You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

On Monday Inside Higher Ed published the latest iteration in our series of surveys of college presidents about the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and the recession, offering a snapshot at various points since March into campus leaders' views on how their institutions, employees and students have handled the upheaval wrought by the unprecedented events of this spring. The surveys cover a wide range of issues, including their sense of how effectively their campuses continued to educate students during the emergency pivot to remote learning.

We explored some of those subjects in our article about the survey's results on Monday. But I want to dig a bit more deeply into that topic in today's "Transforming Teaching and Learning" column, and to offer some thoughts about how colleges may be factoring those views into their plans for the fall.

The gist is this:

- Presidents weren't wowed by their colleges' performance in delivering instruction this spring.

- Their worries about how effectively they can teach online, and students' potential dissatisfaction with that learning, are part of what's driving most of them to physically reopen their campuses this fall. (Yes, money is a major factor, too.)

- They may be overestimating their ability to ensure a safe and comfortable physical environment for learning.

***

Let's start with the data on the survey of 97 presidents from four-year public and private institutions and community colleges.

The survey gave presidents numerous opportunities to assess how their campuses did on the learning front this spring.

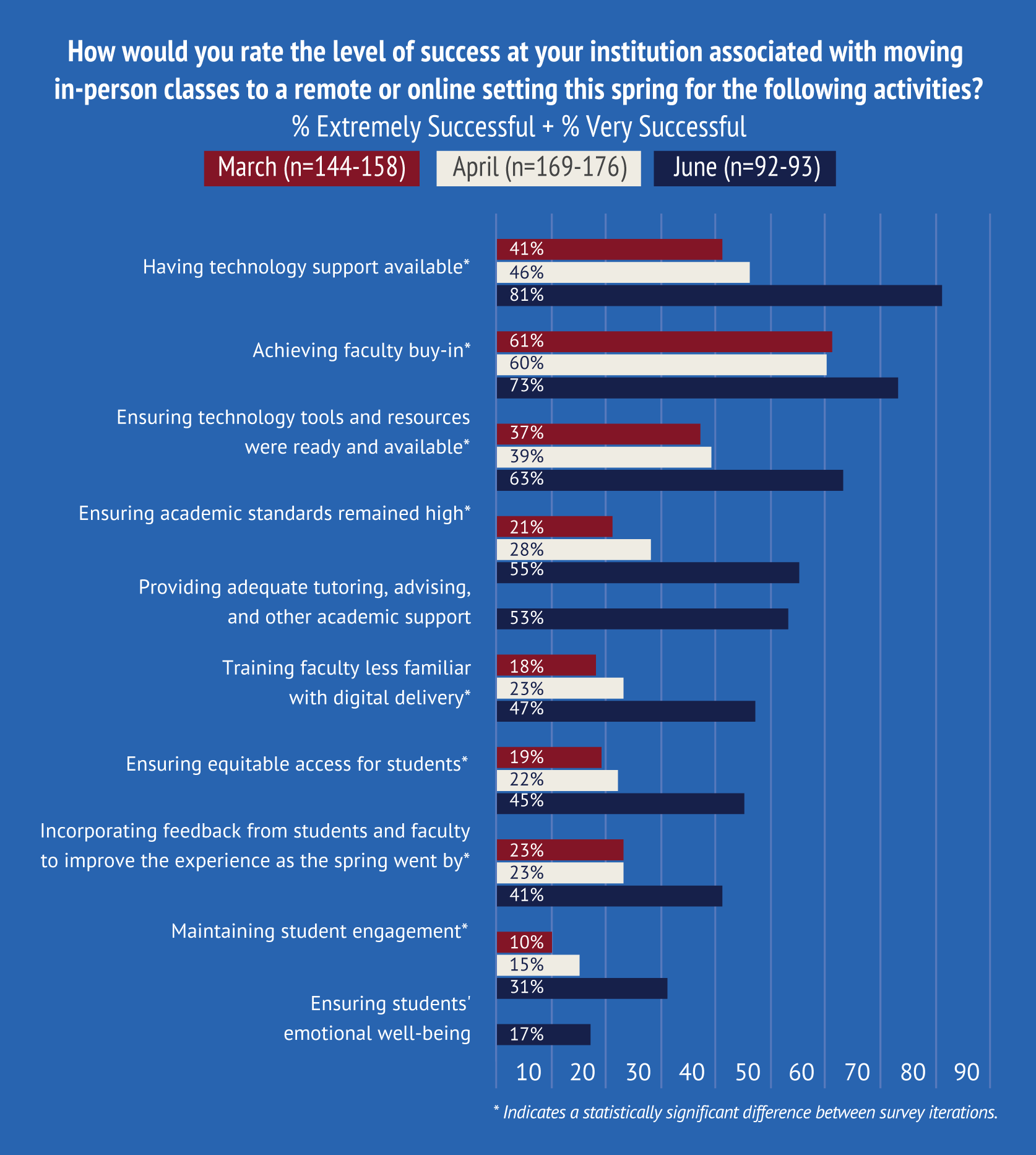

Most directly, they were asked to "rate their level of success at your institution with moving in-person classes to a remote or online setting this spring" on various fronts. The picture looks better to campus chiefs in the rearview mirror than it did in the heat of the moment: on almost every measure, presidents' June ratings were much higher than they were in March and April, in most cases significantly so, as seen in the chart below.

