You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Istockphoto.com/martinwimmer

It will be some time before we know the full impact of the COVID-19-induced shift to remote learning this spring -- how it altered the arc of students' academic careers, for example, or affected the extent and nature of their learning.

But we now have some early data on how it reshaped instructors' teaching practices.

A survey released today by Bay View Analytics (formerly the Babson Survey Research Group) and its president, the digital learning researcher Jeff Seaman, offers some insights into the transition that virtually all colleges, instructors and students undertook this spring as the novel coronavirus shut down campuses across the country.

The survey largely reinforces, with data, our collective anecdotal impression that higher education has engaged in a wholesale, sudden shift to remote instruction, and that instructors adapted how they go about teaching in the transition.

More About the Survey

This survey was conducted by Bay

View Analytics, in collaboration with

the Online Learning Consortium (OLC),

WICHE Cooperative for Educational

Technologies (WCET), the University

Professional and Continuing Education

Association (UPCEA), the Canadian

Digital Learning Research Association

(CDLRA), and Every Learner

Everywhere. Cengage funded the

study.

On Friday, April 24, Inside Higher Ed

will offer a free webcast in which

speakers from Bay View, OLC and

Warren County Community College

will discuss the results and answer

your questions. Please register here.

The data bring into especially sharp relief, however, the reality that instructors significantly altered their expectations for students and for themselves, changing or cutting back on assignments, lowering their expectations for both the amount of work students do and, to a lesser extent, the quality of that work.

***

The study surveyed 826 faculty members and administrators at 641 American colleges and universities this month, as many institutions began to wind down their instruction for the interrupted academic term. Five organizations collaborated on the survey (see box at right), and Cengage funded it.

Some of the survey's scene-setting results won't be particularly surprising.

It finds, for instance, that the vast majority of institutions (90 percent) engaged in some form of emergency distance/virtual education to conduct or complete the spring term; those that did not were typically colleges that already were exclusively online, or in the few areas in the country where shelter-in-place orders were not in force.

Similarly, three-quarters of instructors (76 percent) reported that they had to move some of their courses online to complete the term. Again, the remaining instructors were those who were already teaching fully online or whose courses were canceled or suspended because of the pandemic.

The administrators surveyed were asked about the level of experience their instructors had with remote teaching before this spring's shift. Half of them (50 percent) said their institutions had some faculty members with online teaching experience to ease the transition. This spring's transition was almost certainly more difficult for the roughly one-third of colleges and universities nationally that offered no or few online courses before this spring. But Seaman notes that many administrators may not "know which of their faculty have online teaching experience," given that some may have done so at other institutions or in previous jobs, "so they may be undercounting this number."

The bulk of the survey's questions focused on understanding how instructors changed their teaching practices and their approach to students.

