You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Harvard’s introductory computer science course is embracing AI to help students.

iStock/Getty Images Plus

The rapid march of AI into classrooms has reached Harvard University’s flagship computer science course, which is now using ChatGPT as a way of freeing up teaching assistants to spend more quality time with students.

It is one of the latest applications for artificial intelligence, a technology that’s caused both excitement and alarm among educators since OpenAI’s ChatGPT was released in late 2022. The ripples from AI’s impact have touched everything from admissions to how teachers craft assignments.

Harvard’s Computer Science 50: Introduction to Computer Science rolled out AI as a tool in its summer program about two weeks ago. The popular course has about 70 students this summer and will have more than 600 in the fall.

“We’re very much steering into AI and what we view as the potential upsides,” said David Malan, the Gordon McKay Professor of the Practice of Computer Science. He said there is a real need for more guidance for students in computer science classes.

David Malan

“Even with the generous resources we have now, it’s just not enough,” Malan said. He said the hope is to “support students as we can through software and reallocate the most useful resources—the humans—to help students who need it most. It’s not to reduce the number of teachers, but to enhance them.”

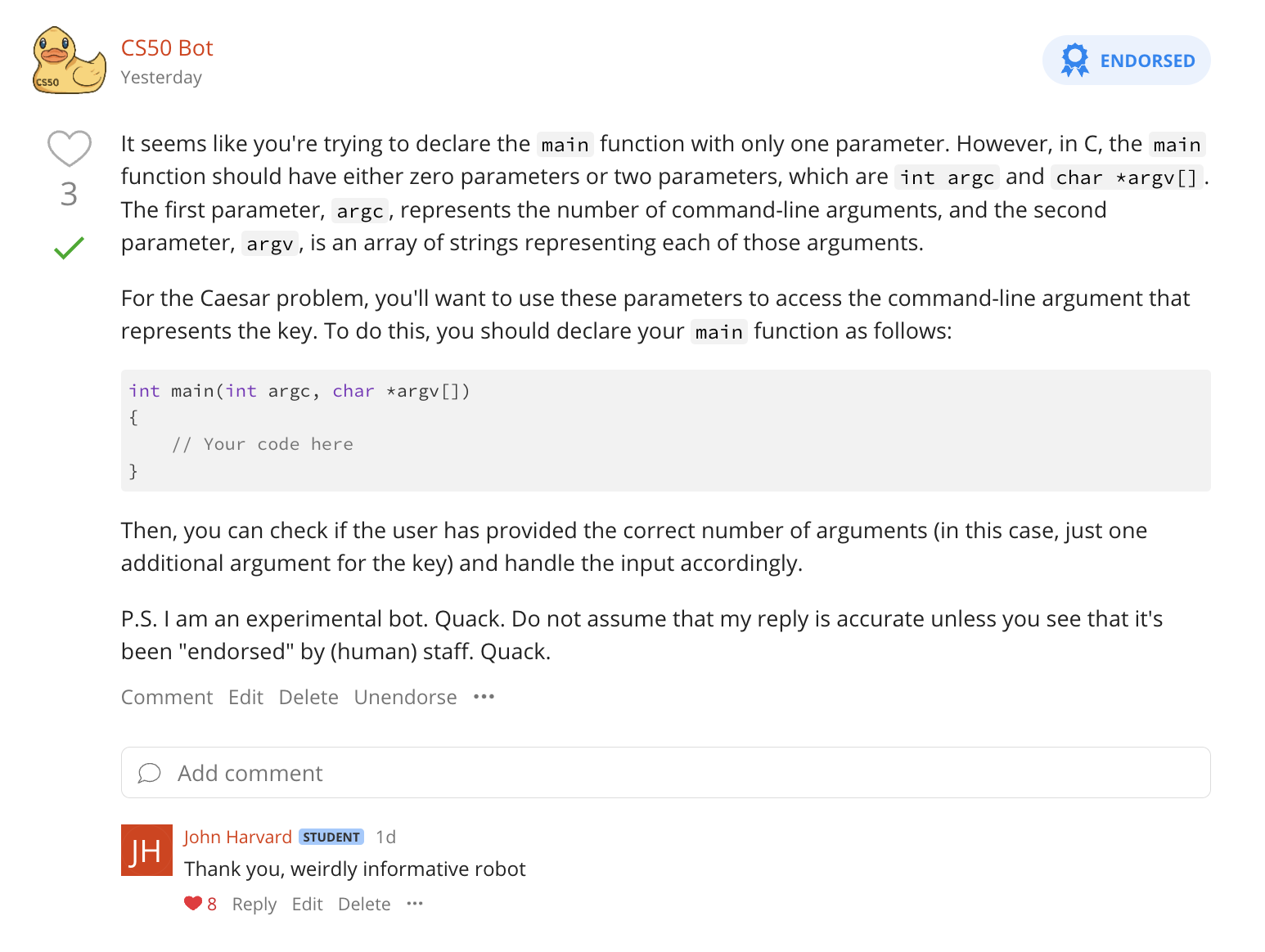

Building upon ChatGPT, Harvard is using the technology to help computer science students understand highlighted lines of code and advise them on why and how to improve their code’s style. It is also used to answer frequently asked questions.

Malan said the technology is not intended to replace TAs and professors but to help them make better use of their time.

Lynne Parker, director of the AI Tennessee Initiative, believes using AI this way could be a positive change as many institutions face a TA shortage, particularly in computer science.

“I don’t have any fear it’ll take away existing jobs,” said Parker, who also serves as an associate vice chancellor at the University of Tennessee at Knoxville.

“It will help scale these kinds of assistants to more students,” she said. “And the goal of every student having easy access to personalized help in courses is a fantastic goal.”

Harvard is the latest in a growing list of institutions adopting AI. Admissions offices, including Georgia Tech, are “experimenting” with the technology. Other institutions have launched AI faculty workshops. And some institutions, including Purdue University, Emory University and the University at Albany, have hired dozens of faculty focused solely on artificial intelligence.

