You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

International student enrollments decreased across the board in fall 2020 after the start of the pandemic, according to the new Open Doors survey.

Institute of International Education

The number of international students enrolled at U.S. colleges and universities has begun to rebound following a precipitous pandemic-related drop in international enrollments last fall, according to new data being released today.

The number of new international students increased by 68 percent this fall over last fall, and the number of total international students grew by 4 percent across more than 860 U.S. higher education institutions that responded to a “snapshot” survey on fall international enrollments conducted by the Institute of International Education (IIE) and nine other higher education associations.

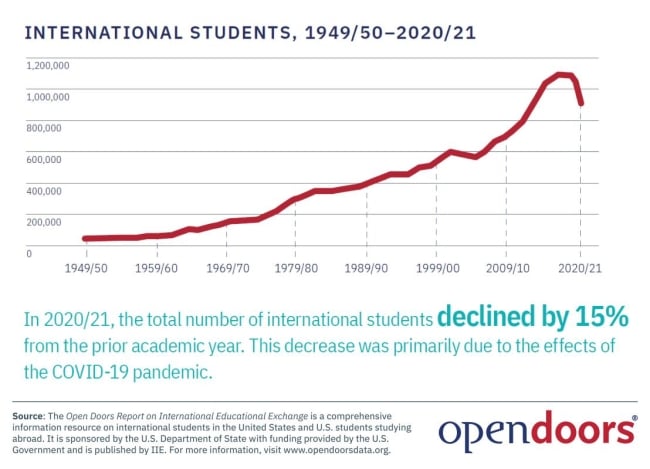

The increases this fall follow a 46 percent drop in new international students, and a 15 percent drop in total international students, in academic year 2020–21 compared to the year before. Those numbers come from the newly released Open Doors census of international enrollments, conducted annually by IIE with funding from the U.S. Department of State.

“The COVID-19 pandemic disrupted the international educational landscape on a global scale that had not happened before,” said Mirka Martel, head of research, evaluation and learning at IIE. “Many international students were not able to travel to the United States due to travel restrictions. U.S. universities showed incredible flexibility in offering many of these students the opportunity to begin or continue their studies online, whether in the United States or from abroad.”

Unlike in past years, when Open Doors only tracked the number of student visa holders enrolled in person at U.S. institutions, the newest Open Doors report uses an expanded definition of “international student” to include any international student studying in person or online at a U.S. university, including students who enrolled in online classes from overseas.

The majority of the international students in fall 2020 were enrolled exclusively in online classes: IIE found that only 41 percent of newly enrolled international students, and 47 percent of all international students, were able to attend a class in person in fall 2020.

