You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

iStock

The scandal in college admissions captured public attention last week with many expressing surprise that the system was not a pure meritocracy before the bribery scheme was hatched, and is unlikely to become one even if all 50 of those indicted are convicted.

Jon Boeckenstedt, associate vice president for enrollment management and marketing at DePaul University, offered his critique of this reaction among journalists:

For starters, consider the wealth of those enrolled at the colleges in the scandal. At the University of Southern California, at the center of the indictments, 14 percent of students are from the top 1 percent of family income in the United States, while only 4.9 percent are from the bottom 20 percent, according to data from Opportunity Insights, the study launched by Raj Chetty of Harvard University with The New York Times.

At USC and at Georgetown, Stanford and Yale Universities -- others among the private universities allegedly the target of admissions bribes by wealthy parents -- those in the top 1 percent exceeded those in the bottom 20 percent of family income by three to four times. At all four of those institutions, more than half of students are from the top 10 percent of family income nationally.

At the University of Texas at Austin, a public institution caught up in the scandal, only 38 percent of students come from the top 10 percent of family income, and those in the bottom 20 percent slightly outnumber those in the top 1 percent (6 percent to 5.4 percent).

At all of the universities named above, those low-income students who are admitted benefit from generous aid programs and are much less likely to need to borrow or to borrow large sums than they would be at other institutions, but there just aren't that many of them admitted, compared to those from the higher levels of family income. It is also the case, of course, that many of those admitted from wealthy families at these elite colleges are in fact smart and accomplished -- and didn't bribe anyone, fake their test scores or invent false athletic identities.

All of the colleges linked to the scandal -- and many other competitive colleges and universities thus far untouched by it -- profess that they want to enroll more students from low-income families. What are the explanations for why that doesn't happen? Some of the factors involve societal inequalities that extend beyond higher education. Others relate to colleges' policies and practices. Here are some factors experts cite -- some of the ideas have been discussed for years. Other findings are more recent.

All of the colleges linked to the scandal -- and many other competitive colleges and universities thus far untouched by it -- profess that they want to enroll more students from low-income families. What are the explanations for why that doesn't happen? Some of the factors involve societal inequalities that extend beyond higher education. Others relate to colleges' policies and practices. Here are some factors experts cite -- some of the ideas have been discussed for years. Other findings are more recent.

Counselors: At the center of the current scandal is what was once a legitimate private counseling company. The reality is that most low-income students in the United States rely on high school counselors to guide them through the college admissions process. Many high schools that serve these students have deeply committed counselors, but they serve so many students that they can't possibly provide much individualized attention.

The American School Counselor Association recommends a student-counselor ration of no more than 250 to one, a ratio met by only three states (New Hampshire, Vermont and Wyoming). A study the association did with the National Association for College Admission Counseling found that the national average is 482 to one. In Arizona, the ratio is 924 to one. In California, the state has been making progress in bringing down the ratio, which was over 1,000 to one as recently as 2010. But that progress has brought it down to 760 to one.

Compare that to the individualized attention available to those who hire private counselors to guide families through the process. While many of those counselors talk of taking on pro bono clients, the general practice is to charge. According to the Independent Educational Consultants Association, comprehensive packages for a student range from $850 to $10,000, while the average hourly fee is $200. Such fee levels mean that many middle-class families are able to find private counselors, but the wealthy have access to services that are priced beyond the reach of most Americans. In 2005, Inside Higher Ed wrote about a three-and-one-half-day workshop for which the fee was $9,999. Last year, Inside Higher Ed wrote about a service that charged $1.5 million to help an applicant seek admission to 22 colleges.

The inequities in counselor access also extend to issues such as class size in high schools and the availability of advanced course offerings.

Essay "help": Beyond private counselors, a growing number of wealthy applicants are hiring people to help them write their college essays. Those in the field say that they coach applicants and don't write essays for them, although many say that they know of less reputable people who do write essays. Counselors also report that they must coach parents not to write the essays, and that they must stress that an essay in too adult a voice will be presumed to be written by someone other than the applicant.

Such services don't come cheap. One writing coach charges $2,500 for complete service through the process. Another charges $1,500 for the basic Common Application essay and then $700 for help on each supplemental essay. Most of these writing coaches report that their clients have already hired private counselors.

