You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Getty Images

Professors' views about the role of technology in learning are easy to caricature. Some faculty members cling to their yellowed lecture notes and reject new technology-enabled approaches because they believe what they're doing works, to be sure, but the common assertion that professors stand in lock-step opposition to the use of technology doesn't hold up to scrutiny amid the many examples of experimentation and creativity that appear regularly in these pages.

That's not to say that the college faculty is engaged in wholesale embrace of digital learning, either. A new survey of faculty members and administrators by Tyton Partners asserts that the use of digital instructional technologies, which it endorses, is facing "headwinds" in adoption by colleges and universities. The study identifies faculty take-up of digital courseware and other tools as among the leading impediments to their spread -- but cites faculty members' lack of time and the training they receive from their institutions as far bigger cause than their outright opposition.

"The majority of surveyed administrators agreed that faculty are crucial to the success of digital learning initiatives -- serving as both a bolster and a barrier to implementation success," the report states. "Yet reports from both administrators and faculty suggest that the resources to support faculty to implement digital learning are lacking."

Tyton is an investment banking and strategy consulting firm. It may be best known to people in the digital learning space for its reports on topics such as adaptive learning and as the creator of the Courseware in Context Framework, which aims to help colleges understand and assess various digital courseware tools. This survey -- conducted with the Babson Survey Research Group with support from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation -- represents Tyton's second scan of faculty and administrative opinion on digital courseware and learning broadly, following an analysis in 2015.

Tyton acknowledges upfront its bias in favor of using technology to deliver instruction: "[W]e believe that quality digital learning programs can deliver flexible and personalized education that meets the needs of today's learners and institutions." To make that case, the report presents federal data showing that colleges and universities with more online enrollments produce more credentials and spend less per credential they award.

Gates Bryant, a partner at Tyton and a co-author of the report, said those data provide "irrefutable evidence that online learning plays a positive role in better outcomes at lower overall costs." That, he said, is because digital learning "helps institutions provide flexible access to courses that are otherwise difficult to get into, and frees up capacity where enrollment may be constrained by physical plant capacity or number of instructors."

Limited Evidence and Much Skepticism

While the Tyton report is unabashed in asserting the potential value of digital learning, it acknowledges that "evidence of the impacts of digital learning ... is limited, and many decision-makers remain skeptical" about it. And legitimate questions about quality remain, Bryant said. "So our perspective is this: It's not a question of whether we should be doing digital learning or offering online courses. It's, how do we scale them, and how do we make sure it's instruction that spreads and improves the quality of learning."

The survey of roughly 2,300 instructors and 1,200 administrators aims to find out what stands in the way of broader embrace and implementation of digital learning initiatives by colleges and universities. The survey finds four major barriers to adoption: a lack of strategic planning by institutions, a dearth of support for faculty members, decentralized decision making, and low satisfaction with courseware products.

It's not that colleges aren't trying to plan strategically; a majority of surveyed administrators from all types of institutions said that their strategic plans account for digital learning, and a quarter said it was a primary focus.

But achieving those goals is another matter: asked whether they had made progress in using digital learning to address key priorities such as identifying alternative revenue streams, increasing retention, and becoming more cost effective, majorities said they had either made little progress or that it was too early to tell.

The Faculty's Key Role

The report's heading on the role of instructors in implementing digital learning couldn't be much more blunt: "Faculty are a linchpin in digital learning success, yet they are woefully undersupported."

Asked to identify the most important factors to successful implementation of digital learning, nearly 7 in 10 of the administrators surveyed answered "support for faculty professional development," and the third most common answer was "incentives for faculty practice change/course redevelopment effort."

