You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

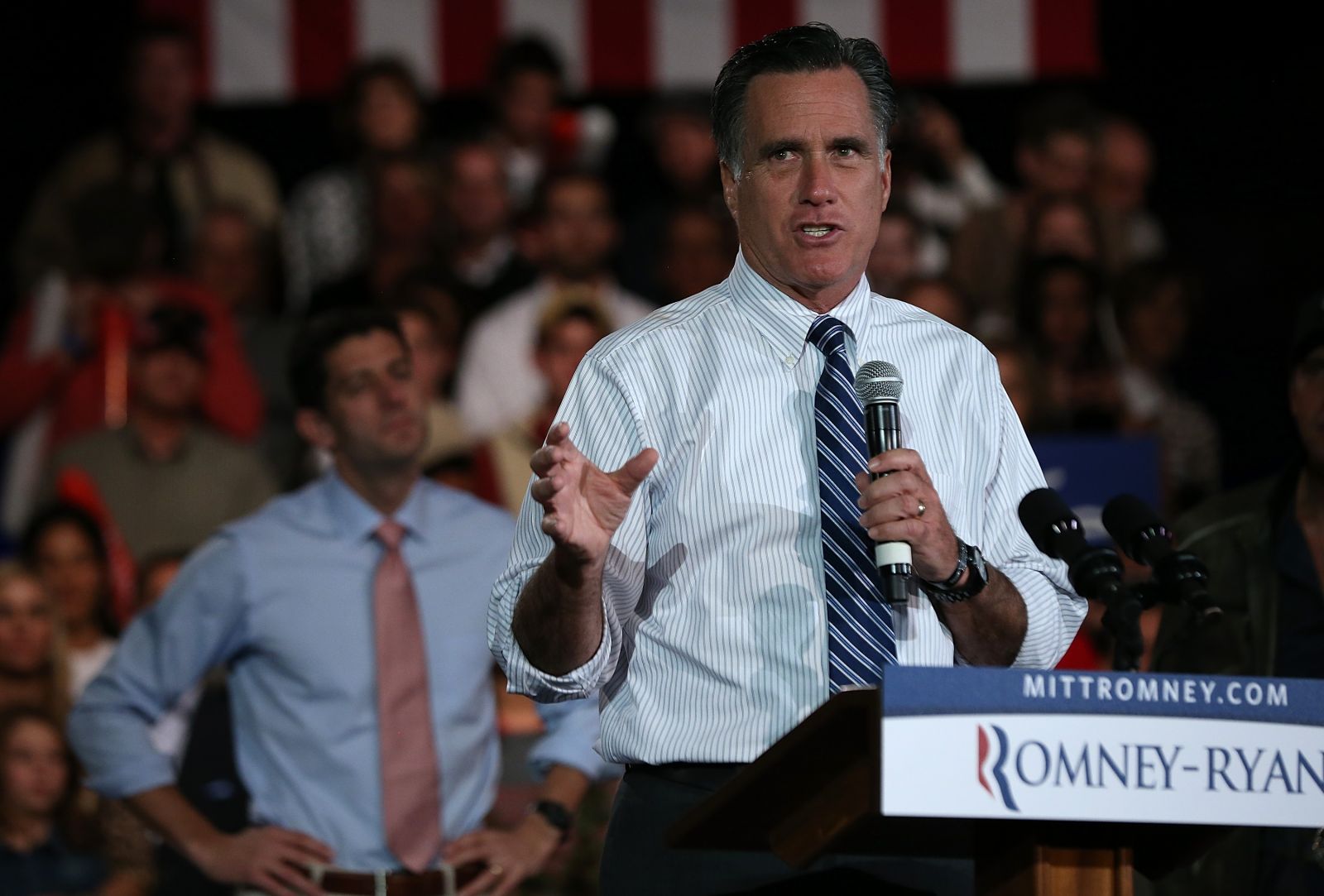

WASHINGTON -- For a few days in early June, as President Obama and Republican Mitt Romney sparred over student debt and interest rates, it seemed that higher education might play a major role in the 2012 presidential race.

Since then, it has largely faded into the background, the subject of occasional T.V. and radio advertisements or debate one-liners. Still, when voters go to the polls on Nov. 6, issues important to colleges and their students -- some obvious, some less so -- will hang in the balance.