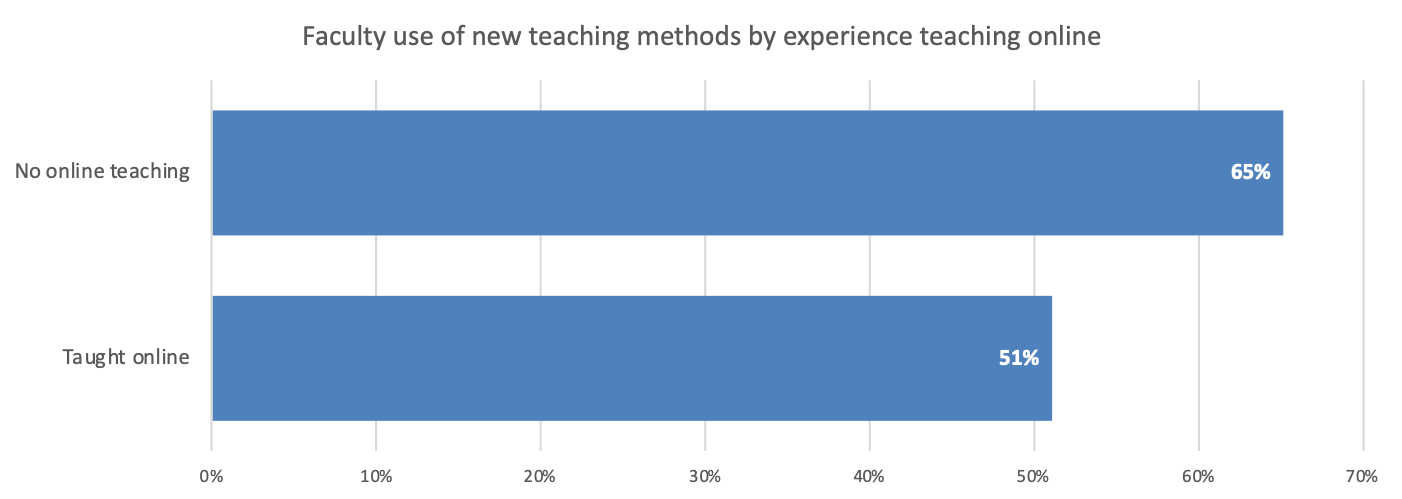

A majority, 56 percent, said they had used "new teaching methods" in transitioning their courses to remote delivery. Instructors with no previous online teaching experience were much likelier to answer that way than were their peers who had taught online before they were forced to this spring.

Asked to list the techniques they used to transition their courses to virtual settings, instructors overwhelmingly cited using their institution's learning management system (83 percent) and utilizing synchronous video technology (80 percent). That's consistent with overwhelming anecdotal reports that many professors, especially those inexperienced in incorporating technology into their teaching, responded to this transition largely by clinging to the familiar -- delivering lectures or holding class discussions with students via webcams.

Smaller proportions, but still majorities, used other forms of video, 65 percent recorded their own lectures and 51 percent said they used videos from third-party sources.

There were a handful of differences in the practices embraced by instructors with and without previous online teaching experience, with experienced online instructors less likely than their peers to use synchronous lectures or discussions and more likely to distribute information using the LMS and to use their institution's conference or chat function to communicate with students.

Perhaps the most interesting -- and possibly controversial -- responses came to a question about how instructors changed their requirements for or expectations of students in the shift to remote learning.