Presidents rated their institutions highest on having technology support available (81 percent said they were extremely or very successful, up from 46 percent in April) and ensuring the availability of technology tools and resources (63 percent extremely or very successful, up from 39 percent in April).

They also gave their colleges good marks on achieving "faculty buy-in" (73 percent), although they graded themselves lower on their success in "training faculty less familiar with digital delivery," which only 47 percent said they did very well. That squares with the commonly held view among students that they had significantly uneven experiences, with some professors doing a much better job structuring and leading remote courses this spring.

More than half of presidents, 55 percent, said they believed their institutions had been extremely or very successful at ensuring that academic standards remained high, though the survey did not ask them to define that.

The presidents' self-reviews were worse when it came to student-facing elements. Fewer than half of college leaders, 45 percent, said they had been extremely or very successful at ensuring equitable access for students, and 41 percent said so about incorporating feedback from students and instructors to improve the experience as spring went on. And just 31 percent gave their colleges top marks on maintaining student engagement, and more presidents (27 percent) said their institutions were slightly or not at all successful at ensuring student well-being than said they were extremely or very successful (17 percent) at that.

The survey asked presidents when they will undo a set of decisions most of them made earlier this spring, and roughly two-thirds said they will undo March's choice to move the majority of in-person courses online by summer (20 percent) or fall (48 percent). Those numbers are consistent with the announcements colleges and universities have been making in recent weeks, with most (currently) planning to bring some or most students back to campus this fall.