Either Obama or Romney will confront fiscal challenges that could profoundly affect financial aid and research, and have the opportunity to shape policy on a range of issues -- from labor relations and immigration to Title IX and for-profit colleges -- and reshape the higher education landscape. Since many expect Congress will remain divided, making it difficult to pass major legislation, much of that is likely to happen through regulatory changes.

Fiscal Policy and the Pell Grant

Looming even before Inauguration Day is the “fiscal cliff”: on Jan. 2, deep, mandatory spending cuts will go into effect and many tax breaks will expire. The budget cuts, known as sequestration, are the consequence of Congress’s failure to reach a long-term debt deal in the 14 months since the vote to increase the nation’s debt ceiling.

Sequestration would cut deeply into many programs dear to colleges and universities. While the Pell Grant Program is exempt from the mandatory cuts, nearly everything else is not; other federal grant programs, as well as research spending, would take an 8.6 percent cut. If and how the mandatory budget cuts, which slice defense as well as domestic spending, might be averted is uncertain, although both Republicans and Democrats have said that finding a solution is a priority. “It will not happen,” Obama said of sequestration at the third presidential debate.

Any solution will have to come from Congress, and a long-term budget deal could cut Pell Grants and other programs, though probably not as deeply as the mandatory cuts would.

Presidential influence and priorities can be key in these negotiations -- a fact made clear by the fate of the Pell Grant over the past few years. When Republicans regained control of the House of Representatives in 2010, the grants were often proposed as a candidate for deep cuts in budget disputes. The Obama administration made preserving the maximum grant its top priority, sacrificing some student loan interest benefits and accepting eligibility changes for the grants in exchange for keeping the grant at $5,550, the level to which he pushed it by prioritizing the program in his budget plans and stimulus initiatives.

Even if Congress reaches a deal in time to avert the cuts, sequestration is only the first of several hurdles confronting federal financial aid programs in the coming months. The debt limit will need to be increased again in 2013, and, especially if Obama is re-elected, Congressional Republicans could demand deep spending cuts in exchange.

The government’s two main sources of aid for low-income students, Pell Grants and subsidized student loans, face crises of their own in 2013. The interest rate on subsidized student loans, on which the government pays the interest while students are enrolled in college, is scheduled to double to 6.8 percent in July. And in October, when the next fiscal year begins, Pell Grants face a funding shortfall.

The government’s two main sources of aid for low-income students, Pell Grants and subsidized student loans, face crises of their own in 2013. The interest rate on subsidized student loans, on which the government pays the interest while students are enrolled in college, is scheduled to double to 6.8 percent in July. And in October, when the next fiscal year begins, Pell Grants face a funding shortfall.

The Obama administration has made its position on the grants clear over the past four years: preserving the maximum grant is a top priority, and cuts to less direct benefits, such as student loan interest subsidies, are preferred if cuts have to be made.

How a Romney administration would deal with the Pell Grant’s challenges is less obvious. The former Massachusetts governor’s running mate, Representative Paul Ryan, is the author of a budget plan that most agree would slash the maximum grant by making deep cuts to domestic spending. (The plan doesn’t specify which programs would be cut.) In an education white paper over the summer, Romney called for shrinking the program; during the presidential debates, he changed course, saying he expects that the program will continue to grow.

The white paper, the most comprehensive education plan from the Romney campaign, called for refocusing the grants on the truly needy -- implying further eligibility changes.

But in the first education debate, Romney changed course: “I’m not going to cut education funding,” he said in response to an accusation from Obama that his budget plan could require a 20 percent cut to education. “I don’t have any plan to cut education funding and grants that go to people going to college. I’m planning on continuing to grow, so I’m not planning on making changes there.”

He repeated the points in later debates, saying he wanted to preserve education funding and expected continued Pell Grant growth, though how that could be done while implementing the overall budget cuts in his plan has remained unclear.

One other likely change to federal student aid policy could happen under either administration. Congress, largely with the Obama administration's consent, has nibbled around the edges of subsidized loans each time it makes a change to federal student aid. First subsidized graduate loans were eliminated; next was the grace period for subsidized loans to undergraduates. As the Pell Grant remains under financial pressure, an outright elimination of subsidized student loans -- redirecting the savings to grant programs -- seems a real possibility, one even a few Democrats have supported.