Testing: Some wealthy students do poorly on the SAT and ACT, and some low-income students excel. And a growing number of colleges don't require SAT or ACT scores. But many of the most elite colleges (all of the Ivies and Stanford, for example) still require test scores. So does USC.

While the College Board varies in the information it releases about students' family income and test scores, the data are consistent: wealthier students, on average, earn higher scores. For the most recent year, the average combined score on reading and mathematics was 990 for those who received fee waivers that are available to low-income students. The average was 1088 for those who didn't receive waivers. The waivers cover two SATs, but those who pay for the SAT can take the test as many times as they would like.

While the College Board varies in the information it releases about students' family income and test scores, the data are consistent: wealthier students, on average, earn higher scores. For the most recent year, the average combined score on reading and mathematics was 990 for those who received fee waivers that are available to low-income students. The average was 1088 for those who didn't receive waivers. The waivers cover two SATs, but those who pay for the SAT can take the test as many times as they would like.

The College Board promotes free help on the SAT from the Khan Academy, but wealthy families can arrange all kind of coaching and classes for their children.

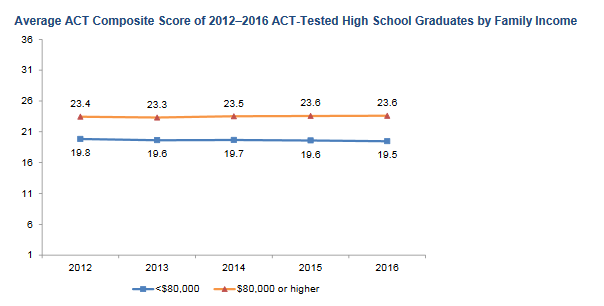

The ACT has found that those from families with incomes of at least $80,000 outperform others. (The trends by income noted for standardized tests are also true for race and ethnicity, with white and Asian American students, on average, earning better scores than do black and Latinx students.)

Where Colleges Recruit

Numerous studies have found that colleges are more likely to recruit at high schools with wealthy students than students whose families are middle class or poor. In 2012, Caroline M. Hoxby and Christopher Avery kicked off discussion of "undermatching" with their study that found that more than half of high-academic-achievement, low-income students never apply to a single competitive college. They and others suggested that colleges are looking for these students at a relatively small number of magnet schools, and not recruiting at the more typical high schools.

A 2013 project by the Los Angeles Times explored the issue by looking at high schools in the Los Angeles area and counting the number of college visits. At the Webb Schools, an elite private school, a greater number of colleges (113) visited in the year studied than the total number of 12th graders (106).

By comparison, at Jefferson High School, in a low-income part of Los Angeles, only eight recruiters came for a graduating class of 280. Those recruiting at such high schools were generally local, noncompetitive public institutions.

With the economic downturn that started in 2008, many states made deep cuts in appropriations for higher education, and many public colleges and universities stepped up recruitment of out-of-state students, who are charged higher tuition rates. A study presented at the annual meeting of the American Educational Research Association in 2013 found that state universities that increased the proportion of out-of-state students saw declines in the enrollment of minority and low-income students.

Ozan Jaquette, an assistant professor of education at the University of California, Los Angeles, was one of those involved with the study on demographic shifts following an increase in out-of-state enrollment. He is also one of the lead researchers on the Off-Campus Recruiting Research Project, which looks at where colleges and universities recruit. Among the findings:

- Colleges and universities appear to prioritize wealthy high schools, with many visiting high schools where average family income in the neighborhood served is in excess of $100,000, and skipping nearby high schools where average family income is around $60,000 to $70,000.

- Generally visits to out-of-state high schools by public universities are to those that serve neighborhoods with higher average family income than those of the high schools visited in the state.

- The high schools visited almost always have a majority of white students, sometimes with very high percentages of white students. Nearby high schools that are skipped tend to have much smaller shares of white students, and typically are high schools where white students are in the minority.

- Many colleges appear to visit a disproportionate number of private high schools.

"Demonstrated interest": This is one of the admissions criteria used by many competitive colleges. The term refers to ways that an applicant shows he or she is serious about enrolling at a given college. An applicant who calls with questions about a particular program is more valued than one who doesn't communicate beyond applying. An applicant who visits shows more demonstrated interest than one who doesn't, and so forth. Many colleges factor in demonstrated interest to admissions and aid decisions, wanting to admit applicants who will enroll. The idea is to have better planning and to improve the yield, the percentage of admitted applicants who enroll. And the theory has been found to be accurate -- those with more demonstrated interest are more likely to enroll.

