You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Penguin Random House

Ours Was the Shining Future: The Story of the American Dream by David Leonhardt

Published in October 2023

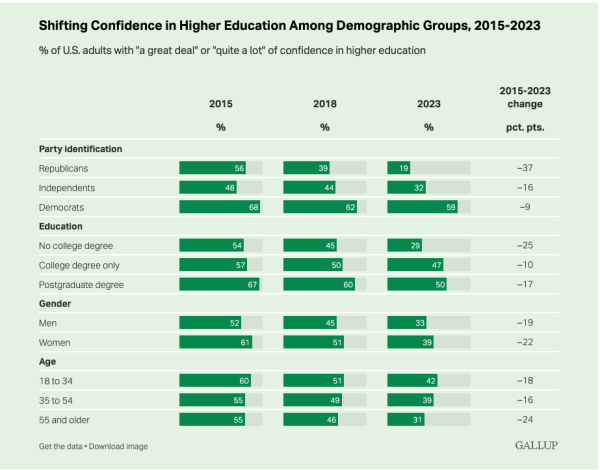

In July of this year, Gallup reported extraordinary polling results on the decline of American confidence in higher education. From 2015 to 2023, the percentage of Americans who reported a “great deal” of confidence in higher education declined from 28 to 17 percent. During these same years, the percentage of respondents who said they have “very little” trust in the institution of higher education grew from 9 percent to 22 percent.

The results were even more striking when the survey was analyzed by demographics, party identification and education. In 2023, fewer than one in five Republicans and fewer than three in 10 non–college graduates reported a “great deal” or “quite a lot” of confidence in higher education. While no demographic or political group reported greater levels of confidence in higher education between 2015 and 2023, the declines among those without a college degree and Republicans were comparatively large.

I begin this post on Ours Was the Shining Future with these Gallup results because I think David Leonhardt’s book and these data should be considered together. Leonhardt, a celebrated journalist at The New York Times, has written a book that (among other things) attempts to explain why so many working-class Americans have abandoned the Democratic Party. The arguments he brings to explain Donald Trump’s appeal to a large proportion of the non–college educated might equally be applied to understanding the Gallup results on declining confidence in higher education.

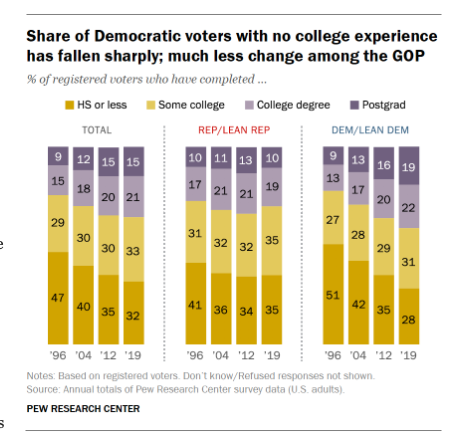

Why have Democrats lost so much support among voters with some college or only a high school diploma? For Leonhardt, the reason for this shift rests primarily with the Democrats failing to place the interests of the working class at the center of their political rhetoric and policy priorities.

Borrowing from Piketty, Leonhardt explores how an emerging Democratic “Brahmin left” supported policies such as free trade and immigration reform while failing to emphasize bolstering unions and protecting manufacturing jobs.

Ours Was the Shining Future traces the twin histories of rising inequality and deepening political polarization. Before reading the book, I had not realized that Bobby Kennedy, assassinated in 1968 while running for president, was building a moderate working-class coalition. Kennedy was willing to combine a tough-on-crime message with one of economic justice, a rhetorical territory Leonhardt thinks subsequent Democrats largely abandoned.

Setting aside how Democrats might regain working-class votes, how might higher education reverse its declining levels of confidence among Republicans and adults without a college degree?

One way that higher education's social license may be deepened across all Americans would be if universities invested as much effort in celebrating the people who make our campuses run as they do in promoting their presidents, provosts, deans and professors.

How often are our campus colleagues who clean our buildings, maintain our facilities, protect our communities and feed our students highlighted on university websites, promotional materials or campus tours?

The reality is that universities are often among the best employers for non-college-educated workers in the cities, towns and regions in which they are located. How often does a university president publicly state that the institution’s goal is to provide the highest wages, the most generous benefits and the greatest job security possible for every person employed by the institution?

In higher education, the outcomes we focus on—and the university missions we adopt—almost always center around student success, learning and knowledge creation. What if one of the core functions of the university was understood as creating and protecting secure middle-class jobs?

Can’t we have both student success and good jobs for everyone a school employs? Doesn’t student success (and learning and research productivity) depend as much on all the workers that a university employs as the quality of the faculty? After all, there will be no learning or knowledge creation if our facilities are not maintained and students have no place to eat.

Ours Was the Shining Future should challenge the leaders of the Democratic Party to rethink strategies to broaden its appeal to all voters. At the same time, I hope the book causes us in higher ed to think about how we might learn to support and publicly celebrate every person who works at our universities.

What are you reading?