Free Download

Many campus chief financial officers lack confidence in the sustainability of their colleges' business model over the next decade -- but they also seem loath to take cost-saving measures that could ignite campus controversy, according to a new survey by Inside Higher Ed and Gallup.

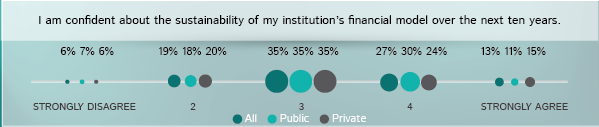

The survey, which will be released in conjunction with the upcoming annual meeting of the National Association of College and University Business Officers, is based on the responses of chief financial officers at 438 colleges and universities. It finds that just under a quarter of business officers (24 percent) strongly agree they are confident in the sustainability of their business model for the next five years, and only 13 percent strongly agree they are confident in their model over the next 10 years. A copy of the survey report can be downloaded here.

Two-thirds of CFOs believe news media reports suggesting that higher education is in the midst of a financial crisis.

Yet when it comes to specific ways to balance their budgets, CFOs are wary of several ideas that could agitate key campus groups. Do they have any plans to have senior faculty teach more undergraduates, revise tenure policies, promote early retirement for administrators and staff, outsource more academic programs or cut funding for intercollegiate athletics? A quarter or fewer of the CFOs said they planned to try each of those tactics.

About the Survey

Inside Higher Ed's 2014 Survey of College and University Business Officers was conducted in conjunction with researchers from Gallup. Inside Higher Ed regularly surveys key higher ed professionals on a range of topics.

On August 6, Inside Higher Ed editors will lead a free webinar to discuss the results of the survey. To register for the webinar, please click here.

The Inside Higher Ed survey of CFOs was made possible in part by advertising from Higher One, Inceptia, Jenzabar, Workday and Xerox.

Other techniques got more support: reducing administrative positions (37 percent agreed they would do this in the coming year), eliminating underperforming academic programs (37 percent), have part-time faculty teach more undergraduates (35 percent), giving full-time faculty more classes (30 percent), promoting early retirement for faculty (28 percent), outsourcing administrative services (30 percent), and shifting to a web-based model (35 percent).

A majority looked to collaboration to control costs. Over half (55 percent) said they wanted to work with other institutions to provide academic programs. A smaller number (37 percent) wanted to collaborate on administrative services with other colleges.

The numbers were roughly in line with what CFOs said last year and show continued interest in partnerships as a means to reduce costs.

“I think it seems like collaborative work’s time has come,” said Amanda Adolph Fore, a member of the board at the Association for Collaborative Leadership and a higher ed consultant at Next Peak Strategies. “And it’s time to stay clear on mission and have more impact while looking at your spending. It seems like there is more of an openness, especially in areas where people don’t necessarily view themselves as competitors.”

There are already numerous consortiums -- including the Claremont Colleges in California, the Five Colleges and the Boston Consortium in New England, the Committee on Institutional Cooperation that represents Big 10 universities in the Midwest -- and some new projects, like a group of 10 Pennsylvania liberal arts colleges that is trying to cope with the troubles facing the liberal arts.

Part of the calculus behind CFOs’ interest in collaboration is perhaps another feeling they have: only a third feel they can make “additional and significant spending cuts” without hurting the quality of their institution.

Kent Chabotar, the recently retired president of Guilford College, in North Carolina, who has been teaching seminars this summer to higher ed leaders, said collaboration is not easy.

“The fundamental problem with that is it’s easier to talk about collaboration and harder to do,” he said. “Because if you’re collaborating or sharing services, you’ve got to have the same standards and you’ve got to be willing to admit you’re not, quote, unique, unquote – and I think that’s hard for some people.”

Another strategy to help balance budgets – seeking full-pay students (46 percent of CFOs said they planned to do this in the coming year) – could also be tricky.

“It almost feels like there’s 4,500 Persians chasing 300 Spartans called full-pay students – good luck,” Chabotar said.

Divestment

Despite a few wins for activists that want college endowment funds to stop investing in coal, gas and oil interests, the vast majority of CFOs don’t think their endowments should sell off fossil fuel holdings. Pitzer College in California committed to quickly selling off most of its fossil fuel holdings and Stanford University, also in California, announced it would stop investing directly in coal companies.

Only 6 percent of business officers think institutions should dump fossil fuel investments.

Likewise, the survey – conducted before the escalation of Israel’s confrontation with Hamas in recent weeks – indicates that only 3 percent of CFOs would sell holdings in companies that conduct business with or in Israel despite pressure on some campuses to do so.

While CFOs often do have say over the portfolio, they don’t necessarily have day-to-day control or pick stocks, especially if the endowment is managed by a college-affiliated investment entity or a third party.

