You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

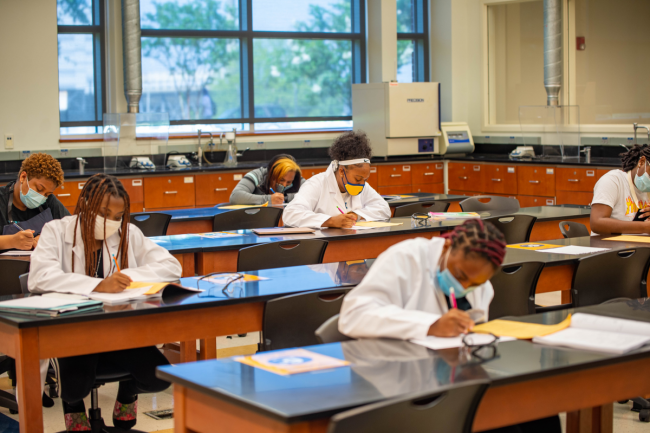

North Carolina A&T

University and college administrators are clearly having a tough time monitoring the daily activities of students during the pandemic, much less controlling their risky behaviors on weekends. This was evident in the parties and other gatherings widely documented on social media during Labor Day weekend and the subsequent spikes in COVID-19 outbreaks on campuses across the country.

This was not the case at North Carolina A&T State University, a historically Black institution where, in a first, classes were held on Labor Day.

“We held classes to discourage our students from going anywhere," Todd Simmons, associate vice chancellor for university relations, said matter-of-factly -- and unapologetically.

The plan appears to have worked. NCA&T had no reported large student gatherings or parties during that time. And after scouring various social media sites, campus officials determined students were largely compliant with a raft of public health rules being strictly enforced on and off the Greensboro campus.

Classes will also be held next month during what was traditionally a short fall break held after midterm exams. Simmons said he heard not a peep of pushback from students.

"I think they thought it was worth the trade-off" of being allowed back on campus and keeping the university open, he said.

NCA&T, like the majority of other historically Black colleges and universities, is very protective of its students. HBCUs tend to have stricter social rules than most other colleges and often exert more control over student behavior -- administrators refer to it as "more hands-on guidance." Many HBCUs prohibit freshmen from living in coed dorms, for instance. Some of the institutions still enforce rules that prohibit students from having overnight guests of a different gender in their dorm rooms. HBCU students accept this standard as a given in normal times; they've generally acquiesced to the new, even stricter, normal of the pandemic.

HBCU administrators are partly banking on the traditional values of their institutions to help keep COVID-19 infection rates down and protect the health of students, faculty and staff. College leaders are also hoping it will help them keep their campuses open after being hit hard by the financial fallout of the pandemic. Several predominantly white institutions, or PWIs, had to shut down their campuses within days of the start of their fall semesters and switch to remote instruction after major outbreaks of COVID-19. No HBCUs with in-person semesters have yet done so.

Total coronavirus infections eclipsed 1,000 at several public North Carolina colleges last week even as some HBCUs in the state were still reporting numbers in the double digits. While the affected institutions are larger than the HBCUs, the HBCU leaders say the size differences are not enough to account for the significant differences in infections and outbreaks.

"Our students may be coming to A&T and to other HBCUs with different mind-sets and different expectations about what college means," Simmons said. They come knowing "that the stakes are high and the opportunities to transform their lives are enormous. That may mean they are more ready to police themselves with regard to COVID protection, and that could be an important reason why our campuses are not experiencing big clusters or outbreaks."

NCA&T (at right) is the largest HBCU in the country and one of five public HBCUs that are part of the University of North Carolina system. (There are also five private HBCUs in the state.) NCA&T reported just eight new positive COVID-19 cases (five students and three employees) between Sept. 11 and 17. Just 62, or 2.7 percent, of 2,320 students and employees who were voluntarily tested since July 1 have tested positive.

NCA&T (at right) is the largest HBCU in the country and one of five public HBCUs that are part of the University of North Carolina system. (There are also five private HBCUs in the state.) NCA&T reported just eight new positive COVID-19 cases (five students and three employees) between Sept. 11 and 17. Just 62, or 2.7 percent, of 2,320 students and employees who were voluntarily tested since July 1 have tested positive.

"It has been very manageable, very low," Simmons said of the numbers.

With Black people dying at disproportionate rates from COVID-19 and communities of color experiencing harmful social and economic consequences, HBCU students have more than a passing familiarity with the heavy emotional and personal costs of the pandemic. Some students have lost loved ones to the coronavirus. Others saw their parents lose jobs as a result of the recession or may have been laid off themselves, and they and their families are now struggling financially. The pandemic has also worsened equity gaps in higher education.

