You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

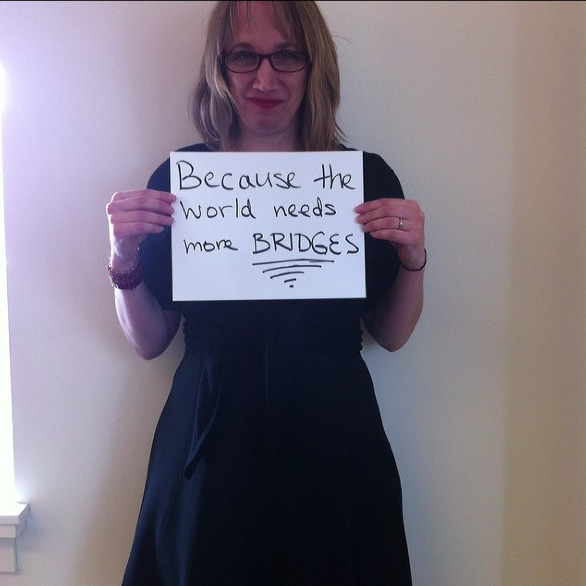

The second post in our series, Scholars Strike Back, features Deborah Siegel. Siegel is a writer, TEDx speaker, and consultant who received her PhD in English and American Literature. She is currently a Visiting Scholar in Gender and Sexuality Studies at Northwestern University. If you are interested in participating in this series, please contact associate editor, Gwendolyn Beetham.

In the wake of the recent public debate about scholars’ debating in public, academics have rightly catalogued the structural barriers to going mainstream and following Kristof’s call (“Professors, We Need You!”). As Gwendolyn Beetham sagely kicked off for us here, and others have elsewhere, the race, class, and gender dynamics of public scholarship continue to color what narratives are replayed and whose stories are told. There’s been strong documentation of all the ways a diverse range of scholars are engaging publicly, and the need to make it count. What’s still needed in this discussion is more acknowledgment of the unabashed upsides of going public, for all parties involved—colleges and universities too.

As the creator of a crossover blog (Girl w/Pen), co-founder of the web journal The Scholar and Feminist Online, and a facilitator with The OpEd Project, I’ve seen engaged academics, many (if not most) of them women, some on the fence of leaving academe, come to feel that by allowing themselves a public voice in addition to their scholarly one, they can keep a toehold in both worlds. For those academics yearning for that sense of expanded relevance and wider engagement, outlets like these and others can function as a release valve. To know the choice doesn't have to be either/or may keep some of our most engaged thinkers from leaving the fold, while simultaneously keeping our public debate infused with some of the best thinking there is.

Needless to say, the professional gains, outside of academia, are immeasurable: book contracts, invitations to testify before Congress, TEDx invites, national tv and radio appearances, funding, readership. Nearly all of these things can and have happened within any one OpEd Project Public Voices faculty program, including the fellowship I direct at DePaul University.

So, yes, scholars who write publicly report a heightened sense of personal relevance, and when media is informed by actual experts, the public is better-informed. What’s less widely acknowledged, because it is far less common, is that in more than a few pockets, institutions of higher education may be starting to see the upsides for themselves, too.

What are those institutional upsides? I canvassed a number of the scholars I’ve worked with over the years to find out what, if any, have been the gains, from their institution’s perspective. Here’s what some of them said.

First, publicly engaged scholars engender engaged students, and engaged students are good for all. Says Shira Tarrant, a professor of Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies at Cal State-Long Beach, who writes about sexual politics, masculinity, and pop culture issues for several blogs, magazines, and popular outlets including Girl w/Pen, Huffington Post, AlterNet, and Bitch that get picked up and reposted by other venues, “I use the mainstream material [I produce] in my course curriculum and assignments. It's accessible and provides a way in to discuss broader issues or to synthesize theory with current politics.” In addition to keeping topics relevant for students, faculty’s public work breaks down silos. Notes Winifred Curran, a professor of Geography at DePaul University, “My op-ed about the sexism of snow removal is perhaps the only thing I've written that my students have actually read, and not because I assigned it to them. Through the twitterverse, a number of previous students retweeted and posted on Facebook so that some of my current students saw the piece and asked me about it after class. One student is using it as a source for a paper on the city's response to extreme weather in the age of climate change.” Asked what impact she thinks this might have on the higher ups, Curran says, “They don’t know about it yet, but I shall make it my business to tell them. I think they'll be pretty jazzed.”