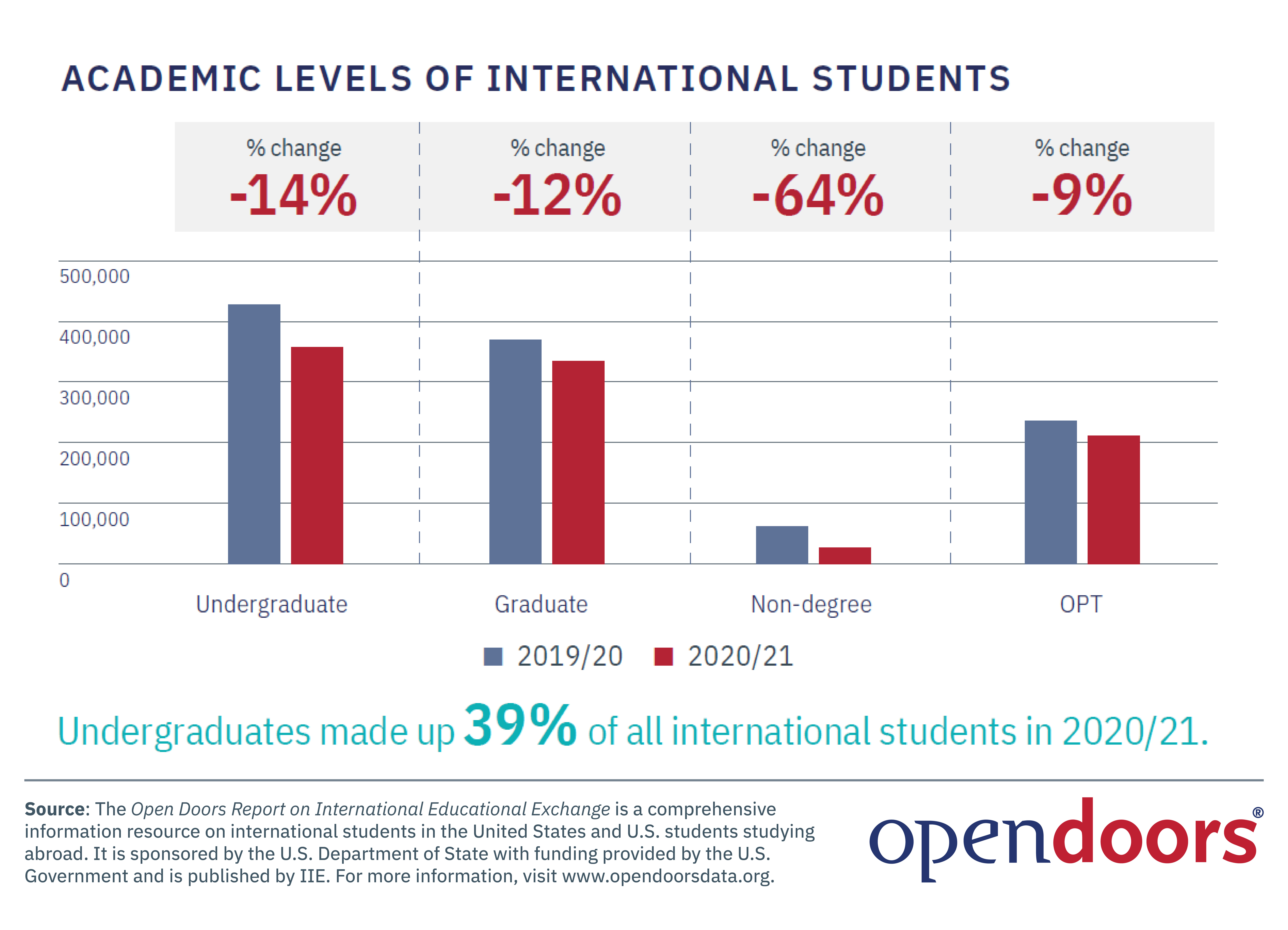

But even with the expanded flexibility universities offered for international students to take courses online, total international enrollments at U.S. colleges were down across the board in academic year 2020–21, from every major sending country, at every academic level (see infographic at left) and in every major field of study. The steepest drops were in intensive English programs, which reported a 61 percent drop in international enrollments.

But even with the expanded flexibility universities offered for international students to take courses online, total international enrollments at U.S. colleges were down across the board in academic year 2020–21, from every major sending country, at every academic level (see infographic at left) and in every major field of study. The steepest drops were in intensive English programs, which reported a 61 percent drop in international enrollments.

There were decreases in international enrollments across every sector of higher education, although the declines were steeper in some sectors than others. The total number of international students enrolled in 2020–21 fell by 13 percent at doctoral universities, 23 percent at master’s colleges and universities, 14 percent at baccalaureate colleges, and 24 percent at associate degree–granting colleges.

The snapshot survey data from this fall points to a resumption of in-person learning: 99 percent of the responding colleges said they’re offering their classes in person or in a hybrid format. And at least 65 percent of the international students enrolled at colleges that responded to the snapshot survey this fall are present here in the United States.

U.S. colleges said they are prioritizing outreach to prospective international students in India (56 percent) and China (51 percent)—together students in these two countries account for more than half of all international students in the U.S.—and to international students enrolled in U.S. high schools (44 percent). Colleges reported recruiting strategies including leveraging current international students (64 percent), online recruitment events (56 percent) and social media outreach (55 percent).

More than three-quarters (77 percent) said their recruitment budget is the same or higher than in previous years.

Not all institutions reported increases in international enrollments this year: while 70 percent reported increases in international enrollment, 10 percent said their numbers were flat, and 20 percent reported decreases.

The snapshot survey data for this fall do not include a breakdown of the change in international student numbers at the undergraduate versus the graduate level.