Add to that the widespread national protests this summer against police killings of unarmed Black people -- as well as the antagonistic and sometimes violent response of the Trump administration and police departments -- and the deep pain and anger it has caused. These events have prompted HBCU students to want to return to their close-knit campuses, where they feel nurtured, protected and unified at a time when many of them feel under attack.

Even as other colleges saw enrollment declines, especially of undergraduate students of color, several HBCUs, including NCA&T, are experiencing enrollment increases. There are 11,131 undergraduates enrolled at NCA&T this fall, up 3.9 percent from last year, when undergraduate enrollment was 10,709. (Graduate enrollment also increased, bringing the university's enrollment to 12,754 from 12,556 last year.)

"Our students are different because they’re facing two different threats, COVID and the racial reckoning," Simmons said. "They are constantly seeing that play out, and they don’t know if the government has their back, so there's a higher premium for them to protect themselves and each other to ensure they don’t fall victims to illness or violence."

Brenda Claire Caldwell, president of the Student Government Association at NCA&T, agreed with that assessment.

"I think some of it is the HBCU culture," she said. "We're just like a community, and we want to keep our community safe. We know that Black and brown communities have been affected by COVID and some of us have had family sick from it. And we know we're going to go back to our vulnerable communities, and I think this motivates us."

Elizabeth City State University, another public HBCU that is part of the North Carolina system and that serves mostly rural students from low-income backgrounds, also had increased enrollment this fall. It went from 1,773 students in fall 2019 to 2,002 this fall, with 771 living on campus.The 13 percent enrollment increase was partly due to the university's low tuition -- $500 per semester for in-state students, $1,000 for out-of-state. It is one of three institutions in the UNC system with significantly reduced tuition.

"What we have found is that our students want to be here," said Karrie G. Dixon, Elizabeth City's chancellor. "They don’t necessarily want to be online, and research has shown that they do better with in-person instruction."

Dixon said she regularly walks the campus since the semester began on Aug. 11 and talks with students to gauge "if they were feeling any anxiety or fear about being here. To my surprise, all the ones I spoke with were very positive. Several said, 'Chancellor, please don’t send us home.' I told them, 'I will not have to send you home if you do what you're supposed to do and hold each other accountable and make sure everyone is doing the right thing -- wash your hands, wear your mask and social distance.'"

A United Negro College Fund survey this summer of 5,138 undergraduates enrolled at 17 private HBCUs across the country found that 80 percent of students, particularly first-year students, preferred "to return to campus for some level of in-person instruction" this fall.

"The data reinforced how much these campuses are true communities and villages that are raising their students through their postsecondary education," said Brian Bridges, vice president for research and member engagement at UNCF, which supports 37 private HBCUs. "The colleges offer more than just online or in-person instruction -- they're a safe haven."

Those sentiments were echoed by students surveyed and quoted in the report, which did not identify the students or the institutions they attend. Over and over they described in stark details the difficulties of attending college remotely last semester and why they wanted to get back on campus.

"It was hard to juggle school work with a very sick family member and the drama of what this country is going through," said one student quoted in the report. "Being at [INSTITUTION] gives me somewhat of an escape from this reality."

"It's been an emotional roller coaster for me. [Three] of my cousins contacted [COVID-19] in New York and one passed away from it," said another student who added that an uncle had also died from natural causes, as had a grandmother, for whom the student did not give a cause of death. "It was hard at first dealing with the deaths, but now that I have had time to relax and get my mind off things I'm doing better. I'm just ready to go back to school."

Other students described "the stress of trying not to get sick, not getting killed by police or finding a way to pay for school" and feeling "frustrated and upset" because "COVID-19 [is] out here killing us and so is the police."

"We know Black students are suffering financial and mental distress, and when you combine that with the racial reckoning, they are doubly stressed," Bridges said. He also noted the widely reported lack of regular or reliable internet and Wi-Fi access by students of color from low-income backgrounds or those who are first-generation college students.

Part of the reason so many HBCU students feel more comfortable being on their campuses is the notion of personal and collective fortitude that is heavily promoted at HBCUs and undergirded by the histories of the institutions themselves and the legacy of slavery, violence and racial injustice in the United States. The students are constantly reminded that they are part of larger, common purpose to uplift and be responsible to the larger Black community.

