You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

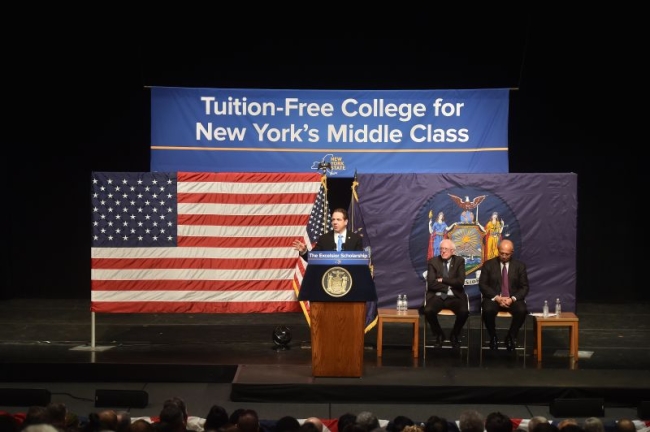

New York Governor Andrew Cuomo announces the Excelsior Scholarship.

New York Governor's Office

Every day for the past few weeks, my colleagues and I have received emails from students at the large community college where we work, asking how they can receive their free tuition. The phone is ringing off the hook with similar questions. One email reads, “I was told by a colleague, and well, the world, that starting in the fall tuition is free for New York residents. How can I take advantage?” Another person on the phone asks, “When does my free tuition start? I can’t afford next semester, but now it’s going to be free. I even saw it on the news.”

In fact, it’s been all over the media: New York is the first state in the nation to offer free two-year and four-year public college to its residents. Last month, Governor Andrew Cuomo signed the Excelsior Scholarship bill making all public colleges and universities tuition-free for families with under $125,000 (by 2019) in annual household income. The bill goes into effect this fall and, according to (exaggerated) estimates by the governor’s office, will impact nearly 940,000 families. It has been “hailed as a breakthrough and a model for other states that will change the lives of students at public colleges.”

The plan to make all public colleges and universities in New York free sounds great, at least in theory. After all, much like health care, free higher education should be a basic human right, not simply a luxury for those that can afford it. And, for the most part, the Excelsior Scholarship is a first step toward making higher education more accessible for middle-class New Yorkers.

But rather than helping New York’s most needy and deserving families, a major imperative behind the bill is political. Cuomo gained a great deal of political capital by New York becoming the first state to declare college free. And as someone who has worked in both the State University of New York and City University of New York systems for nearly a decade, I can tell you from experience that the Excelsior Scholarship program is not going to significantly increase college accessibility in New York City. In fact, it may actually hinder the accessibility of higher education and the availability of resources for the state’s most vulnerable and underserved student population: the low-income, first-generation students of color who make up the bulk of CUNY’s student population.

Here are some key ways this piece of legislation could actually have a negative impact on students, faculty and staff members.

The Excelsior Scholarship is not free college. The Excelsior Scholarship program is set up as a last-dollar plan, which means it will bridge the gaps for eligible students between their financial aid package and the institution’s tuition, covering no more than the full cost of tuition for eligible students. At the community college level, students are only eligible for a total of $5,500 under the program.

Meanwhile, most CUNY students already do not pay tuition. In fact, 66 percent attend tuition-free, covered by Pell Grants and Tuition Assistance Program grants, while nearly half come from families with household incomes of less than $30,000, making them eligible to receive “full” financial aid.

Given the fact that most students already do not pay tuition, it is not the cost of tuition that makes attending college difficult for low-income urban students but rather the unofficial costs of college: transportation, books, cost of living and lost wages from the inability to work. Those expenses lead to a one-year retention rate of 61.9 percent (fall 2015). Without alleviating or assisting with any of these peripheral costs, this Excelsior Scholarship will do little or nothing to make college more accessible for low-income students.

At CUNY and SUNY community colleges that largely serve a low-income population that receives a great deal of support through existing financial aid, the program will only help a small fraction of the student population. In fact, at a college like mine, administrators expect it to benefit only about 300 to 500 students.

Finally, the application window for Excelsior is June 1 to July 15, giving students a very small time frame to apply for the aid -- a window that many of the distracted, incredibly busy, time-strapped and underprepared urban students will surely miss.