Allan E. Goodman, IIE’s chief executive officer, said the history of academic mobility during previous pandemics shows that “academic mobility occurs even during it, and when it’s controlled or when it’s over, there is a surge of the kind we very much hope to see, because people have deferred their dream to study abroad but haven’t abandoned it.”

The new data, Goodman said, “foreshadows that the same pattern will continue in the wake of this pandemic, that exchanges continued all during it … and it will increase and ramp up very rapidly in the years ahead.”

But William Brustein, the Eberly Family Distinguished Professor of History at West Virginia University and a former senior international officer at WVU and several other universities, said he is concerned about undergraduate international recruitment for many U.S. colleges in the years ahead. He cited a number of challenges, including the higher cost of higher education in the U.S. compared to many competitor countries, increasing competition for international students from other countries, geopolitical tensions between the U.S. and China, and concerns about the U.S.’s handling of the pandemic.

“The highly selective schools in the U.S. will continue to do well, but I think the community college sector and the state systems are not going to fare well when it comes to international student recruitment over the next few years,” Brustein said.

New international student enrollments had already been on the decline in the four years leading up to the start of the pandemic, decreasing by 3.3 percent in 2016–17, 6.6 percent in 2017–18, 0.9 percent in 2018–19 and 0.6 percent in 2019–20, according to Open Doors data. Many observers pointed to an unwelcoming political climate and Trump administration policies on immigration as being likely factors contributing to these decreases.

IIE and seven other major higher education associations—the American Association of Community Colleges, the American Association of State Colleges and Universities, the American Council on Education, the Association of American Universities, the Association of Public and Land-grant Universities, NAFSA: Association of International Educators, and the National Association of Independent Colleges and Universities—issued a statement today calling on the U.S. government to work with higher education institutions to develop a national strategy to return international student enrollment and exchanges to pre-COVID numbers.

The Departments of Education and State issued a joint statement in July articulating “a renewed U.S. commitment to international education,” which, advocates for international education hoped, could be a first step toward a federal strategy.

“It is essential that the federal government support higher education’s efforts to develop a national strategy to increase the number of international students enrolled at U.S. colleges and universities, ensuring that the nation returns to its pre-pandemic, high water mark level set in 2015 of more than 1 million international students,” the statement from the higher ed groups says.

U.S. Study Abroad

The Open Doors census also found a 53 percent drop in the number of American students studying abroad for credit in 2019–20, the year the pandemic began, compared to the year before. (While Open Doors reports on both international enrollments and the enrollments of U.S. students studying abroad, the study abroad data lag a year behind.)

U.S. colleges launched an unprecedented effort to evacuate their study abroad students from around the world in spring 2020, after the start of the pandemic.

“In total, over 867 institutions reported that approximately 55,000 U.S. students returned home safely amid the COVID-19 pandemic, due in large part to the tireless work of study abroad providers,” Martel said.

The near total suspension in U.S. study abroad can be starkly seen in the enrollments in summer 2020, when the number of students studying abroad fell by 99 percent compared to the year before. Summer is typically a busy time for study abroad, accounting for 39 percent of all study abroad enrollments in the 2018–19 academic year.

The numbers of U.S. students studying abroad declined in all major destination countries from 2018–19 to 2019–20, with the steepest decline—79 percent—being in China, where COVID-19 was first identified.

The proportion of racial and ethnic minority students among all students studying abroad decreased slightly from 2018–19 to 2019–20, from about 31 to 30 percent.

