.

Meanwhile, the "creepy" factor that pervades many new technology tools lingers over that potential. "Inside Digital Learning" talked to some analysts who worry that the superficial appeal of this affective computing technology might be obscuring larger concerns. Others, though, think this tool could be a worthwhile addition to a professor's own emotional judgment.

How It Began

The opportunity to develop this software came soon after the launch of St. Thomas’s E-Learning and Research Center (STELAR) last May. The team, led by Eric Tornoe, associate director of research computing in the information technology services department, hoped to start with a complex project that announced the center's capacity for impact. They jumped at the chance to meet at Microsoft’s technology center in Minneapolis.

During that visit, team members saw a demonstration of technology that could guess, with reasonable accuracy, ages and genders of people in the room. Tornoe started thinking about other applications of analysis technology, quickly landing on the potential information hidden within students' emotions. He envisioned professors using that information to ensure that a greater percentage of their lecture material stuck in students' minds and engaged them.

Microsoft lent Tornoe's team the facial recognition and emotion interfaces, free of charge, as well as the PowerBI software that provides a platform for those applications. Tornoe estimates the cost of processing analysis at $1 per minute.

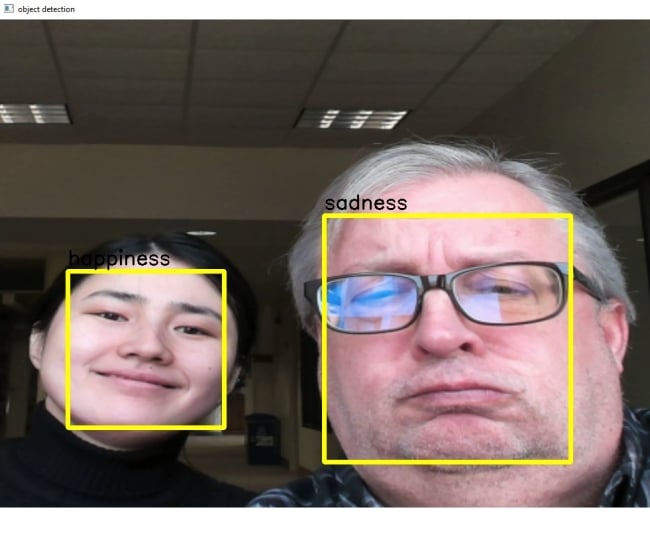

Here's how it works, per Tornoe: Python code captures video frames from a high-definition webcam and sends them to the Emotion interface, which determines the emotional state. Then that analysis comes to the Face interface, which returns the results, and draws a bounding box around the faces, along with a label for the given emotion. The Python code also sends the results to the PowerBI platform for visualization and retention.

Programming the software in Python proved complicated, Tornoe said, but now that it’s done, making quick changes is easy. The outfit can currently accommodate 42 student inputs at a time.

Tornoe, his assistant and a part-time student employee have served as the software's three main guinea pigs thus far. In the process of "pulling faces" to test different emotions, the team found that surprise and anger were the easiest to perform and detect, while contempt was the trickiest.

More Affect Tech

Researchers at Stanford University have been working for several years on a tool that detects confusion and distress in discussion forum posts. According to Andreas Paepcke, senior research scientist, the tool was conceived for use on MOOC platforms, but the team now thinks it could be applied to online and face-to-face courses as well.

The team also road tested the technology with unsuspecting audiences at staff meetings and presentations, according to Tornoe. (A spokesperson for the university said the staff meeting audiences were prepared to see a presentation about sentiment analysis, so they weren't caught entirely off guard.)

Tornoe said he’s “fairly confident” in the accuracy of the software’s determinations.

"Amusingly, once we got the result we were looking for, the next frame that came back always showed us all as 'happy,' which was genuine and spontaneous," he said.

This semester, pending approval from the university's Institutional Review Board, a finance professor will incorporate the software into his class as a "tuning trial," Tornoe said. The goals are to better understand how effectively students' emotions are being captured, determine optimal camera placement and point to other minor areas with room for improvement. This fall, pending board approval, the software will get a full trial.

The extent of the software’s implications for teaching and learning depends on the emotional analysis becoming more sophisticated over time.

“It doesn’t know what it doesn’t know,” Tornoe said.

How Private Is It?

Instructors won’t be able to see individual students’ emotions, either in real time or after the fact -- heading off any immediate complaints that the technology is invasive on a personal level.

Tornoe and his colleagues haven’t yet decided how much students will know about sentiment analysis before they're subjected to it; university administrators have final say over that decision, according to a spokesperson.

(Note: This article has been revised from an earlier version to clarify several facts, based on information from a university spokesperson.)

While people who know they’re being analyzed tend to spend some time early on “pulling faces” and trying to game the system, they eventually retreat to their normal stance, allowing for accurate analysis. Ethical questions -- at what point does collecting information on emotions become invasive? -- remain under consideration, though Tornoe is leaning toward providing disclosure to students up front.

Martin Kurzweil, director of the educational transformation program at Ithaka S&R, believes students need to know exactly how their information is being collected and how it will be used.

"In any context in which the data are being used to affect an individual student’s trajectory or what’s available to them or [their] grades, there needs to be some opportunity for appeal and human judgment and intervention," Kurzweil said.

Indeed, somewhat similar experiments don't have a sterling track record -- an outcry resulted in 2014 when Harvard University secretly photographed students with the goal of improving attendance collection.

What’s Next?

The team hopes to improve the software so that archived materials retain time stamps for more granular postclass analysis. Using the software in online courses is also a possibility with some adjustments, Tornoe said,

Tornoe also has a theory that more subtle emotions could be interpreted from the ones on the display. For instance, a low-grade “surprised” reaction might show comprehension.

The software currently requires a 1080p webcam, but Tornoe believes he can attach it to a more sophisticated camera -- perhaps even one that captures 360-degree images.

The project will have to overcome skepticism from observers like Kurzweil, who thinks that happy and frustrated faces could contain such a wide variety of meanings that drawing conclusions from them would be challenging.

George Siemens, executive director of LINK Research Lab at the University of Texas at Arlington, applauds the institution for its focus on students' emotions, but he says he doesn't see why technology is necessary to perform a task at which humans are intrinsically more capable.

"I think we’re solving a problem the wrong way," Siemens said. "Student engagement requires greater human involvement, not greater technology involvement."

Paepcke, of Stanford, whose team is working on its own tool to detect student emotions, sees it differently. Technology tools like this one aren't replacing humans' abilities but merely augmenting them. Instructors can incorporate the findings from sentiment analysis into their approaches without relying solely on them, he said.

"It’s not like the machine is completely clouding out the judgment of the instructor," Paepcke said. He sees other potential utilities as well: "You could also argue in very large classes, it’s harder for the instructor to constantly scan. Weaker students might be way in the back because they like to hide a little bit."

Paepcke wonders whether the technology might be even more effective if students can see real-time readouts of their emotions throughout the class. Then if they're confused, they have a better sense of how their peers are feeling -- and if they think the software isn't picking up their confusion, they can speak up by criticizing the technology instead of leading with their own lack of understanding.

For Tornoe, that idea is one of many that will require further study.

"I think the concept is fascinating enough that it could be exciting to students and generate interest for both the technology, the usage and the results," Tornoe said. "On the flip side, it might make them feel like they are in the Big Brother house!"