At Harvard, the current use in introductory computer science is only the beginning, Malan said. He also described four additional applications he hopes to roll out soon: AI explaining error messages, helping students find bugs in their code, assessing the design of programs and assessing students’ understanding through AI conversations.

These future features emphasize nudging students in the right direction by asking rhetorical questions, much like a TA would, versus outright telling students the problems with their code.

The Harvard class could serve as a standard for a more widespread adoption of AI, especially among the more tech-savvy computer crowd, according to Parker.

The goal of every student having easy access to personalized help in courses is a fantastic goal.”

—Lynne Parker

However, it might take a bit more convincing for some faculty, said Fiona Hollands, founder of the research and evaluation organization EdResearcher.

“There’s faculty saying, ‘We’ve been doing it this way for 20 years—why change?’” said Hollands, a former research consultant at the Center for Technology and School Change at Teachers College of Columbia University.

Hollands pointed to the difficulty getting faculty to do anything online before the COVID-19 pandemic created a “forced situation.” She said, “Institutions of higher education don’t tend to look toward, ‘Oh, how can we make it more efficient?’”

Malan pointed to the potential of AI to evaluate student’s code design, which is largely subjective and time-consuming for TAs. He said that while TAs spend hours grading the design, students, on average, scan a TA’s comments in less than 14 seconds.

It’s never been a good use of time for TAs and students, Malan said. “We don’t want to remove humans from the process entirely, but it’s amplifying the impact they have on student experience.”

Beyond freeing up TAs, the easy access to AI is intended to help students more quickly troubleshoot instead of becoming increasingly frustrated while waiting for a TA to become available.

“It’s possible to use this to get unstuck, which is what they do with human assistants, but often they’re not available,” Parker said. “So, often students will get stuck, say, ‘I’m giving up’ and quit. [This technology] could help with retention.”

Malan emphasized that AI is not a be-all and end-all and is evolving, and he said students are reminded of this when the AI answers their questions. A literal footnote attached to each answer cautions students to not take the answer at face value unless a TA has approved it.

While this AI application is currently only being used by the computer science course, Malan hopes to roll it out to another course this fall—and put it outside the typical STEM walls.

“My hope is to collaborate outside of computer science and STEM, particularly looking in humanities as another proof of concept,” Malan said. He said he’d like to show “it’s not the domain of STEM alone; it’s a positive impact across the board.”