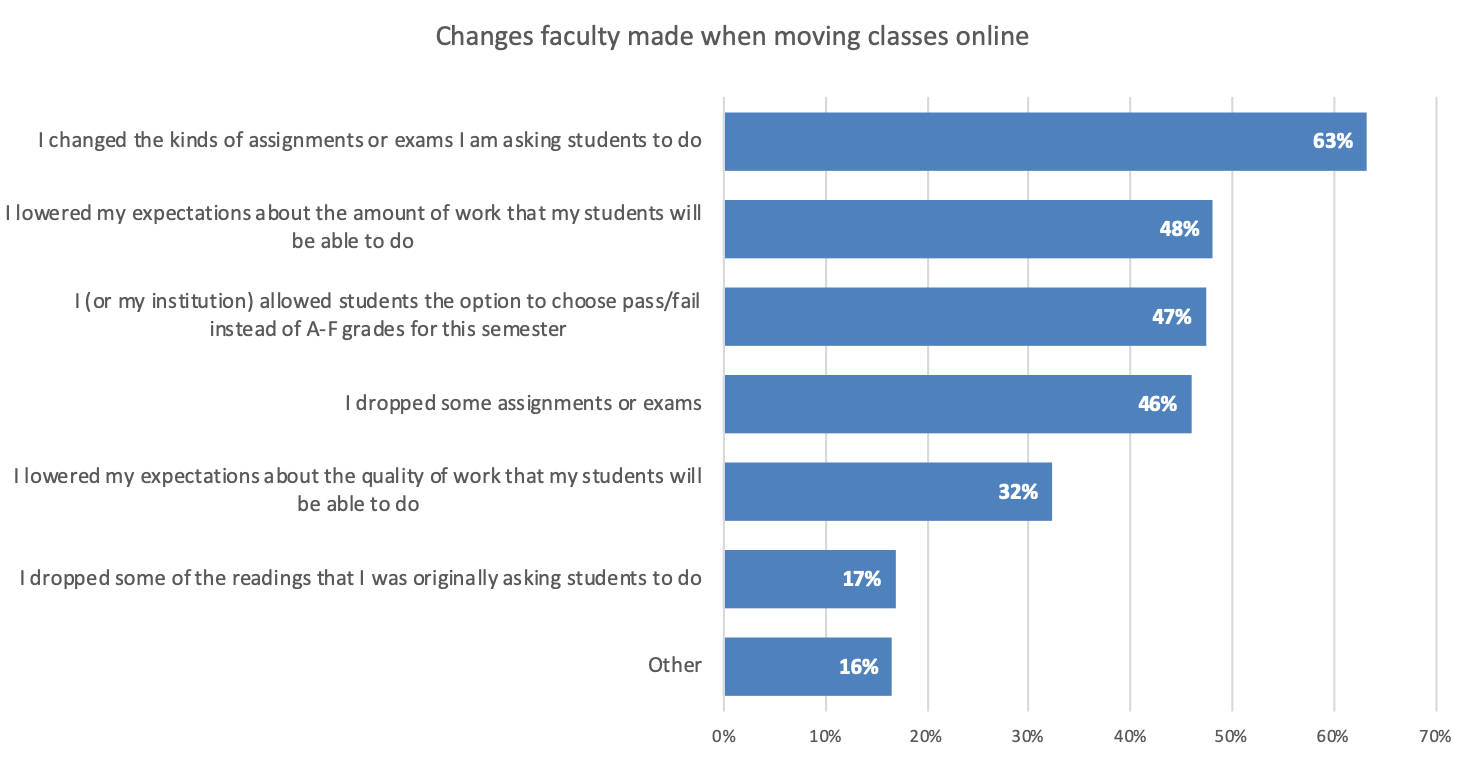

Almost two-thirds said they changed "the kinds of assignments or exams" they gave to students, and nearly half said they lowered their expectations for the amount of work students would be able to do (48 percent), made it easier for students to take their courses pass/fail (47 percent), and "dropped some assignments or exams" (46 percent).

Relatively few, 18 percent, said they "dropped some of the readings" they had originally expected students to do.

But almost a third -- 32 percent -- said they had "lowered the expectations about the quality of work that my students will be able to do."

