You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

A Virginia state agency has released what is likely the first broad look at the mid-career earnings of college graduates, with a newly released report tracking wages at all degree levels for up to two decades after graduation.

The new data from the State Council of Higher Education for Virginia advances the large and growing amount of proof that college pays off, at least for graduates. It includes wages for students who earned associate, bachelor’s and doctoral degrees in the state in 1993, also comparing earnings across disciplines.

The overall trend lines were good for graduates as they reached the middle of their careers.

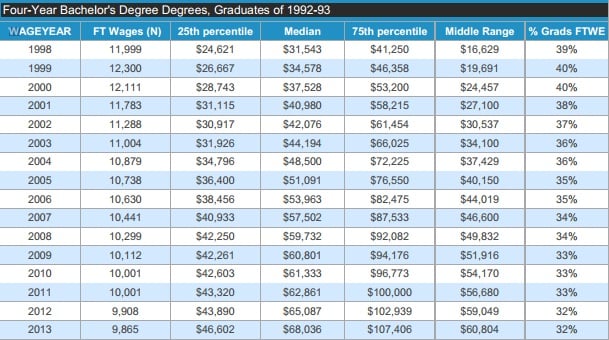

For example, the report found a median annual wage of $68,036 for bachelor’s degree holders in 2013. That amount was more than double their median earnings of $31,543 in 1998, when graduates were five years out of college.

Most previous attempts to track the wages of graduates look only at earnings a few years after they complete college. That can skew the way policy makers and consumers view the value of various types of degrees, because longer career arcs differ across disciplines.

One common argument is that while a degree in the liberal arts looks like a bad bet right after graduation, at least from an earnings perspective, those with those degrees probably catch up over time. That’s because students who get a broad education in the humanities often later go to graduate school or work their way up to lucrative positions in sometimes-surprising fields.

The council’s new report goes farther than most studies by taking the long view. But it found those assumptions about the liberal arts not to be true.

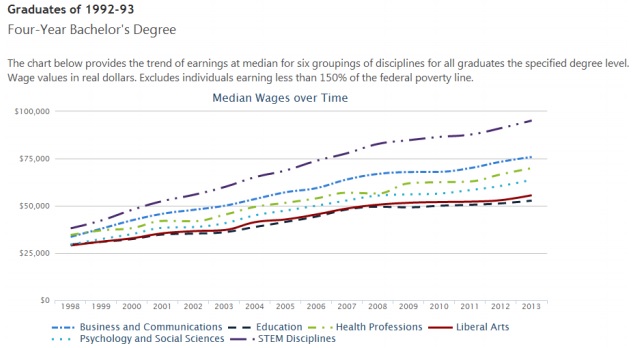

Bachelor’s-degree-holders in engineering, computer science and engineering technologies had the highest wages over time. They out-earned their peers with the lowest-paying degrees -- education, English and visual and performing arts -- right after college. And the gap didn’t close after two decades.

The data showed similar results, for the most part, across degree levels. Technical and professional disciplines tend to lead to higher wages than the liberal arts and humanities.

The data showed similar results, for the most part, across degree levels. Technical and professional disciplines tend to lead to higher wages than the liberal arts and humanities.

However, the council warned against reading too much into those results. The study did not include data for individual institutions and programs, in part because of concerns about oversimplification and a rankings-style approach to seeing which colleges fared best.

The data builds on a 2012 study by the council that looked at earnings of graduates 18 months and five years after college. In contrast, that report did include information about specific Virginia colleges and programs. The project was a joint venture of the council and College Measures, a nonprofit group that the American Institutes for Research (AIR) supports.

“These reports are not meant to project earnings for new graduates or to place values, specific or comparative, on given credentials,” the council said in the summary report for the new data. “Instead they are meant to describe the trajectory of earnings for past graduates to provide greater understanding of the possible impacts of funding decisions on higher education and education-related student debt.”

It would be a mistake to use the new report to tell students not to major in the liberal arts, said Tod Massa, the council’s policy research and data warehousing director. For starters, liberal arts degrees actually did well in the earnings data.

“Those incomes aren’t that bad,” he said. For example, visual and performing arts majors were near the bottom in 2013 median wages, but they still earned $51,414.

There are factors to consider other than earnings when considering a discipline, Massa said, such as job satisfaction. And too often people focus on the median when looking at wage data. Individuals matter, he said, and can have wildly different outcomes within even one program at a single college.

For example, the report found a growing range in wages as time passed, with the difference between the first and third quartiles of earners more than tripling.

“There are so many of us who don’t apply to the median,” said Massa, a veteran researcher and higher education expert. “I have a degree in studio art and painting.”

'Fact-Based Evaluation'

The new data sets can be combined with information on student and graduate debt to create better models on the funding and cost of college, the report said. One possible area, Massa said, should be in understanding how to design income-based loan repayment programs.

Other states could follow Virginia’s lead, said Massa. Since 1993 the council has been collecting student-level data from all the state’s institutions -- public and private alike. It carefully scrubbed any identifiers of individual students, he said, to protect their anonymity.

Earnings information in the report comes from the Virginia Employment Commission, which provided unemployment wage files from 1998 to 2013. (As a result the first five years of graduates’ earnings are not part of this report.)

The report’s overall findings mirror those of several influential studies that Georgetown University’s Center on Education and the Workforce has produced.

That research has found that occupational choice can trump degree level in earnings, as people with less education in high-paying occupations (like computer science) can out-earn graduates with more education in less lucrative career paths. However, degree level still matters most within individual occupations.

Virginia’s community colleges offer two general types of associate degrees -- those for students who plan to transfer to a four-year institution, or applied science degrees that are more technical.

Virginia’s community colleges offer two general types of associate degrees -- those for students who plan to transfer to a four-year institution, or applied science degrees that are more technical.

Holders of associate degrees in applied science tend to earn the most shortly after college, according to the council’s previous study. But the new report found that the difference between the medians of the two types of degrees “essentially disappears” after 20 years.

One reason, the report said, might be that some of the transfer-degree holders later completed a bachelor’s degree and saw a corresponding bump in income, which in turn increased the median for that type of associate degree.

The report raises as many questions as it answers. Massa calls it a “fact-based evaluation of what happens with college graduates.”

Context is crucial in making sense of the wage data.

For example, the median household income is $64,000 in Virginia, according to the report. That means individual bachelor’s degree holders from the class of ’93 are out-earning most households. But even that analysis benefits from more detail, as the report notes that the relatively high wages of Northern Virginia drive up the state’s median wage, which is much lower in other parts of the state.

Massa has written previously about peoples’ fascination with college rankings. He said those tools are popular in part because they are easy to understand. But “policy deserves something more than easy.”