Student Loans, Debt & Campus-Based Aid

While student debt hasn’t played a significant role in the campaign since the summer -- fading in tandem with the Occupy movement -- Obama has promoted his proposed changes to the government's income-based repayment program. If he is re-elected, his administration has said, the government will decrease monthly student loan payments under the program, which helps financially strapped borrowers repay their loans, and forgive loans sooner. Romney, who has said he is opposed to loan forgiveness, seems highly unlikely to keep those changes.

Romney has also proposed a change to campus-based programs as part of an overall simplification of federal financial aid -- perhaps folding the Supplemental Educational Opportunity Grant in with Pell Grant funding, changes a Romney education adviser, Scott Fleming, mentioned in broad terms during an appearance before the National Association of Student Financial Aid Administrators in July.

Obama, too, has proposed major changes to the campus-based aid programs -- expanding their funding in order to use the money as a carrot, or a stick, on college pricing. Whether either approach would succeed is unclear. While some sectors of higher education, particularly community colleges, would favor a reorganization of the campus-based programs -- which are clustered at more established public and private colleges -- the colleges that benefit from them (and their allies in Congress) are likely to fight changes from either Obama or Romney.

The federal student loan program could change in other ways under a Romney administration. Obama has boasted on the campaign trail of his overhaul of the program in 2010. Passed as part of the health care legislation, the changes ended federally guaranteed lending in which banks and other lenders made student loans with government money, and switched entirely to direct lending, in which the government makes the loans itself.

Because of how student loans are accounted for in the federal budget, the switch saved billions of dollars, some of which were directed toward an expansion of the Pell Grant. In recent months, pressure has increased, especially from Republicans, to change the way the government accounts for loans on its books. "Fair-value accounting" takes into account market risk -- the likelihood that a loan won't be paid back -- and, under that system, student loans still look profitable, but much less so, according to a June report from the Congressional Budget Office.

A switch to fair-value accounting was included in Representative (and now vice presidential candidate) Paul Ryan's proposed budget for fiscal year 2013. If it goes through, Romney may have a greater chance of pushing his own changes to the student loan program -- switching away from all direct lending to a system that includes private entities again, because it would appear to be less costly than it would under current accounting rules. Continuing reports that direct loans are plagued with servicing problems could also be used to support a case for changing the system again.

Changes to the Pell Grant have frequently happened through the budgetary process, and the Obama administration laid out its plans for income-based repayment through executive order and negotiated rule-making. But more sweeping changes to campus-based aid or student loans, including both candidates’ proposals, would need to go through Congress, probably as part of the Higher Education Act, which is up for renewal in 2013.

That law governs federal financial aid and, by proxy, many aspects of college and university policy. Few believe Congress will reauthorize the act on time, given the more pressing crises it must face (and the fact that the law’s elementary and secondary education counterpart has been overdue for renewal since 2007). Still, the next president will oversee at the very least the first serious moves toward extending the act, if not a complete overhaul.

Whether a Romney administration would demand more from colleges, in addition to the proposed changes to federal financial aid, is unclear. But the Obama campaign has already put forth proposals that would increase the federal government’s power over campus policies, especially tuition. Though they might handle it differently, neither administration is likely to go easy on colleges in terms of accountability; given that ever-rising tuition has created questions about quality and value, those days have passed.

Obama has promised to uphold tighter regulations of for-profit higher education in a second term, which observers say would likely prolong the sector's current woes. A Romney administration, however, would help get for-profits back to growth through less regulation.

The Obama administration pioneered its regulatory approach to higher education at for-profit colleges, and the sector gives some of the sharpest examples of the differences between the two candidates on higher education policy. The Obama administration moved swiftly to regulate those colleges, which have witnessed rapid growth in recent years, most notably through its “gainful employment” rule.

The rule applied to vocational programs at colleges across all sectors, but were considered aimed at for-profit colleges. It cut off federal financial aid after three years of high default rates or debt-to-income ratios for graduates.

The rule applied to vocational programs at colleges across all sectors, but were considered aimed at for-profit colleges. It cut off federal financial aid after three years of high default rates or debt-to-income ratios for graduates.