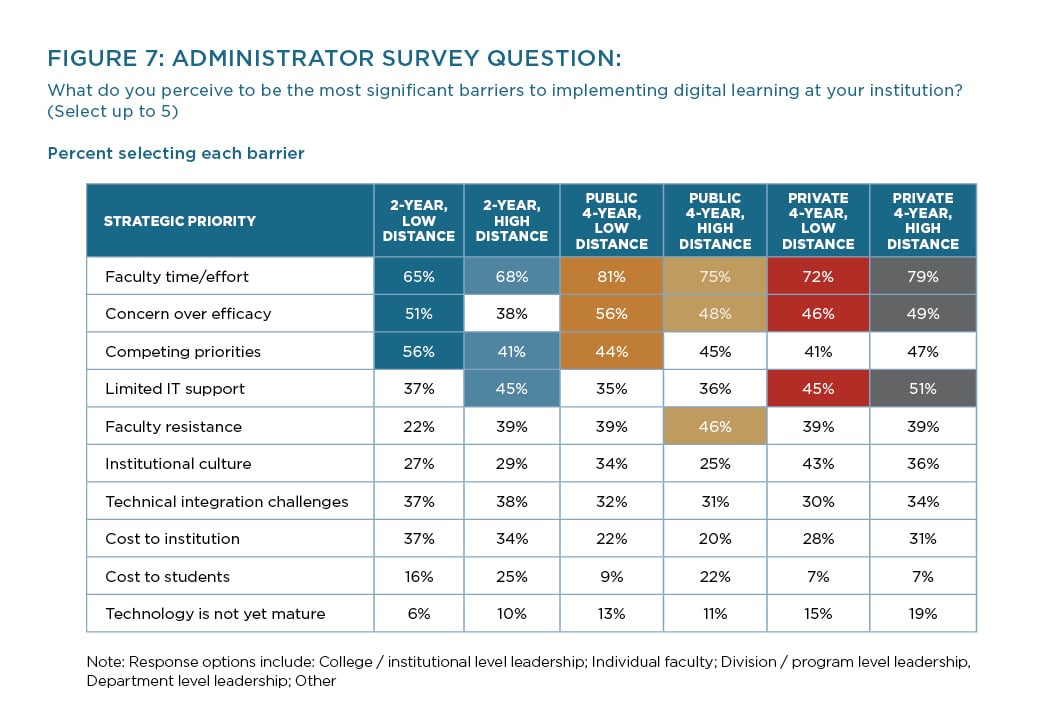

And asked to identify the "most significant barriers to implementing digital learning" at their institutions, between two-thirds and four-fifths of the administrators (depending on the type of institution) cited "faculty time/effort," more than any other choice.

Next in order, as seen in the table below, were their "concern over efficacy" (roughly half), competing priorities, and limited IT support -- and only then did "faculty resistance" appear, identified by about two in five respondents. About a third of administrative respondents cited "institutional culture" as a barrier.

But despite recognizing the importance of giving faculty members training to use technology effectively, administrators acknowledged that their institutions weren't doing it very well. Only a quarter of them said they were giving professors professional development for digital learning implementation "effectively and at scale," while a third described their support as "incomplete, inconsistent, informal and/or optional."

This response was typical: "Without real support for learning and measuring the usefulness of new pedagogies, faculty cannot be expected to make headway in successfully integrating technology in their courses," said one administrator at a four-year public that has a significant proportion of online students. "Some individual faculty members really like technology and end up as standouts in its use, but the university has a tendency to promote the achievements of this small group and to ignore the fact that there is no systematic support for transforming to effective digital pedagogies."

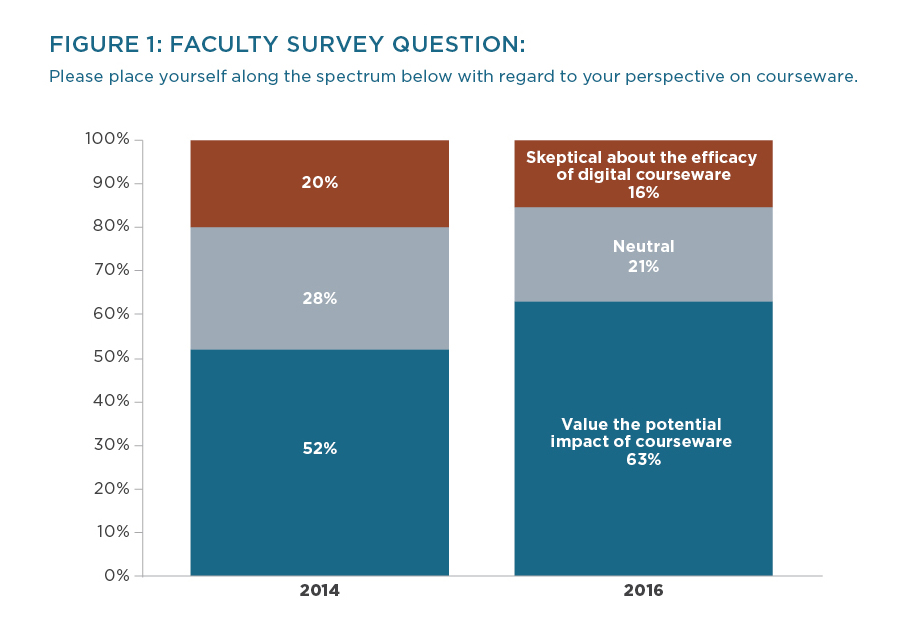

The survey does reveal some faculty opposition to the use of digital learning: about 16 percent of professors described themselves as "skeptical about the efficacy of digital courseware," and another 21 percent said they were neutral. (Nearly two-thirds say they "value the potential of digital courseware," up from 52 percent two years earlier, as seen in the graphic below.) And 40 percent characterized themselves as adopters only of "well-proven technology" (as opposed to new tools and approaches).

But more of them than not (39 percent to 21 percent) said they had a "tendency toward exploratory teaching methods" rather than toward "proven instructional methods" and a preference for

"facilitated exploration of content" rather than lecturing.

More Training Required

Those proclivities toward trying new approaches are not going to realized, Tyton argues, if college and university leaders do not give professors more training, time and incentives to experiment and better tools for helping faculty members choose and use new technologies.

"If meeting institutional goals hinges on the successful and scaled implementation of digital learning," Tyton's report states, "faculty must buy in to the strategy and be equipped to execute the implementation with a clear line of sight into goals, sufficient training, and incentives (or a lack of disincentives) for change."