You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Pexels.com

Graduate programs are struggling to support students whose lives and research have been upended by COVID-19. Many students now need more time -- and funding -- to finish their dissertations or rethink them entirely. One solution? Suspending or reducing Ph.D. program admissions for fall 2021, to conserve resources for current cohorts.

Suzanne Ortega, president of the Council of Graduate Schools, said that between the effects of COVID-19 on university budgets and continued uncertainty about the future, “it’s very difficult to predict what graduate school admissions and enrollment will look like for 2021.” Some universities are giving individual programs flexibility as to the size of their cohorts, however, she said.

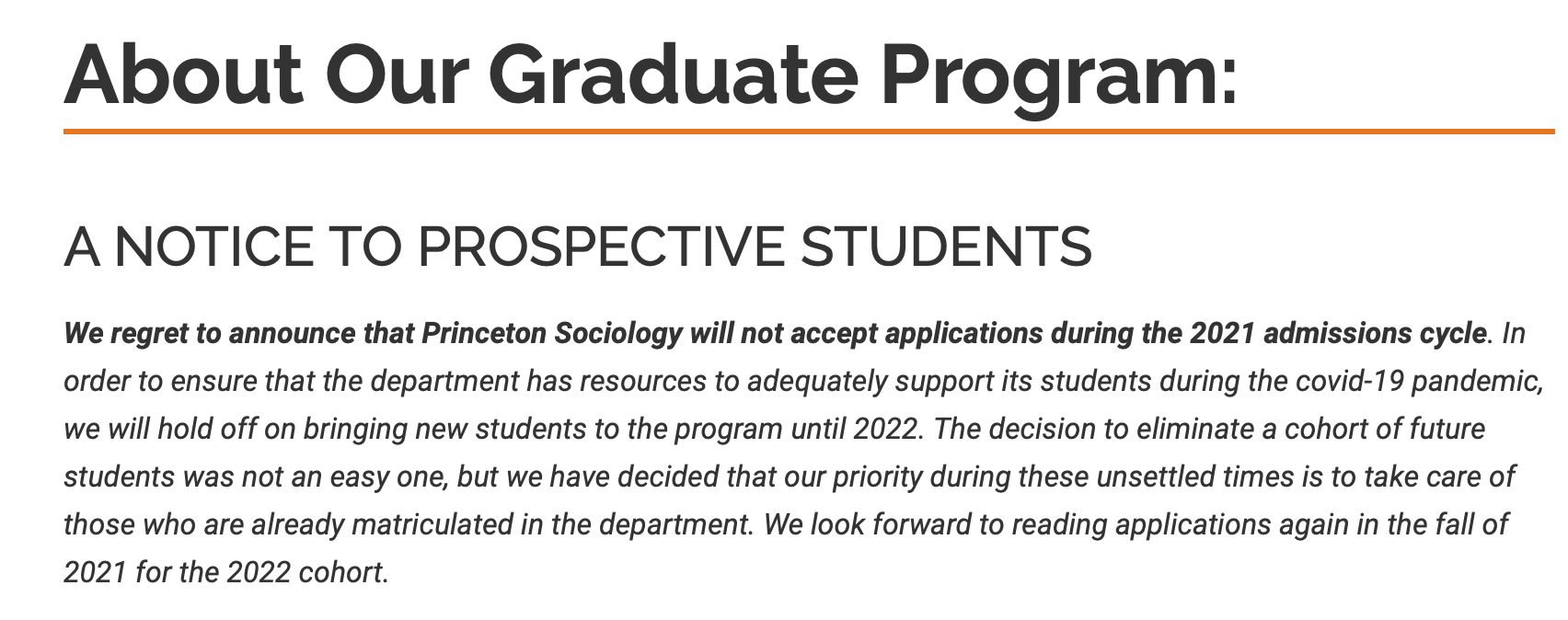

Case in point: Princeton University’s sociology department recently announced that it will honor admissions offers to students for the coming academic year but postpone further admissions until fall 2022. After conferring with each other and current Ph.D. students, the department’s faculty voted unanimously to hit the pause button.

“We’re not happy about having to do this,” said Dalton Conley, Henry Putnam University Professor of Sociology at Princeton and director of graduate studies in the department. “But we’d rather focus on taking care of students we’ve already brought into the Princeton community rather than the theoretical idea of students who potentially might come.”

Students are currently guaranteed six years of funding if they successfully hit certain milestones through year five. Skipping a cohort could help the department fund Ph.D. candidates who have clearly been affected by the pandemic beyond that time frame, into their seventh year. Supporting fewer students over all may also allow the faculty to offer training in switching research gears, if necessary, and on social distancing-compatible methods such as digital ethnography and computational sociology.