Second, necessity. With academic presses—and the traditional publishing industry in general—struggling, faculty have to write for wider audiences or else they’ll have few places left in which to publish. Karlyn Crowley, a professor of English, Director of Women’s and Gender Studies at St. Norbert College, and Girl w/Pen’s newest blogger, is optimistic. “Faculty have to appeal to wider audiences and tenure/promotion committees have to see that as legitimate,” she says. Virginia Rutter, a professor of Sociology at Framingham State University who sits on the board of the Council on Contemporary Families (a group of scholars who exist in order to make social science research on family diversity and family change accessible), is deeply engaged in that appeal. She notes that numerous columns from Girl w/Pen, Sociological Images and Cyborgology—all blogs housed at The Society Pages—will be included in a Norton Anthology, a high-profile edited volume that expressly incorporates scholarly (but accessibly written) chapters along with news and social media coverage of key topics on family diversity, called Families as They Really Are. “Now these will be lines in people’s vitas,” Rutter says, adding that, at Framingham, her Academic Vice President encourages engagement in public platforms.

I’ve seen other publicly engaged scholars receive similar acknowledgement of their work from the higher ups. Says Tarrant, “I’ve received generous institutional support in the form of course release, formal acknowledgement, and a nice relationship with the campus media office, which sends reporters to me regularly.” After DePaul professor of English Michelle Navarre Cleary published a piece in The Atlantic that received over 18,000 Facebook shares, the university gave her media training to help her prepare for subsequent radio interviews. As a result, in part, of writing a piece here at Inside Higher Ed, Cleary’s dean identified her as one of the university’s leading experts on competency based education and the Office of Public Relations and Communications directed media to her through an alert.

Perhaps certain kinds of institutions are more open to “counting” this work than others, for now. Says Crowley, “My hunch is that the small, liberal-arts college may lead the way in being more willing to accept ‘cross-over’ publications as legitimate intellectual work.” When asked what St. Norbert College is doing to this effect, Crowley said, “My school is thrilled that I have a regular writing outlet on the cusp of academia; they're even starting an op-ed group to get more folks to write publicly—a handful of faculty to start plus the president since he's a terrific writer and accomplished author/journalist, himself.”

Small liberal arts colleges may, in some cases, lead the way, but over a dozen universities, including a number of R1s, have now engaged or are engaging The OpEd Project, offering their faculty professional development along these very lines. Says Carolyn Bronstein, the DePaul professor of Communication responsible for bringing the Public Voices fellowship to her colleagues, “DePaul ran the program two years in a row and paid for it, investing in training faculty and staff to have a public voice. And the public relations office compiles a weekly email of ‘DePaul in the News’ and highlights all the faculty and staff who are in the media—another metric that shows that this matters at the university.” At Northwestern University, which has run the year-long fellowship program, now, two years in a row, the Provost’s office highlights fellows’ opeds regularly on its website, and the President features the program in the strategic plan. Stories featuring the public work of their institution’s fellows have also run at Fordham, Stanford, Princeton, Dartmouth, and Yale.

In other places, of course, institutional enthusiasm is harder to measure. The OpEd Project founder Katie Orenstein is keenly aware of the conundrum. “Many of the institutions we work with are owned by or exist to serve the public - whether they are nonprofits which exist for the benefit of the public (like Yale), or state schools funded by taxpayers (like Texas Woman's University),” she says. “And yet, the culture of academia is such that the institutions that exist to cultivate knowledge and the very people who have made it their life's calling to pursue knowledge, are not always rewarded and indeed may be penalized for sharing their ideas with the public.” Says Tristan Bridges, a professor of Sociology at SUNY Brockport who co-authors a column called Manly Musings with CJ Pascoe at Girl w/Pen, “What I think is most fair to say is that they allow it, as long as you're keeping up with all of the other expectations. And they may even like it, but I think they just don't know how to systematically evaluate it - or to understand that it might be good for a small school like mine to have some public scholars. The benefits are not institutionalized in any way.”

They should be. And so, too, should our public conversations about scholars debating in public better acknowledge crossover work, and the ways those engaged in it are already breaking that public/academic binary down, bringing students and faculty together across disciplinary boundaries, and bringing academic publishing up to date.

In our public conversation about the pleasures and dangers of participating in public conversation, let’s not overlook the stories of those who are making it work, and the fact that some institutions are acknowledging it as work. May the fact that we’re having this conversation be an early sign that this slow and uneven thaw might accelerate. At the very least, we’ll keep fanning the flames.

I invite you to follow me on Twitter @deborahgirlwpen, join my Facebook community, visit www.deborahsiegelwrites.com, or subscribe to my quarterly newsletter to keep posted on upcoming workshops and offerings, writings, and talks.