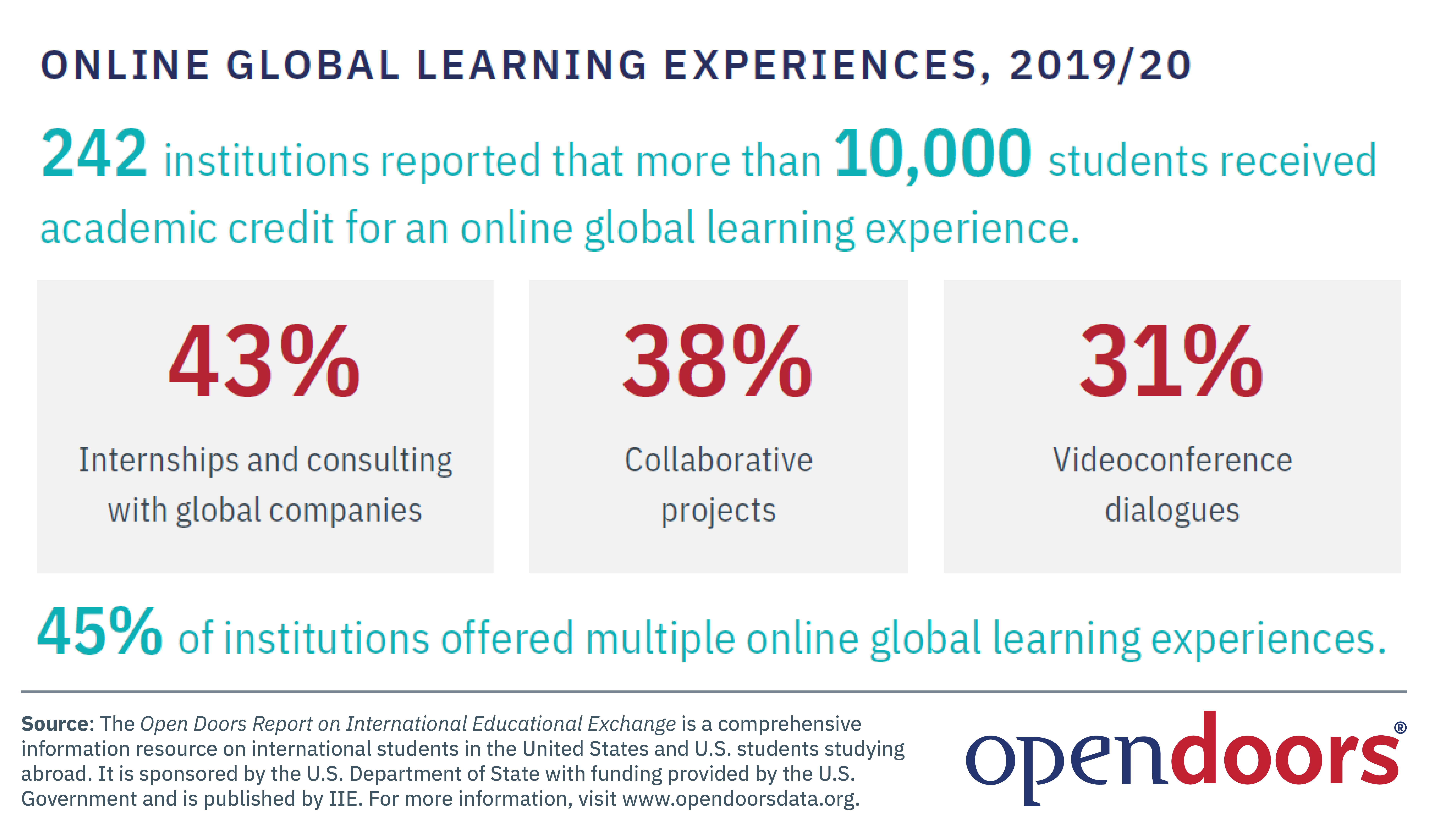

Many colleges and study abroad providers shifted their programs to virtual formats and expanded online offerings, including online global internships. A total of 242 institutions reported that more than 10,400 students received academic credit for an online global learning experience.

Many colleges and study abroad providers shifted their programs to virtual formats and expanded online offerings, including online global internships. A total of 242 institutions reported that more than 10,400 students received academic credit for an online global learning experience.

Melissa Torres, president and CEO of the Forum on Education Abroad, a professional association for the field, said many colleges she’s spoken with have resumed sending students abroad to select destinations this fall—“and many more are seeing the pool of destinations opening, both from the standpoint of countries allowing visitors in and also that schools are lifting some of their travel restrictions.”

At the same time, she said colleges have become more risk averse. “I think the ed abroad offices are having to really demonstrate even more than they usually do why particular destinations are safer than others.”

“The Open Doors report is sobering but not surprising,” Torres said. “I think in education abroad, the sense that I’m getting from colleagues is that there’s finally some light at the end of the tunnel, and it’s not just the next train. It’s been a very, very long 19 months. There’s a lot to do to get back to where we were on the capacity side.”