New York University’s sociology department, meanwhile, has a tentative plan to reduce Ph.D. cohorts from nine students to six for three years, starting in 2021. The hope is to free up enough internal fellowship funding to offer third- and fourth-year Ph.D. cohorts another year of funding, to make up for time lost during the pandemic. Fifth years will be eligible for another semester of funding, if the department’s plan is approved higher up the university chain.

Similar conversations are happening elsewhere, even if they haven’t been made public yet.

Ortega said graduate programs often make decisions about cohort size by “balancing the funding needs of current students so they can complete their degrees with the university mission to provide access to high-quality graduate education for future students.”

Iddo Tavory, associate professor of sociology at NYU and the program’s director of graduate studies, said his department “actually considered completely canceling a cohort, but we felt that we have to balance our commitment to students with our commitment to actually allowing people to pursue Ph.D.s.”

The department also floated the idea of offering graduate students additional, need-based funding. Tavory said students generally opposed this notion, arguing that it could pit them against each other and that need may be hard to quantify. And so the department agreed on what he called a “hybrid model” of reduced admissions for three years.

Similarly, Princeton considered limiting cohort sizes for two years before making what Conley called the “bolder” choice to suspend.

“Worst-case scenario would be planning on small cohorts and then going back and having to cancel,” he said, adding that Princeton sociology can also preserve the “community” that comes with bigger cohorts. This year the department admitted 14 Ph.D. applicants, and 11 committed.

Sociology likely represents the first wave of COVID-19-related 2021 admissions news because original research in the field so often involves interviewing or observing human research subjects, including those in other countries. All of that contact and travel has been affected by COVID-19; some departments have dramatic tales of extracting students from faraway field sites before international borders closed in March.

“Sociology as a field is particularly notable, or more likely to be affected by the virus than others because of the nature of our work,” Conley said. At the same time, he said, “This is what we study -- dynamic social systems. There’s significant risk that things are going to get worse, and so this is a proactive approach to buffer students from that.”

Princeton sociology anticipates the change will have little to no impact on undergraduate instruction, in which graduate students serve as precepts, or teaching assistants. Pausing admissions in a larger institution might have clearer effects on undergraduate teaching, though.

Balancing Funding Woes With the Need for More Social Scientists

Gwen Chodur, director of social justice concerns at the National Association of Graduate-Professional Students, said that graduate programs “have a financial obligation to their students and they do need to be mindful of that, especially in times like these.” Nevertheless, she said, citing the Princeton decision, “we as an organization are concerned about the priorities of a university that would make such a decision while sitting on a $29 billion endowment.”

A university’s “fundamental mission is to educate and train students,” she said, and it can’t “advance that mission without students.”

Michael Hotchkiss, Princeton spokesperson, said that graduate school administrators are working with departments on how to help students though the pandemic, including by “trading” admission slots for a corresponding amount of funding to support continuing students whose research has been impacted by COVID-19. Each department makes its own decisions in the end.

As for concerns about suspending admissions at institutions with big endowments, Princeton president Christopher L. Eisgruber said in a recent campus memo, “Princeton spends more than $1.3 billion from its endowment every year, including in years where endowment returns are negative. We spend at a rate such that, absent growth, the entire endowment would be gone in 20 years.”

Karin Knorr Cetina, Distinguished Service Professor and chair of sociology at the University of Chicago, said she thought Princeton’s move was a "wonderful gesture" that should help its students considerably.

Chicago changed its own graduate admissions model prior to the pandemic, so that starting officially in 2022, internally funded graduate students will be financed for the duration of their programs, in exchange for program caps. Programs with shorter timelines will get to admit new students faster.

In any case, Knorr Cetina said, her department doesn't need to find money to fund students for a sixth or seventh year, as it's "already financing students routinely not just for five but for seven years."

Ed Liebow, executive director of the American Anthropological Association, said he hadn’t heard of Ph.D. programs in his field suspending admissions. Several other scholarly associations in the humanities and social sciences said the same. Austerity measures thus far have targeted faculty positions, Liebow said, though cuts in some places have implications for graduate programs.

Asked if suspending admissions was advisable, Liebow said he doesn’t envy administrators who have to plan ahead amid so much uncertainty, “and I imagine they are looking under the sofa cushions for all the pennies they can save.” Still, he said, “the longer-term impacts of eliminating a whole cohort of incoming students need to be taken into account, and frankly, from my perspective, we need more social scientists in training, not fewer.”

If the pandemic has demonstrated anything, Liebow said, it’s that “in the absence of safe and effective vaccines or medical treatments, the main way of disrupting the infectious disease transmission dynamic is through changes in behavior and institutions to achieve greater distancing and shielding.” Training in disciplines such as anthropology and sociology “is absolutely essential in bringing rigorous, evidence-based research on how to promote healthy behaviors, prevent disease and reduce the institutional barriers that sustain the gaping disparities in access to adequate health care.”