You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

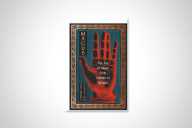

The objects Wendy A. Woloson holds up for inspection in her book on “the history of cheap stuff in America” could be sorted into a number of bins: knickknacks, tchotchkes, keepsakes, souvenirs, cheapjack, premiums, prizes, gimmicks, gadgets and probably a few more. A Venn diagram would show much overlap. But taken in aggregate, the most general category is the one the author, an associate professor of history at Rutgers University, uses as her title: Crap (University of Chicago Press).

The expression “bric-a-brac” might also be suitable, though it lacks quite the punch. Calling something crap is a value judgment, of course; it is on the continuum that shades into fighting words. But arguably it is a more nuanced judgment than that of rude dismissal. Crap includes shoddy merchandise and bad bargains, kitsch ornaments and novelty gags, free promotional trinkets and overpriced “gifts for the person who has everything” destined for the yard sales of ungrateful recipients.

These things are crappy in different ways, and Woloson acknowledges that the perceived crappiness of a given artifact can be a matter of degree as well as an expression of personal taste. But at the same time, it is a historical phenomenon: the product of mass production, low-margin merchandising and, in the author’s phrase, “invention for invention’s sake.”

Here it proves instructive to consider the example of plastic vomit.

A “novel and material iteration of carnivalesque traditions dating back to the Middle Ages, if not earlier,” Woloson notes, plastic vomit was also a triumph of industrial ingenuity that only reached the marketplace in 1959. This was “not, presumably, because it suffered from a lack of market demand but because materials technologies had not yet caught up to consumers’ incipient needs.” Its manufacture required “latex and sponge to be married together to produce just the right kind of texture that blopped out into just the right kind of shape.” (To judge by a photograph, the challenge of producing a credible replica of feces that could be hidden in a box of matches was met decades earlier.)

Marketed under the brand name Whoops, synthetic barf quickly sold hundreds of thousands of units per year. “Postwar American consumers,” Woloson writes, “surrounded as they were with their new-fangled appliances and automobiles, all sleek lines and chrome, may have found something liberating in pedestrian and vulgar commodities that evoked more distant and ribald pasts.”

Her point about the faint echoes of medieval retching from the pages of Rabelais is well taken, but adults of the Eisenhower and Kennedy years were probably not the main market. Fake vomit was akin to Mad magazine without the wit. Just picture Ward Cleaver -- faced with an all-too-realistic mess of tossed cookies on the dining room table -- losing his temper with Beaver and yelling, “You spend your allowance on this crap?”

But the story of plastic vomit is also one of sad decline. “For decades a reliable staple of the novelty market,” we read at the end of the book, “it is now too crappy to be any good.” Customer reviews posted online express dismay at the shoddiness of today’s fake vomit: “‘Very disappointing. It does not look at all like throw up.’ … ‘Would only fool a blind person.’ ‘Not as natural as one would hope.’” The high-quality fake vomit once made in the U.S.A. has given way to cheap knockoffs manufactured overseas.

Assessing a commodity as a piece of crap is a normal part of consumer experience: one that everyone, sooner or later, must apply to some purchase of their own. Some items manage to conceal their crappiness long enough to inspire buyer’s remorse. Others are more blatant. Woloson quotes a 19th-century commentator on the then-new phenomenon of the 10-cent store who described the goods on offer as being “of infinite variety but generally of a cheap sort … a little of everything and nothing of value.” A newspaper editor warned readers “not to complain if they attempt to get something at half of what it is worth, and then find it was not worth half of what it was claimed to be.” To gripe would be “adding stupidity to dishonesty.”

Alongside her account of how countless nonessential and often barely usable commodities made their way to America’s markets, attics and landfills, Woloson considers the mixed and contradictory emotional response to all this dubious abundance. Crap is the result of our remarkably persistent eagerness to acquire, on impulse, stuff that seems desirable for reasons that usually do not pan out -- often not even in the short term. Most crap is so ephemeral that even the concept of planned obsolescence barely applies. (The pleasure to be had from a Cracker Jack prize is more or less exhausted by fishing it out.) But the moment of disillusionment seldom sticks.

A cynical or perverse variety of consumer sensibility has taken shape. “Often,” Woloson writes, “we are not at all deceived. We buy cheap stuff knowing full well how crappy it is.” In late 20th-century American society, it was commonly understood that anything promoted via infomercial -- especially one bearing the suffix “-omatic” -- was almost guaranteed to be crap. Yet such products somehow made a profit. No statistics are collected on it, but I suspect that a disproportionately large share of advertising on social media is associated with what the author refers to as the Crap-Industrial Complex. “It takes creativity,” she writes, “to generate new kinds of crap in this age of total surplus.” A better use of ingenuity would be to find ways to decompose the existing synthetic excretions back into the raw materials they've wasted.