For-profits have fought bitterly against the rules, and problems with one aspect of gainful employment -- using a repayment rate of at least 35 percent as one of three ways to measure whether graduates have found work -- led a federal judge to invalidate the government's mechanism, though not its underlying goals and purpose. While Romney has been largely silent on for-profit colleges (after an endorsement of one, Full Sail University, drew scrutiny and some derision in January), his education advisers have criticized the rules as overly punitive and unfairly singling out one sector, and have said for-profits’ contributions to higher education are important. In September, an adviser told The New York Times that Romney would repeal the gainful employment rule.

The Obama campaign also hasn’t devoted much time to for-profit colleges on the trail or in its future plans. A change to rules governing how much of a college’s income can legally come from federal financial aid -- right now, 90 percent, but many lawmakers and groups who favor tighter regulations on for-profit colleges would like that number to be lower -- could be included in the next reauthorization of the Higher Education Act.

Most proposals for further regulation have come from Senate Democrats (especially Senator Tom Harkin, who conducted a two-year investigation into for-profit colleges), not from the Obama administration. The focus in future years is likely to be on colleges that serve veterans. Most new bills in the Senate deal with colleges, especially for-profit colleges, that receive money from veterans' programs like the Post-9/11 G.I. Bill.

Regulations on ‘Value’ and Student Loans

Observers have summed it up this way: a Romney administration would impose less regulation, but provide less support for financial aid and other programs colleges care about. An Obama administration would continue increased federal generosity toward colleges and universities, but would accompany that approach with more regulatory strings attached.

At the financial aid administrators’ conference earlier this year, Fleming, the Romney education adviser, drew spontaneous applause when he said a Romney administration would try to reduce the regulatory burden on colleges. Which regulations he’d repeal were unclear, but a prime target would be the credit hour and state authorization rules.

Those rules give a federal definition of a credit hour -- which many colleges see as federal intrusion into academic matters -- and require that colleges get approval from every state in which they enroll students in online courses. A bill to overturn both passed the House with a bipartisan majority earlier this year, but has stalled in the Senate. Since then, the Education Department has quietly stopped enforcing the state authorization requirements, which have also been overturned by courts.

Regulation of other sectors related to higher education would likely ease under a Romney administration as well. The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, which is playing a growing role in examining and regulating private student loans, has been a focus of Republican criticism since it was created as part of new Wall Street regulations in 2010. The bureau has collected complaints and suggested new regulations for private student loans. Romney hasn’t said exactly what he would do with the agency, but would either move it outside the Federal Reserve (lessening its powers) or break it up entirely, an adviser told The Wall Street Journal in May.

Romney and his education advisers have advocated for disclosure as a substitute for regulations, saying putting data (such as default rates) before the public would let market forces reward good actors and punish bad ones without the government getting involved. Public and private nonprofit colleges often draw little distinction between the two, in part because they find disclosure requirements alone to be onerous; when the Obama administration put forward a proposed “shopping sheet” for colleges and universities, a suggested rather than required disclosure, financial aid administrators complained that it was emblematic of the administration’s “one size fits all” approach.

But disclosure requirements are only part of an aggressive regulatory agenda Obama has put forward for his second term, a policy shift signaled by his State of the Union speech in January. In that speech, Obama put colleges and universities “on notice”: if they cannot stop tuition prices from rising, he said, they will get less federal financial aid. At the Democratic National Convention in September, he quantified the effect he said his policies would have: cutting the rate of increase in college tuition (4.8 percent for sticker price, according to a new College Board report) in half over the next decade.

Whether his approach would work at all is disputed; that colleges and universities will fight any attempt to try it and find out is a near-certainty. The plan involves an overhaul of campus-based financial aid, as well as a $1 billion “Race to the Top” competition for higher education in an attempt to shape state policy and, through maintenance-of-effort requirements, forcing states to continue funding higher education. Most controversial, though, is measuring colleges not only by their price but by whether they provide “good value” -- a measure that, to many in higher education, smacks of the same approach the administration has taken with for-profit colleges.

Other differences in approaches to regulation switch predictably as control of the White House changes hands. Chief among them, perhaps, is the National Labor Relations Board, which, as new presidents appoint different representatives, flip-flops on who in private higher education should be allowed to unionize, and under what conditions.