Harold L. Martin, chancellor of North Carolina A&T, said even as HBCUs have held fast to their proudest traditions, some of the institutions, including NCA&T, let go of some of the more dated and conservative customs as they tried to address students' more current, pre-pandemic needs and focus on becoming more innovative and global institutions. But the pandemic allowed HBCUs to more easily revert to their more conventional ways, he said.

"There is this sense in HBCU communities of a great level of expectation for students and engagement with them," Martin said. "But we've had to shift away from some of our traditional types of structures and rules and show more flexibility over time on issues that are much more relevant, especially today. But there's a lot of carryover that this virus is having, a lot of impact on Black and brown communities, and the students are genuinely trying to act more responsibly in this moment."

Swimming Over Sinking

"In times of crisis, you have to embrace the moment," said Quinton T. Ross Jr., president of Alabama State University, a public HBCU in Montgomery, a city known for its important role in the civil rights movement. "We're going to either sink or swim. We choose to swim."

Ross expected total enrollment at his university "to be way down" this semester because of the pandemic. He budgeted for a projected 4,000 students before the pandemic but dropped that number to 3,967 after the pandemic was declared. To his surprise, 4,048 students enrolled this fall, a 3.4 percent drop from the 4,190 enrolled in 2019, but still more than he expected. (Freshman enrollment fell by 6.3 percent, to 954 students from 1,018 enrolled in fall 2019.)

Ross said 36 to 38 percent of Alabama State's students take their classes fully online, while the rest take a mix of in-person and online.

Every member of campus was required to be tested for the coronavirus two weeks before the start of the semester on Aug. 17.

Alabama State has a rapid testing machine that provides results in 20 minutes. Ross said the university will continue to do sentinel surveillance, or random group testing on campus throughout the semester. He declined to reveal the positivity rate. He said the university also purchased 5,000 masks, more than "enough for every member of the campus" and provided every student with "Hornet Packs" that included masks, hand sanitizer and wipes, and a thermometer.

"It's a culture shift, but we wanted to do everything that we could to mitigate the risks on campus," he said.

Ross is optimistic his university will weather the pandemic.

"We didn't do all this preparation to shut down," he said. "Even in this time of crisis, we have to deliver teachable moments for how to rise to an occasion for those things that will be tossed at you in life. I have been pleased with the level of compliance by our students. It's not at all lost on me that students are going to get together, but the thought of at least adhering to the masking, keeping yourself clean, social distancing … Our student leaders have embraced all these things and are on board on student safety and have been helping drive it."

Ross said he asked student leaders to organize virtual events during welcome week. They also organized socially distanced sip-and-paint events and held Greek fraternity and sorority step shows with mask-wearing steppers, of course. The closeout event for welcome week was an outdoor comedy show, which students watched in socially distanced lawn chairs. It was hugely popular, but it created some problems.

The crowd grew larger, and even though the students wore masks, they got too physically close to one another, Ross said.

"I did have to send out a notice to remind them of the rules," he said. "The note admired them but also admonished them."

NCA&T also ran into problems during welcome week but quickly got things under control, Simmons said.

"We continue to be pleased with how disciplined our students are being and that they are avoiding situations that can put them and others at risk," he said. "We’ve gone to extreme lengths to do this."

That includes the decision to formally open the campus on July 1 starting with an extended welcome week. Rather than the two-day orientation program normally held for new students and their parents, the university combined it with move-in week and required students to remain until the fall semester formally began on Aug. 19. The second week was reserved for returning students to move in on staggered days and hours to accommodate spacing. They were also required to stay for the start of the semester.

NCA&T reserved a residence hall to quarantine students. The building has capacity for 200 students, but administrators have restricted capacity to 98 to ensure additional social distancing. Just five students, all asymptomatic, were housed there as of Sept. 15. (Only students who live on campus are required to quarantine in the designated building.) The building is staffed with security guards round the clock that control access to the building, Simmons said.

As necessary as these proactive steps were, efforts to prevent community spread of the coronavirus could not work without the cooperation and support of the students, said Martin. They not only police themselves but also try to influence each other by posting reminders on the university's social media platforms that staying virus-free is a group effort.

Planning and Worrying

Martin was already working with counterparts in the UNC system and its leaders on a pandemic action plan long before students returned to the campus.

“We worked on guiding principles to reopen our institutions in late 2020 and started developing contingency plans,” he said. “We also operated in expectation that infections would peak in mid-June and subside in the early to late July. All our plans were contingent on this.”

A different picture began to emerge as infection rates began surging in North Carolina and other southern states over the summer.