But a study by Lehigh University economists published last year in Contemporary Economics Policy found that colleges most favor demonstrated interest of the kind that costs money. A student who visits campus, and does so long enough to participate in activities, will gain much more of an edge than an equally qualified student who talks with a college representative at a college fair at her school. Families that are wealthier are more likely to be able to take college trips and show that interest.

Early decision: In theory early decision -- in which students apply early and find out if they are admitted early, well before the normal deadline -- does not cost any more than regular decision. In binding early decision, the applicant must pledge to enroll if admitted. But many studies have found that those most likely to apply early (when admit rates tend to be higher) are more wealthy than other students. The earlier deadlines favor those who have received good counseling and had time to plan their college search process early. Likewise, many applicants from low-income families hesitate to participate in binding programs because they feel the need to compare aid packages from multiple institutions.

Early decision: In theory early decision -- in which students apply early and find out if they are admitted early, well before the normal deadline -- does not cost any more than regular decision. In binding early decision, the applicant must pledge to enroll if admitted. But many studies have found that those most likely to apply early (when admit rates tend to be higher) are more wealthy than other students. The earlier deadlines favor those who have received good counseling and had time to plan their college search process early. Likewise, many applicants from low-income families hesitate to participate in binding programs because they feel the need to compare aid packages from multiple institutions.

An analysis by the Jack Kent Cooke Foundation pointed to evidence about who applies early. "Twenty-nine percent of high-achieving students from families making more than $250,000 a year applied early decision, compared with only 16 percent of high-achieving students from families with incomes less than $50,000. In short, low-income students are half as likely to apply early, even though doing so would dramatically increase their likelihood of admission."

Despite that and similar studies, many elite colleges are admitting larger and larger shares of their classes early. And more students are applying early. Brown University saw early applications go up 21 percent this admissions cycle. Duke University saw an increase of 19 percent.

Legacy preferences: In the United States, graduating from a college is associated with higher levels of educational attainment and standardized test scores for graduates' children. Legacy preferences -- in which colleges favor the children of alumni -- add to those advantages.

In last year's Inside Higher Ed survey of admissions leaders, 42 percent of admissions directors at private colleges and universities said that legacy status is a factor in admissions decisions at their institutions. The figure at public institutions is only 6 percent. (In some cases, the preference at public institutions is to grant alumni children in-state status even if they are from out of state, and that can make a significant difference in a candidate's odds of admission.)

An analysis of the issue by Michael Dannenberg of Education Reform Now noted the prevalence of legacy preferences at a time of legal challenges to policies that may help boost the enrollment of black and Latinx students.

"More white students are admitted to top 10 universities under an alumni preference bonus than the total number of black and Latinx students admitted under affirmative action policies," he wrote. "By definition, zero students benefiting from an alumni preference are first-generation college applicants. Virtually no legacy student attending an elite institution is low income." He cited research finding that, at some colleges, legacy applicants are significantly more likely than nonlegacies to be admitted.

Some of the documents released in the current lawsuit against Harvard University over its admissions policies have indicated that the use of legacy preferences (as well as preferences for athletes) is a major factor in explaining why the high academic ratings of many Asian American applicants do not translate into admissions offers. In 1990, the U.S. Education Department investigated Harvard's legacy preferences and found them to be legal. In that investigation, documents from which Inside Higher Ed obtained under an open-records request, some of the comments on legacy applicants' files said things like:

- "Well not much to say here. [Applicant] is a good student, w/average ECs [extracurriculars], standard athletics, middle-of-the-road scores, good support and 2 legacy legs to stand on … Let's see what alum thinks and how far the H/R [Harvard/Radcliffe] tip will go."

- "Not a great profile but just strong enough #s and grades to get the tip from lineage."

- "Without lineage, there would be little case. With it, we'll keep looking."

The Education Department in 1990 found that these preferences were legal, noting that Harvard cited the need to motivate alumni, and that Harvard had started the policy in the early 1900s, so it could not be said it was used to exclude Asian Americans.