The issue is particularly salient this year because of two higher education cases pending before the board. It has reopened a decision made in 2004, under George W. Bush, that disallowed graduate student unions at private universities. (Unionization at public universities is governed by state law.) Traditionally, the board has granted graduate students unionization rights under Democratic presidents, and taken them away under Republican ones; even if the board should decide in the graduate students’ favor before Inauguration Day, a Romney administration could appoint new members to the board who would reverse the decision.

The board is also considering allowing faculty members at private colleges to unionize and collectively bargain, a practice largely blocked by the 1980 Supreme Court case NLRB v. Yeshiva University. Faculty groups have argued in favor of greater unionization, while administrators have largely opposed it. The Obama-appointed majority on the board is seen as more sympathetic to labor, but a ruling supporting unionization at private colleges is likely to be challenged in court before any organizing and collective bargaining can occur.

Romney’s campaign has not addressed unionization in higher education, but House Republicans have said they are concerned over the graduate student and private college cases, as well as opinions from NLRB regional offices that support unionization at Roman Catholic colleges.

Title IX and Affirmative Action

The Education Department’s Office for Civil Rights, like the labor relations board, can abruptly change the volume and tenor of its regulatory approach when a new administration takes office. Such was the case with Obama: in 2010, he promised more scrutiny of whether colleges were living up to federal law on not discriminating based on race and gender.

In higher education, the Obama administration has stepped up efforts to enforce Title IX, which forbids gender discrimination in education programs that receive federal funds. The Education Department has especially focused on sexual harassment complaints at colleges. It reached high-profile settlements with several colleges in harassment cases in 2011, followed by a “Dear Colleague” letter that did not mince words in describing colleges’ responsibilities in cases of sexual harassment or assault. Among the clarifications was a lower standard of proof, the preponderance-of-evidence standard, than the police would use in dealing with such cases.

The administration also issued guidance for how colleges can take race into account when admitting students -- an issue that has become even more central as the Supreme Court considers Fisher v. Texas, a case that could end race-based affirmative action at colleges and universities.

Romney’s campaign has not discussed how it would handle Title IX, nor has it expressed a position on affirmative action (although the Republican platform, highly critical of higher education in general, opposed it). Still, Republican administrations tend to rein in enforcement by the department’s civil rights division compared to Democratic ones. President George W. Bush’s Education Department made it easier for athletics programs to comply with Title IX, a change the Obama administration withdrew.

The past four years have brought little new action on immigration, and it’s unclear whether the next four will either. Obama’s main initiative -- a program to delay deportation and provide a path to legal residency for undocumented young people brought to the United States by parents in the country illegally -- led colleges with high populations of undocumented students to push them to apply. Romney has said he would end the program, although he would honor the deferrals granted by the Obama administration. He supports military service as a path to legal residency for undocumented young people.

The two candidates agree on one policy: granting green cards to foreign citizens who graduate with advanced degrees from American colleges. But that initiative, strongly supported by research universities, has always become entangled in more comprehensive action on immigration in Congress -- where divisions on contentious issues stall any progress.

On research funding, if the mandatory budget cuts in January are averted, little is likely to change. Romney has taken aim at traditional Republican targets, including saying he would eliminate federal funding for the National Endowment for the Humanities. But both candidates support continued funds for basic scientific research, and the issue has not come up on the campaign trail. Still, the Ryan budget or other deep budget cuts would make money for domestic discretionary programs, including research, more difficult to come by.

The stark differences between the candidates’ approaches on many subjects -- especially regulation -- do not mean there aren’t points of agreement. In July, Fleming, the Romney adviser, estimated that the two campaigns agreed on “80 percent” of higher education policy, including the importance of college access and completion.

While Romney is likely to pursue fewer regulations than a second Obama administration, the idea that the federal government should play a role in holding colleges accountable is increasingly shared by both parties. While disavowing the increased regulation of Obama’s term, Romney’s white paper echoed the president’s State of the Union address, saying colleges will no longer get a blank check from the federal government while increasing tuition.

The accountability agenda could take different forms, depending on who holds office, with more or less emphasis on regulation versus disclosure, or measuring students' employability or other outcomes as a prerequisite for federal support. In the same way, the combined efforts of the Obama administration and foundations -- especially the Gates and Lumina foundations, among others -- have ensured that college completion (or "success") will join college access as an overarching federal goal.

What form the next administration's accountability and completion agendas will take is still hazy. But no matter who wins, there is little doubt there will be one.