You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

The most independent and self-motivated students entering college are more likely to expect they will take a fully online course as undergraduates, a new survey says, but the vast majority of students still connect higher education with the traditional residential experience.

The 2013 Freshman Survey, conducted by the University of California at Los Angeles’s Cooperative Institutional Research Program, suggests that more than two-thirds, or 69.8 percent, of entering freshmen are using online instructional materials such as massive open online courses and video lectures on their own time, compared to less than half, or 41.8 percent, as an assignment in a high school class.

Cash Is Still King

The impact of rising costs in a post-recession economy on the concerns and decisions of incoming freshmen is stronger than ever, an annual survey shows. Read more.

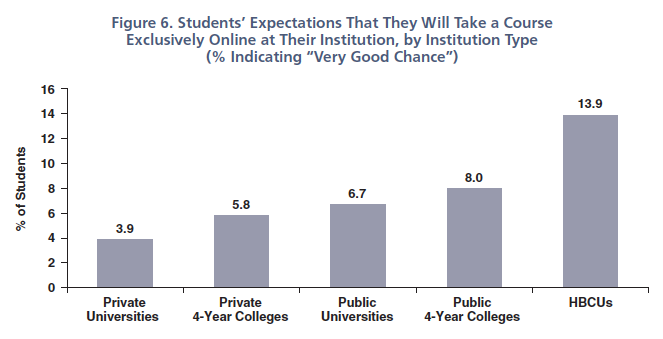

Yet once they reach college, the expectation that fully online courses will be a part of the schedule plummets. Less than one in every 10 students in the fall 2013 freshman class at almost every type of four-year institution said there is a “very good chance” they will enroll in a fully online course. Students at private universities are least likely to think so -- only 3 percent of respondents at those institutions picked that answer -- but the interest isn’t much higher at public four-year colleges, where 8 percent of students said the same.

Kevin Eagan, interim director of the institute's Cooperative Institutional Research Program, attributed the lack of interest in online courses to the specific slice of higher education -- recent high school graduates going off to college -- covered by the survey.

“These are the traditional-aged students who are more likely to live on campus and have an expectation of a more traditional or idealized college experience based on what they've seen on television, film and perhaps what their parents have experienced,” Eagan said. “I also think that once students get into college and find that courses are impacted -- or they're capped because they are so popular ... their perceptions may change.”

Oddly, students at historically black colleges and universities were most likely to think that a fully online course is in their academic future, clocking in at 13.9 percent. HBCUs have been slow to adopt online education, and Eagan said the finding “may just be an odd artifact of the data.”

But Roy L. Beasley, who has previously charted the landscape of online education among HBCUs, said the numbers may be plausible. If that's the case, he said, the findings point to an even greater disconnect between student expectations and the programs HBCUs offer.

"Unfortunately, at this time and for the foreseeable future, the expectations of (black) students at the 106 HBCUs, i.e., the number of online course that they would like to take, will greatly exceed the capacity of most HBCUs to deliver," Beasley said in an email.

The students most interested in fully online courses were, not surprisingly, those who frequently used online instructional materials as high school seniors. More than a quarter of those students said there was at least “some chance” they would take a fully online course in college. Those students were also more likely to “exhibit behaviors and traits associated with academic success and lifelong learning,” the report states.

The 2013 edition of the survey marks the first time the CIRP has asked students about their online education habits, and Eagan said it will be interesting to see how the trends develop over time. For now, there is no trend data to explain how the growth of MOOCs and other forms of online education may have affected how students interact with academic materials online.

"Colleges and universities -- some of them have jumped on the MOOC bandwagon, if you will, but students, at least in this year's data, haven't done so," Eagan said. "They're still having the expectation that they're going to have face-to-face interaction in a brick-and-mortar classroom with their faculty."

Of course, expectations don’t always line up with reality, as some former entering freshmen have realized. In last year’s survey, 84 percent of those surveyed said they thought they could graduate in four years, even though roughly 50 percent actually do, Eagan said.

Allie Grasgreen contributed to this report.