“It began to cause for me a great level of concern about bringing back our students and expecting our employees to be on campus in a potentially unsafe environment,” Martin said. “I was concerned with those most at risk. We have a number of mature faculty members and employees that are providing care to elderly parents. We also have new, young faculty hired over the last five years with children at home.

"All those things weighed heavily on my mind, and I expressed those concerns during our meetings as we talked about the unknowns about the virus and our ability to get testing done in an affordable fashion and to have the provisions in place to have the right campus environments," he said. "This increased my anxiety about opening."

As the start of the fall semester drew closer, Martin also worked with other NCA&T administrators on reopening plans. They decided early on to adjust the academic calendar and nix the Labor Day and fall breaks, which would also help shorten the semester and allow it to end by Thanksgiving.

They enlisted a cadre of people to help in the effort. Fraternities and sororities, student government leaders, managers of off-campus apartment complexes, local party promoters, and others were all part of the plans put in place.

“We contacted the leaders of our fraternities and sororities and pulled them into conversations about the dos and don'ts and the expectations we had,” Martin said. “There were those who thought they would have private parties off campus, and promoters in the community who prey on university students and hold these kinds of events, but we met with and developed a strategy in partnership with all the apartment complex managers in the area where our students live in private housing and developed a plan to prevent that from happening. We asked them to report any instance of student gatherings and to call our campus police department to disperse them, and to share the names of student violators.”

“We said, these are the governing expectations around gathering, social distancing and mask wearing and made it very clear to them that we expected them to adhere to them and that there would be consequences if they didn’t adhere.”

Martin also met with the chiefs of the campus police, the Greensboro Police Department and the university system police.

"We all agreed that we would suffer the same outcome if we don’t work together," Martin said.

Still, there were blips.

A group of about 75 first-year students gathered outside near the university’s clock tower during welcome week in keeping with an unofficial custom started by students five years ago, after the tower was built.

Student affairs staff were quickly dispatched to break up the gathering, and the university’s social media manager followed up with a gentle tweet:

“We get it. We know that college provides a time for social engagement and exploration, but our current situation has changed things a bit. #NCAT remember the privilege of campus life for now, means: Masks are required. Unfortunately, large gatherings just cannot happen.”

Upperclassmen also weighed in social media.

"We said, 'Please, for the sake of all of us, let’s not do that anymore,'" said Caldwell, the SGA president.

The freshmen responded with comments such as, "Y'all don’t understand, y’all got to have a first-year experience. If that was y'all’s freshman year, y'all would be doing the same thing," Caldwell said. "Most upperclassmen were like, 'We don’t think we’d be doing the same thing. You have to remember that this is a pandemic and you’re not going to have a regular freshman year or experience.'"

Practicality won the day. The upperclassmen schooled the newcomers about the rules of engagement in the pandemic era.

Caldwell, who is in her senior year, said she and her classmates saw the videos on social media of UNC Chapel Hill and North Carolina State University students partying in the first weeks of the semester and then saw their campuses abruptly shut down. "We don’t want that to happen here," she said. "We’d like to stay on campus as long as possible."

Simmons, the vice chancellor, said most students understand the university shares this goal, and that's why the "we get it" tweet was widely retweeted and liked.

“Message heard and definitely received,” he said. The students got a pass.

“We gave them some grace and showed some understanding since it was their first time on the college campus,” Simmons said. “But we made clear that we can’t have this happen again.”

It did happen again -- a group of roughly the same size with a mix of students gathered outside the student center a week later. Student affairs and university relations staff, accompanied by campus police and security guards, descended and broke up the gathering. This time there was no gentle tweet.

Simmons said the students were told in no uncertain terms that if they gathered again, they would individually “be referred to the student disciplinary process and we will deal with you harshly.” Repeat offenders would “be charged criminally for flouting the governor's executive order and escorted off campus,” he said, noting that the charge is a misdemeanor.

The last thing Caldwell wants is for infection rates to increase and for the campus to close because of students being reckless. Returning home would not be a major inconvenience -- her family lives just 10 minutes away from the campus -- but she loves living on campus and wants to be there now more than ever.

The lives lost to the pandemic and to police abuses of power "just [make] us want to be there for each other and hold each other up," she said. "Having to see people that look like us dying or being killed makes us want to take care of each other even more."

Ross, the Alabama State president, is witnessing the same thinking among students on his campus.

"Shelter in time of a storm, this is what our HBCUs offer," he said. "There's the mental health factor and what all of this is doing to them. We are that place that helps them understand their place in all of this, and their place in the world, and that also gives them the tools to pivot and to adjust to all of this as they go out in the world."