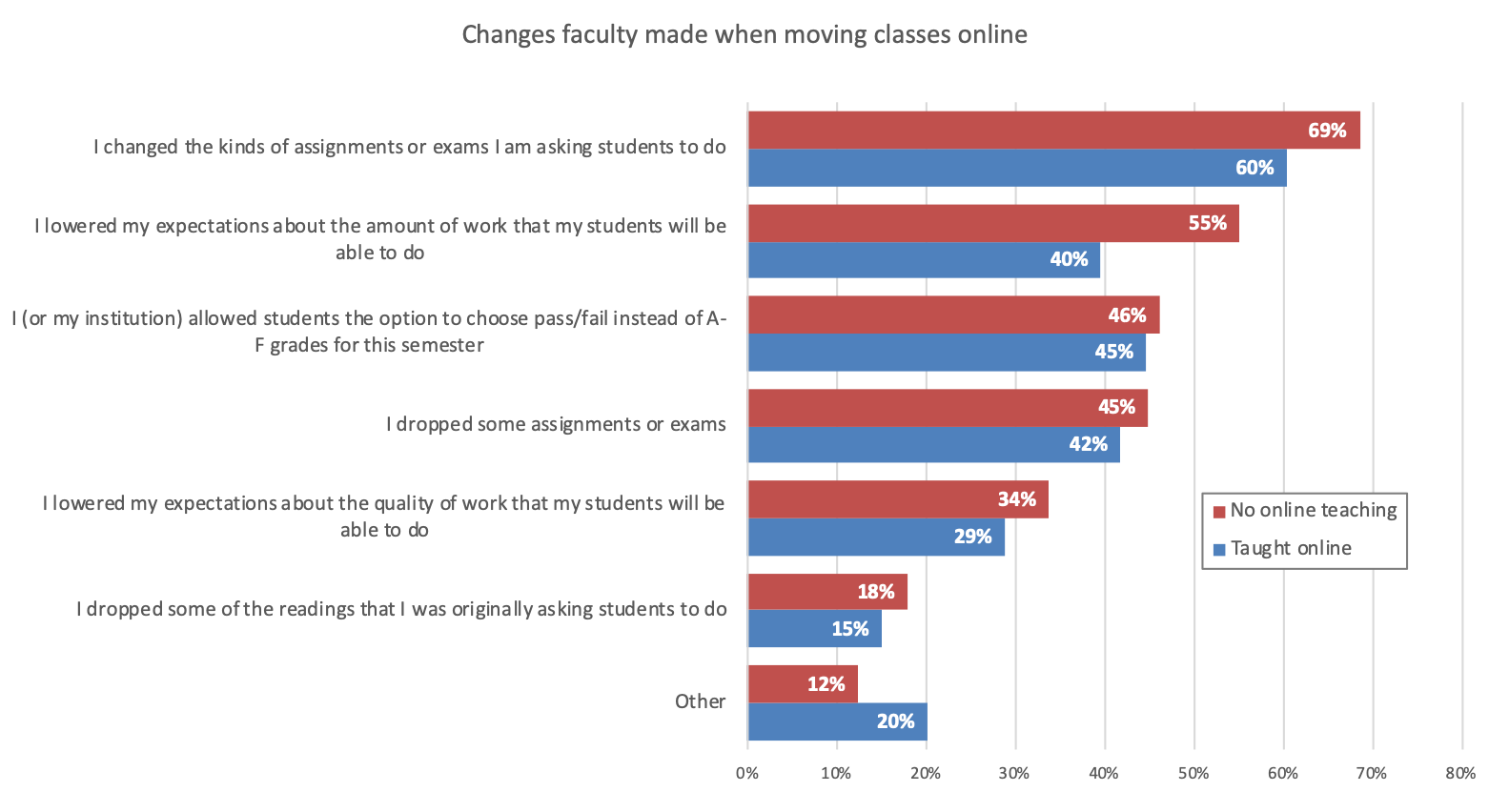

Instructors with and without previous online teaching experience had roughly similar views about their expectations for students, with a couple of exceptions. Most significantly, instructors with previous online experience were 15 percentage points less likely than their peers to lower their expectations for how much work students could do, and somewhat less likely to change the nature of their assignments to students.

Faculty members at community colleges were far less likely than their peers to report that their students had been given more flexibility on pass/fail options -- 22 percent compared to 53 percent and 54 percent at four-year public and private colleges, respectively.

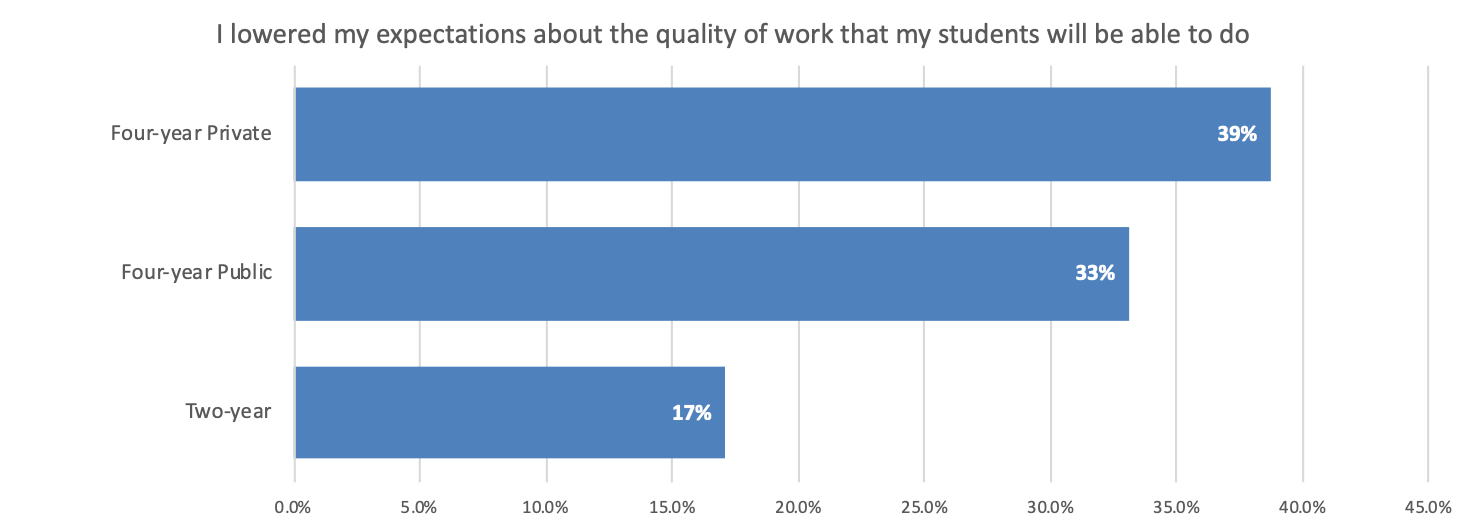

Two-year-college instructors were also half as likely as their peers to say that they had lowered their expectations for the quality of student work.