New America recently asked Congress to bar legacy preferences. "Historically, the college admissions landscape at highly selective institutions has been sustained by policies that favor the white and wealthy, propping up a status quo that blocks access to low-income students of color. Chief among those policies is the practice of giving preference to legacy students," the New America proposal says.

"While race-conscious admissions policies are the constant target of undeserved scrutiny, legacy preference has gone mostly unchallenged legally, to great effect … Congress should withhold Title IV aid [federal student aid] to those highly resourced and highly selective institutions that engage in legacy admissions and other preferential admissions treatments that overwhelmingly favor wealthy and white families, including early-decision programs."

The Council for Advancement and Support of Education, an organization that includes college fund-raisers, is opposing the New America proposal.

Minimal transfers: In states such as Florida and California, transfer admissions -- primarily from community colleges -- are a major source of socioeconomic diversity at public universities. At places like the University of California, Berkeley, which is barred by the state from considering race in admissions, transfer admissions also add significantly to black and Latinx enrollment. Berkeley this year enrolled 221 new black transfer students and many more Latinx transfer students (and students of other backgrounds). Elite private colleges, in contrast, tend to enroll relatively few transfer students. A report released in January by the Jack Kent Cooke Foundation found that relatively few community college transfers are admitted to elite private colleges, even though those who enroll do succeed and are more likely than those admitted as freshmen to be from underrepresented minority groups, from low-income backgrounds or to be veterans of the U.S. military.

Consider Princeton University, which in 1990 abandoned transfer admissions. The university's board agreed in 2016 to come up with a plan to again admit transfer students and in May announced that it had admitted 13 transfer applicants. They are among the 1,429 who applied. Of those admitted, eight identify as people of color, including biracial and multiracial students. Eight have served in or are still serving in the military. Eight studied at community colleges. None of those admitted are recruited athletes. Princeton's total number of transfer admits is similar to those at Harvard and Stanford.

Consider other numbers of those admitted to Princeton from individual nationally known prep schools. The Lawrenceville School reported that, in the last three admissions cycles, 34 of its students were admitted to Princeton. From Choate Rosemary Hall, the figure was 16 over the last five years. From Phillips Academy, the figure was five in the last year, and at least 20 in the last three years.

Rankings: For years, many have said that the rankings by U.S. News & World Report favor institutions that admit wealthy students. This year, the rankings methodology changed, and the magazine hailed the changes as a sign that it was promoting social mobility in higher education. Indeed some colleges in the middle of the rankings, with good records on enrolling low-income students, saw their rankings go up.

But the new methodology did not disrupt the top of the rankings. Who was No. 1 in the new social mobility-influenced U.S. News rankings? Princeton University. Who is No. 2? Harvard University. That would be the same top two as last year, before the changes. And you'll find Ivies and similarly prestigious institutions continue to do quite well -- despite having a fraction of the disadvantaged students enrolled elsewhere. Generally the rankings gave those and other institutions credit for graduating high numbers of the low-income students admitted but did not punish the institutions for not admitting more such applicants.

But the new methodology did not disrupt the top of the rankings. Who was No. 1 in the new social mobility-influenced U.S. News rankings? Princeton University. Who is No. 2? Harvard University. That would be the same top two as last year, before the changes. And you'll find Ivies and similarly prestigious institutions continue to do quite well -- despite having a fraction of the disadvantaged students enrolled elsewhere. Generally the rankings gave those and other institutions credit for graduating high numbers of the low-income students admitted but did not punish the institutions for not admitting more such applicants.

Six Democratic senators complained to U.S. News that, even with the changes, its rankings were promoting the wrong values: "As the primary mass media arbiter of college prestige relied upon by many students, families and colleges, U.S. News has an obligation to assess American higher education fairly. U.S. News should acknowledge and correct for the role its rankings have played in fueling the collegiate arms race and preserving regressive admission policies like legacy enrollment and early decision. This approach prioritizes prestige and exacerbates America's deeply ingrained and racialized wealth disparities."

U.S. News indicated that it planned no changes as a result of the letter but would continue to study the issue. "Many schools that serve low-income populations do not fare so well. Interestingly, so-called elite schools often perform quite well on this measure, as there is a clear correlation between the wealth of a school and its ability to serve all of its students. We will continue to study this data, take feedback, and make refinements as necessary," said a letter to the senators from Brian Kelly, editor and chief content officer of U.S. News.