You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Strange to think it, but the word “gentrification” started out as a piece of social science jargon. The British sociologist Ruth Glass coined it in a book from 1964 to name a process underway in parts of London, where whole working-class neighborhoods were morphing into zones of a conspicuous poshness. The process, once underway, moved rapidly “until,” she wrote, “all or most of the original working-class occupiers [were] displaced, and the whole social character of the district is changed.”

She refrained from speculating on whether the trend might emerge elsewhere. It did.

Soon architects and urban planners in the United States were also discussing gentrification, frequently putting the term in quotation marks and flagging it as an imported neologism. So it was treated by The New York Times upon its first appearance in 1974 and for the first few years afterward. By early 1979, a Times columnist risked casual mention of “a Harvard Business School graduate putting his money in gentrification instead of pork bellies,” with reasonable confidence that readers would know the word; in the 1980s, it was in frequent use throughout the paper. Perhaps the clearest sign of its full incorporation into the vernacular came when an entry defining gentrification was posted to the Urban Dictionary, a crowdsourced reference mainly covering slang and idioms, with special attention to innovations in profanity.

Gentrification, we read there, “often begins with influxes of local artists looking for a cheap place to live, giving the neighborhood a bohemian flair,” which then “attracts yuppies who want to live in such an atmosphere, driving out the lower income artists and lower income residents, often ethnic/racial minorities, changing the social character of the neighborhood.” This is not at all bad as a definition, but it is also interesting for how it suggests something important about gentrification today—namely, that gentrification is a phenomenon people notice. Once a sociological abstraction, it has been assimilated into city dwellers’ ordinary awareness of the urban landscape.

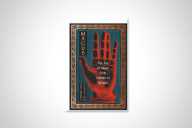

Familiarity can breed resignation. In her groundbreaking essay, Ruth Glass called gentrification “an inevitable development, in view of the demographic, economic, and political pressures” within London. While giving all due respect to her predecessor’s work, Leslie Kern, an associate professor of geography and environment and director of women’s and gender studies at Mount Allison University in New Brunswick, Canada, takes Glass’s fatalism as a self-fulfilling prophecy that must be dismantled in the interest of vulnerable populations. Kern’s Gentrification Is Inevitable and Other Lies (Verso) challenges a number of well-entrenched perspectives on gentrification from the anticapitalist left as well as the market-minded right.

Calling them “lies” in her title is unfortunate, albeit attention-grabbing. (Stridency sells.) In a series of well-argued critiques, the book takes on received ideas and rationalizations about the dynamics and consequences of gentrification. One is the notion—evident in the Urban Dictionary entry—that artists and hipsters gentrify a neighborhood by changing its character. Another is that gentrification works to the benefit of women and LGBT+ communities. Such judgments may be mistaken, but seldom are they meant to deceive.

The role of artists, bohemians and their hangers-on offers a good starting point for an overview of the author’s larger argument. (The indicated cohorts overlap somewhat with university populations.) Kern draws on Pierre Bourdieu’s theory of cultural capital, quoting his definition of it as the “collection of symbolic elements such as skills, tastes, posture, clothing, mannerisms, material belongings, credentials, etc. that one acquires through being part of a particular social class.” She acknowledges that groups with far more cultural capital than income tend to gather where the rents are cheap. And their concentration in a neighborhood can have a magnetic effect. Early discussions of gentrification treated it as a form of middle-class rebellion against life in the suburbs.

The result, over time, is what Kern calls the “paradox of priming for your own displacement,” through which “groups that typically have little more than cultural capital are priced out by successive waves of gentrifiers with relatively more capital of all kinds.” All this may appear to be the unfolding of an organic process—and perhaps it did once proceed without anyone having the conscious intention to change an area’s demographics. But in more recent decades, gentrification has taken shape as a conscious strategy “wielded by those who actually have enormous capacity to remake cities and neighborhoods, like developers and city policymakers.”

Not that the hipsters play no role, then, but their impact is infinitesimal compared to any given zoning commission. Yet taking gentrification as just another manifestation of neoliberal capitalism—a form of social engineering carried out under impersonal financial imperatives—can also make the changes look inevitable, hence irresistible. While making use of more or less Marxist analysis, Kern takes her distance from any narrowly conceived understanding of gentrification as an economic phenomenon.

Early interpretations of gentrification treated “women’s increased participation in the paid workforce, their higher educational attainment, and the growth of dual-income families” as driving forces. But Kern’s feminist analysis of the actual gender dynamics is far from emancipatory. Increasing real estate values make it profitable to evict poorly paid tenants, with an impact on single mothers and women of color that is particularly destructive, in part because they “rely heavily on the informal, place-based networks that they develop in order to help with child-care [and] transportation.” Likewise, seniors and people with disabilities are vulnerable to what Kern calls “the slow violence of neighborhood transformation”—not just from the threat of eviction but because of their reliance on health and social services in their neighborhoods.

Kern’s book is thorough in its intersectionality, making both connections and distinctions between gentrification and the dispossession of Indigenous peoples, and she marks the differences in impact on lesbians, trans people and gay men. The penultimate chapter surveys a number of efforts—mostly in Canadian and U.S. cities—to stop gentrification or mitigate its effects, “ranging from symbolic, to direct action, to policy interventions, to actively building new housing alternatives.” That may be the logical place in the book to discuss such campaigns, but I have to wish there had been some foreshadowing of the grounds for hope. With the brunt falling heaviest on people with little access to resources, resistance may not be futile, but it seems like a very long shot. Kern complains that academics tend to treat what activists have learned as anecdotal, when not writing about gentrification in the tones of a coroner’s report. Her book is sobering at times, but at least lively.