Still, a quarter of business officers think investment managers should consider political and social issues surrounding endowment holdings when they make investment decisions.

Who Is a Realist?

Chief financial officers continue to think that most faculty members are not realistic about the financial challenges colleges face.

Only 22 percent of business officers agree or strongly agree that professors are realistic – up slightly, however, from last year, when only 18 percent reported the same. When faculty fight cuts at institutions, they sometimes claim the administration is intentionally making an institution's finances look worse than they are.

CFOs think trustees get it, though -- 67 percent say trustees are realistic about the financial challenges their institutions face.

That’s less than the 75 percent of senior administrators that CFOs agree are realistic about the finances.

Debt

Moody’s Investors Service recently continued its negative outlook for the whole higher ed sector, in part because colleges are “living with increased operations, maintenance, and debt service costs even as a new cycle of capital investment builds” and even as tuition revenue remains stagnant.

But CFOs, by and large, are not worried about their own institutions’ debt.

A quarter of CFOs said they strongly agree that their institutions have historically not used debt enough as a financial strategy, although only 7 percent strongly agreed they should take on significantly more debt right now.

All told, half of college business officers said they have an appropriate debt level, 17 percent they have too much, and 26 percent said debt service payments were having a “significant impact” on their operations.

Shared Services

The "shared services" model of administration -- in which key services such as technology or business processes are offered to departments or other parts of an institution out of a central unit -- has been embraced by some high-profile large universities in the last few years, but not without controversy. In several cases, sprawling universities where individual academic and other departments have built up their own technology, human resources and finance staffs have sowed rebellion when they have tried to move those employees into a central unit to improve productivity. The Universities of Michigan and Texas at Austin, among others, have faced protests over their administrative restructuring, and, in Michigan's case, pulled back on their plans.

To try to gauge the interest in and spread of shared services, Inside Higher Ed asked CFOs a set of questions about the practice. But the answers suggest some confusion among respondents about the concept, perhaps due to a lack of clarity in how the questions were worded and the many things that "shared services" can mean to different people. So it's probably wise to view the answers to these questions with a grain of salt.

When asked whether their institutions were using a "shared services" model of operation, a full 54 percent of CFOs said yes. That was most true for CFOs at public doctoral institutions (75 percent), where the recent push for shared services has been most evident, but 60 percent of community college business officers also said their institutions were using shared services.

Two in five finance officers at private baccalaureate colleges said their institutions used shared services.

All those institutions well might have centralized administrative units for information technology, human resources and other functions, and many others may be collaborating with other colleges on some services or processes, either through statewide university systems or consortiums of private colleges. So their answers to the question are understandable from that standpoint.

But it is unlikely that very many of them are adopting the sort of broad "shared services" frameworks that have generated both dreams of big savings (among business process consultants and some campus leaders) and significant pushback against what some faculty leaders and other constituents on campuses see as the incursion of corporate, bottom-line-oriented thinking in the academy.

One other question posed to CFOs probably accurately captures the latter sentiment. Asked to respond to the statement, "Faculty members at my institution support a 'shared services' model of operations, only 8 percent of CFOs strongly agree and 24 percent agree.

Only 26 percent disagree or strongly agree, however, with the rest not sure.

Government Mandates

Private college CFOs, like their counterparts in the public sector, say they are increasingly feeling the pain of government mandates.

Asked to rate a set of issues based on the degree to which they are paying more attention to them now than they were five years ago, CFOs gave the fifth-highest answer to “federal and state government mandates,” with 72 percent agreeing that regulation was drawing more attention. That was up from 68 percent of CFOs in 2013, but the biggest changes were among sectors.

Last year only 59 percent of private college business officers listed federal and state mandates as a matter of increasing concern (compared to 77 percent of their public college peers).

In 2014, that number rose to 67 percent, driven by a sharp increase (to 73 percent from 59 percent last year) among CFOs at private baccalaureate colleges. (Business officers at public doctoral universities also expressed much more concern about regulation this year, with 84 percent citing it as a matter of growing concern. That figure was 75 percent in 2013.)

Among other findings:

- Forty-five percent of private college CFOs (and 50 percent of those at private baccalaureate colleges) agreed that their tuition discount rate is unsustainable. (The figure was 22 percent at public institutions.)

- Large majorities of business officers said their institutions had experienced increases in health care premiums for employees (81 percent) and students (70 percent).

- Nearly nine in 10 CFOs are focusing more on enrollment management issues than they did five years ago.

- Half of business officers agree they can make informed decisions about what academic programs should be eliminated or enhanced.

Doug Lederman contributed to this article.