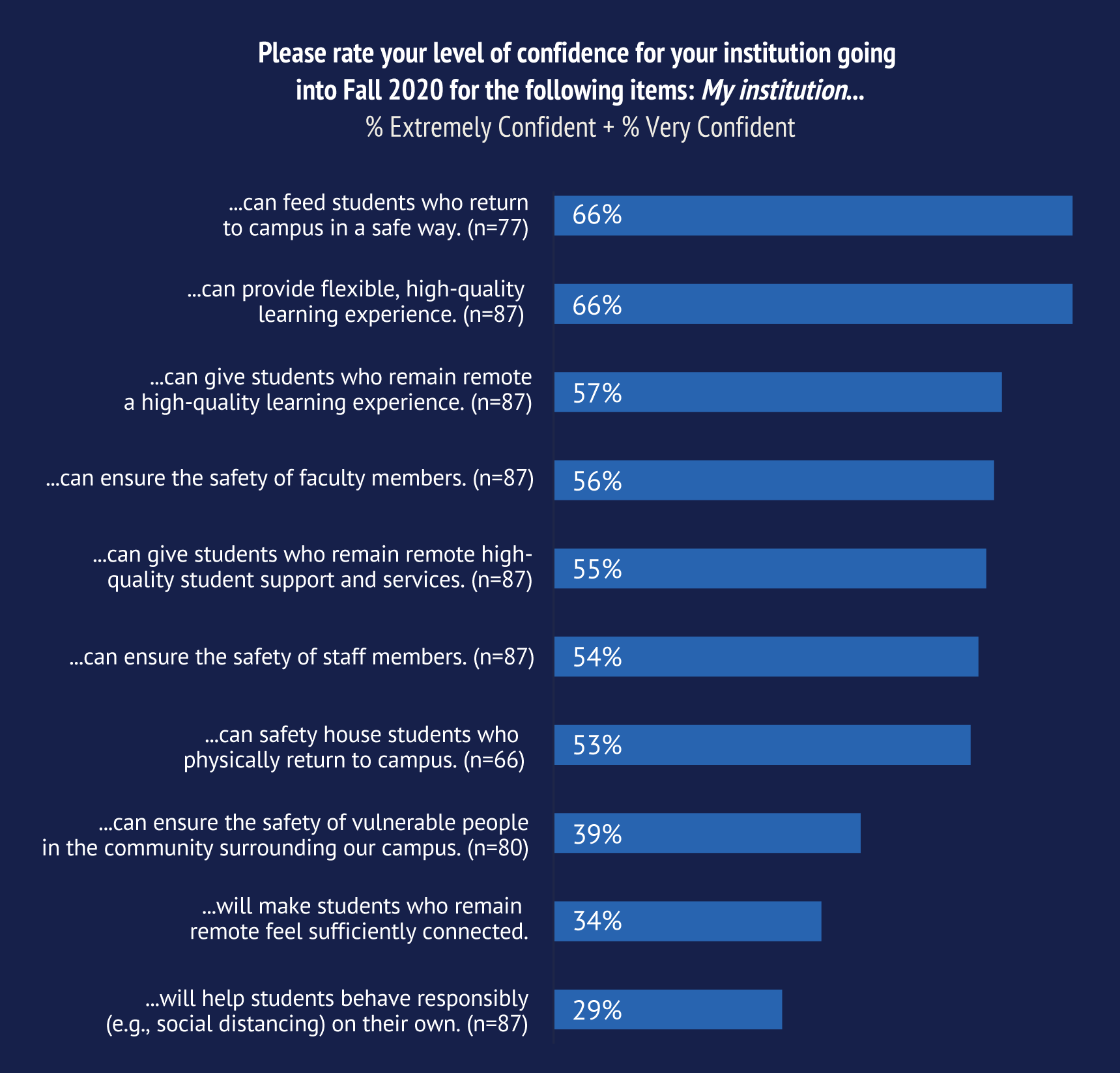

The presidents' mixed reviews of their campuses' performance in pivoting to remote learning this spring probably factor into that choice, but so do their answers to another survey question about their confidence related to certain matters related to the coming fall (below).

Campus leaders seem more confident that they can provide a flexible and high-quality learning experience to students in an on-campus setting (66 percent are extremely or very confident) than that they can ensure a high-quality experience to students who remain remote (57 percent). Even fewer presidents say they can provide high-quality student support and services to remote students (55 percent), and only a third (34 percent) are extremely or very confident that they "will make students who remain remote feel sufficiently connected."

It's pretty clear from the data above that most presidents emerged from the last few months underwhelmed by their institutions' ability to provide instruction to students remotely with little preparation, and skeptical about how much they can improve on it, even with more time and training, this fall.

A few other data points from the survey suggest that they're worried about more than the educational impact of continued dependence on virtual learning, however.

Asked about their biggest concerns going forward, declines in overall future student enrollment (91 percent very or somewhat concerned), inequitable impact on underrepresented students (89 percent) and overall financial stability (88 percent) top presidents' list.

Nearly three-quarters (72 percent) say they are very or somewhat concerned about a "perceived decrease in the value of higher education," up from 60 percent in April and 48 percent in March. Roughly half are worried about demands for reimbursements for room and board (52 percent) and tuition (49 percent).

***

Presidents are not wrong to think, or at least worry, that providing instruction predominantly or entirely online this fall would have a set of potential negative consequences, educationally and financially. We know that remote learning imposes more hardships on certain groups of students (e.g., those who lack internet access or safe and quiet places to study), and that some of those same students benefit most from the full array of student services that most institutions offer better on campus than virtually.

It is also certainly true that many students (and parents) expressed qualms about the perceived quality and engagement of the remote learning they received this spring, and that meaningful numbers said they might not enroll in the fall if their institutions stayed virtual.

And yet … Even putting aside my concern that some institutions are overemphasizing financial and enrollment concerns in their decisions to bring students back to campus, the survey data raise questions for me about whether campus leaders are even weighing the educational factors evenly.

First, college leaders report overwhelmingly that they invested this spring in new online learning resources, which many of them say they will never reverse. Many of them are spending significant time and energy in preparing their faculties this summer better than they ever have for online teaching, and it seems safe to say that the quality of virtual instruction most institutions will offer this fall will be better than the suboptimal version they provided on the fly during the spring. (How much better is hard to say, and of course it will vary from college to college, and from instructor to instructor.)

In addition, survey respondents expressed more confidence that they can educate students in a high-quality way this fall using the in-person and hybrid models most of them are currently planning than by remaining remote. But for most institutions (and many faculty members), hybrid learning will be (yet again) an entirely new experience, and some leading learning experts express reservations about how well that's going to go.

That's especially true if, as seems increasingly likely, colleges are overestimating how many students they're going to be able to squeeze into physically distanced classrooms or how many faculty members are going to feel safe stepping foot in those classrooms, given COVID-19 concerns.

Lastly, the surveyed presidents (rightly) doubted whether they had done a good job engaging students and ensuring their well-being when they educated them remotely this spring.

But are they taking the flip side into account? Are they confident that the drastically altered campuses students would be returning to this fall will be safe and comfortable places in which to learn? Is it possible that the many precautions wise institutions will be taking to keep their physical environments safe will be so different, so unsettling, so anxiety-provoking as to offset whatever learning advantages might accrue from being there in person?

For me the ultimate question is: Are the physical learning environments students might return to going to be better for them than whatever (hopefully improved) virtual learning strategies colleges can develop by the fall?

I'm not convinced the answer is no, but from our survey data, I'm also not sure all presidents are asking and answering the right questions.

***

Inside Higher Ed has stopped posting comments at the end of each article, but I still want to hear from you. Please email me with any comments, critiques, questions or story ideas, any time. You will hear back from me.