The credit accumulation requirement will be devastating to the neediest students. The Excelsior Scholarship requires that all students accumulate 30 credits in each academic year in order to maintain the scholarship. On paper that sounds simple enough. Obtaining 30 credits a year, times four years, means on-time graduation.

But nationally, only about 60 percent of college students graduate with B.A. degrees in six years, finishing at a rate far slower than the 30-credits-a-year requirement would require. At CUNY, the five-year graduation rate is much lower, hovering around 30 to 33 percent in past years.

Indeed, for low-income and academically underserved students, this rate of credit accumulation is difficult, if not impossible, to achieve -- primarily for two reasons. The first is that most CUNY students, because of their absolute financial need to work -- to cover the costs I’ve described like books, housing and transportation -- are simply unable to take 15 credits in a given semester. That makes it incredibly difficult to reach the 30-credit requirement without taking a bulk of summer and winter classes. And, as those working at CUNY know far too well, students cannot put college over financial stability because of the need to help support their households and the high cost of living in New York.

The second reason is that, because of being underserved in failing New York high schools, many CUNY students enter college requiring multiple remedial or precollege-level courses. Such courses are required to get students up to basic college proficiency but do not allow them to earn any credits. The vast majority of students, especially at the community college level, require at least one remedial course -- and some require three or more courses -- making it impossible for them to accumulate the 30 credits in their first year needed to qualify for the program.

Further, under the program, colleges will be asked to waive students’ remaining tuition (after Pell Grants, TAP grants and other aid is taken off the top) for those who qualify. Once a student meets the requirements, the state will reimburse the college. That puts financially strapped colleges and universities in a position of economic risk and can further reduce the quality of higher education in the state of New York.

But that provision of the bill has the most devastating impact on academically struggling students. Students who receive the Excelsior Scholarship will have their tuition waived but will be forced to reimburse the institution for it if they do not meet the program’s requirements. That means that students who fail a course -- and because they come into college so woefully underprepared that can be as many as 70 percent of all students -- and therefore do not reach the total of 30 credits will be required to pay a portion of their tuition back.

That will cause an even greater financial burden on the most at-risk students, as they will not have planned for such expenses. (After all, isn’t college free now?) And while students who have faced personal hardship will be able to reapply for Excelsior, it is yet to be determined exactly how that will happen and what stipulations will be put in place for a student to regain the scholarship.

Colleges will have more incentive to recruit international students. International and out-of-state students pay more tuition than in-state residents. With in-state students eligible for Excelsior, the bill will only further encourage public colleges and universities, seeking greater revenues, to put international and out-of-state students at the center of their recruiting goals. That has the potential of further steering the student population away from the low-income, first-generation college students that CUNY has traditionally served.

Tuition increases will make college less accessible for those who don’t qualify for Excelsior. The bill includes a provision that allows CUNY and SUNY to increase tuition each year for those students who will be paying tuition. For example, if a working-class student does not receive full financial aid to cover tuition and is ineligible for the Excelsior Scholarship because of an inability to meet the credit-accumulation requirements, they actually could face a public university system that is even more expensive than it was before the program. By adding a tuition spike into the bill, legislators and the governor actually made college significantly less accessible for the students who do not qualify for the program, defeating its very purpose.

Calling college “free” could take a psychological toll. While many students already attend CUNY for little or no tuition, they are aware that their education is paid for through a complex combination of financial aid and personal costs. Labeling tuition as free could have a profound impact on students’ desire to take college seriously and reduce the burden on them to perform academically once admitted. This is not to say that we shouldn’t strive toward making public education accessible to all students and that removing tuition expenses isn’t a crucial and necessary step. But calling college “free” without critically examining how our underfunded K-12 system prepares students to face the rigors of undergraduate life could have unintended consequences.

Elevated admissions requirements will hurt low-income, first-generation students. The headlines have gained much attention that students both within New York and those outside it (once residency is established) will be vying for a spot in one of our so-called free colleges. And given the finite number of seats at the SUNY and CUNY colleges, I fear the competition will result in elevated admissions requirements for public colleges.