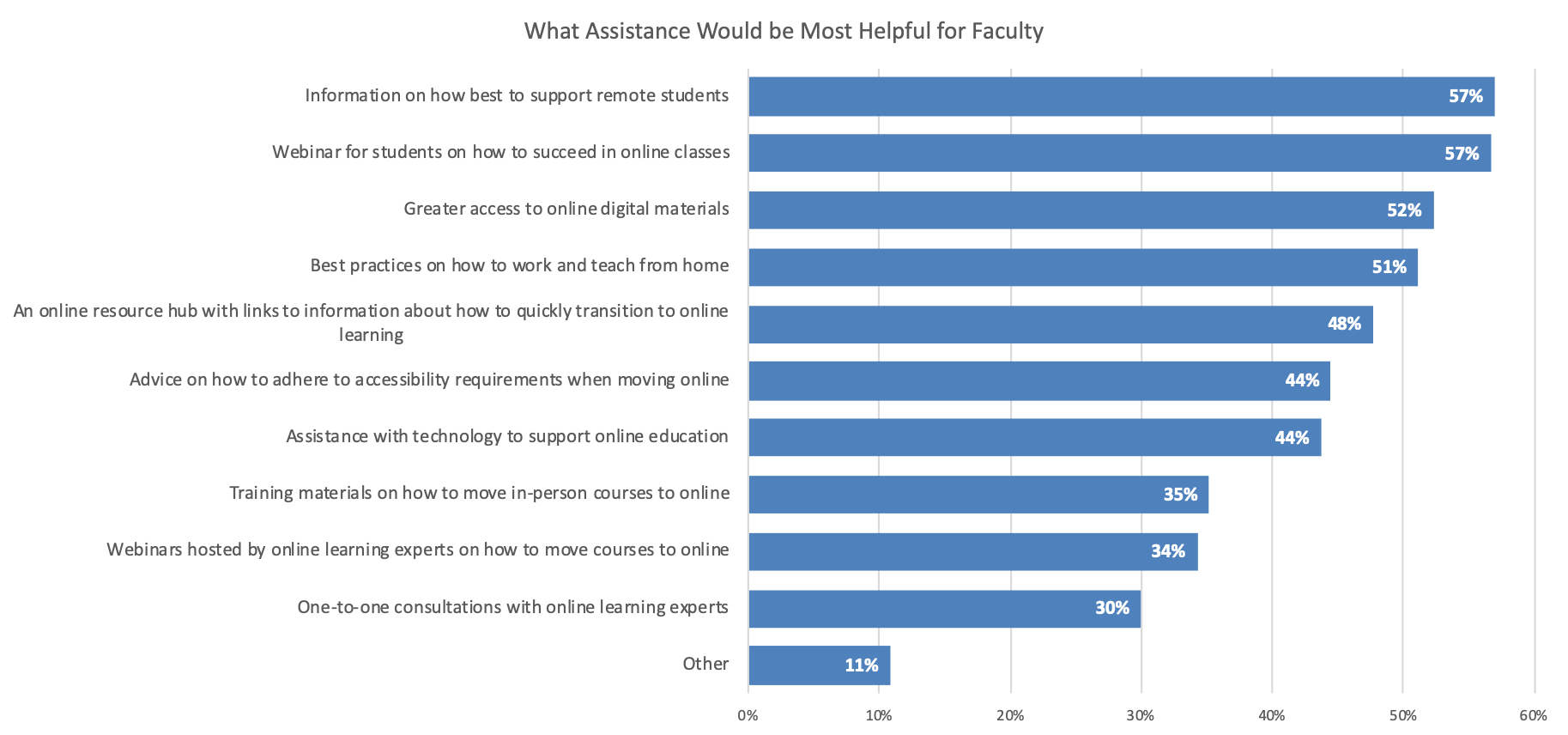

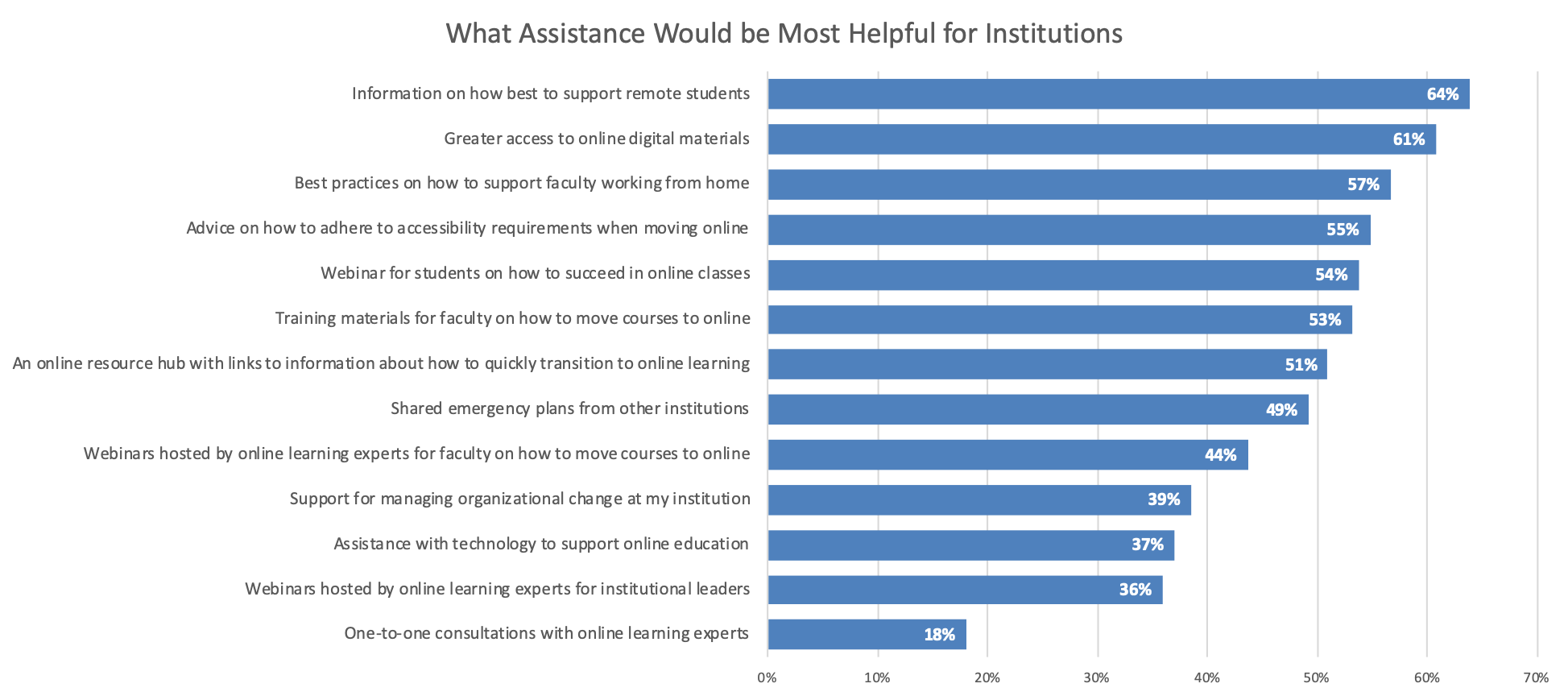

A last set of questions in the survey asked instructors and administrators alike what assistance they could use in better ensuring that they can deliver a quality educational experience to their students.

Both groups focused on support for students. Professors' top choices were information on how best to support remote students and a webcast for students on how to succeed in online classes. Slim majorities also asked for greater access to online digital materials and best practices on how to work and teach from home.

Almost two-thirds of administrators said their institutions would benefit from information on successfully supporting remote students, and a majority said they'd benefit from a series of other tools and services to support students and instructors alike.

Taken together, said Seaman of Bay View, the results and open-ended comments respondents made about their experiences and their worries about the fall show the "level of anxiety and scrambling" many instructors felt during this pivot to remote learning.

"It's pervasive the sense of 'I don’t know what I’m doing' or "'I don't know if my students are succeeding online,'" Seaman said.

But it's also clear that despite that anxiety, institutions and instructors made significant changes on the fly in their teaching practices and expectations to try to pull off a required, if undesirable, transition this spring.

The big question going forward is what professors and colleges can do in the coming weeks to ensure that if campuses are still closed, wholly or partially, to students in the fall, they can meet what is likely to be a much higher set of expectations for quality instruction and learning.

Some of them are clearly concerned.

"Many of my students don't have consistent access to the technology needed to make the online classes possible," said one professor at a four-year public university. "I worry we will lose our most vulnerable students if we continue to be online in the fall. I am also worried about managing my own time if I need to keep working from home, homeschooling and dealing with all the additional demands of my students and family in this crisis."