The elevated admissions requirements will push more low-income, urban, first-generation students toward community colleges because they will not be admitted to four-year colleges. Community colleges, while doing great work in many respects, do not afford students the same opportunities, type of education and level of services that four-year colleges can offer.

Also, while enrollment at CUNY and SUNY spikes, many students will opt out of attending private colleges. Of course, the exception will be the upper class or super rich, who will still choose private colleges for the prestige -- creating a two-tiered system where the rich go to private colleges and the working-class masses attend underfunded public institutions. That will only further our national wealth-inequality gap.

The bill is not aimed at low-income, first-generation working families. This law does very little to help families who earn under $30,000 a year who are receiving existing financial support to pay for college, yet are still struggling to pay for all affiliated costs. As CUNY activist and New Yorker Christopher Espinoza astutely wrote, “I feel insulted that CUNY and SUNY will now exclusively cater to middle-class families with sufficient incomes, in my opinion, to pay a $6,000 yearly tuition. I agree that there are lots of families with above-$80,000 combined incomes that have trouble paying for college for their children. But this is terrible policy in the sense that it is a gross overreach on our governor’s part to push for a middle class that is not struggling in a time when the divide between the working class and the middle class is wide as ever.”

Enough said.

The bill places greater burdens on faculty and staff members. The legislation contained no plans to increase the pay or number of CUNY and SUNY instructors and administrators -- who are already overworked and underpaid. Faculty members are already teaching more and more courses, with little time left for research and publishing. Increasing the number of students without providing significantly more funding to CUNY and SUNY will result in faculty members teaching even more courses and having more of those courses taught by dedicated but underpaid adjuncts and graduate students.

Meanwhile, support offices like those for financial aid, registration, advising and counseling consistently have long lines that stretch down university hallways while the underpaid and overworked staff members inside struggle to keep up with student needs. That has taken an emotional and physical toll on such support staff, especially those who work with low-income urban students all day without much reprieve. With an influx of new students, the demands will only multiply. Simply offering a “free tuition” scholarship that does not address any of these teaching and staffing concerns will be detrimental to low-income students who require the most attention from CUNY and SUNY’s highly professional, committed staff.

Final Thoughts

The goal of this piece is not to discredit the Excelsior Scholarship but rather to spark conversation about how we can design better legislation. The bill could have done many things to help higher education in New York more effectively. For instance, it could have directed more money to New York’s Tuition Assistance Program, which is designed to help the state’s poorest students -- those likely to be first generation or students of color. It could have appropriated more for college-readiness programs, which would reduce the need for remedial courses. It could have contained provisions to decrease the cost of room and board while increasing mental-health and career counseling on campuses -- services that students desperately need but have limited access to. It could have also included provisions to increase the number and raise the pay of faculty members, as well as to give more financial aid to low-income, part-time and other needy students.

The Excelsior Scholarship seems to have been designed with traditional students in mind -- those who attend full-time, come from high schools that fully prepared them for the academic rigors of higher education, have financial support for housing and other needed services, and can graduate on time. It seems to have been designed for the ideal student. But, as anyone who works in higher education in New York knows, an institution like CUNY serves few “ideal” students. Rather, the students at CUNY and SUNY are struggling to keep up with their course work while working multiple jobs to cover the cost of housing, transportation and books. They need a college assistance program that will make substantial changes to the lived realities of their lives.

Such a program is within reach. Speaking specifically of the CUNY system, the projected city of New York budget surplus was $963 million in 2016 (with an overall budget of $78 billion). A truly free program for CUNY -- one without the stipulation of the Excelsior Scholarship, like credit-accumulation minimums -- would cost an estimated $812 million. Beyond that, New York City could also easily reduce the cost of transportation by giving students free or discounted Metrocards and the cost of textbooks by offering access to ereaders or online texts. As a city and a state, we have the resources and ability to offer a truly free higher education to our citizens.

While the Excelsior Scholarship bill has been marketed as a magic pill, it is in fact a supremely flawed piece of legislation that reflects little concern for the harsh economic realities that the most at-risk students are facing. These students, along with our universities’ faculty and staff members, deserve better.