Free Download

College and university presidents overwhelmingly describe race relations on their campus as excellent or good, are increasingly upbeat about their institutions' financial situations, give President Obama's higher education record a grade of C, and generally dismiss the push to hire campus leaders with nonacademic backgrounds.

Those are among the key findings of Inside Higher Ed's 2016 Survey of College and University Presidents, produced in conjunction with Gallup and published today. (Download a copy of the report here.)

The sixth annual survey -- which drew answers from 727 college chief executives, a 24 percent response rate -- is being released in conjunction with this weekend's annual meeting of the American Council on Education, in San Francisco. Presidents were granted anonymity to encourage candor, but their answers were coded by institution type, allowing for analysis of differences by sector.

Race to the Top?

In recent years, when Inside Higher Ed has asked college presidents to evaluate race relations on their campuses, overwhelming majorities have answered “excellent” or “good.” The figures have been so positive that some critics have accused the presidents of being in denial on the issue.

So would this year, after a fall semester of widespread and intense protests by minority students on campuses nationwide, be any different?

About the Survey

Inside Higher Ed's 2016 Survey of College and University Presidents was conducted in conjunction with Gallup. A copy of the report can be downloaded here.

Inside Higher Ed regularly surveys key higher ed professionals on a range of topics.

On Thursday, April 7, Inside Higher Ed editors Doug Lederman and Scott Jaschik shared and analyzed the findings and answered readers' questions in a webinar. View the webinar.

The Inside Higher Ed survey of presidents was made possible in part by advertising from ELS, Hobsons, Jenzabar and Keypath Education. box ends here.

Not really. In fact, the proportion of presidents who characterized race relations on their campus as “excellent” went up from 18 to 20 percent in the 2016 survey. The percentage who said “good” grew from 63 to 64 percent. So 84 percent of presidents this year believe race relations on their campus are either excellent or good.

The survey found that presidents did seem to be aware of the frustrations of minority students on other presidents’ campuses.

This year, only 24 percent of the presidents described the state of race relations at colleges nationwide as good, and no one characterized them as excellent. That’s down from 42 percent good and 1 percent excellent a year ago.

Another finding from this year’s survey that may surprise protesters concerns the presidents’ evaluation of how well their institutions are serving minority students -- 28 percent strongly agree and 46 percent agree that their institutions are doing a good job. Only 4 percent disagree and only 1 percent strongly disagree.

How is it possible -- after the protests at the University of Missouri at Columbia and Yale University spread to so many campuses, and so many minority students took to social media to talk about how unwelcome they feel on their own campuses -- that so many presidents think their own institutions are doing well on race relations?

The figures didn’t shock Shaun R. Harper, but he wasn’t happy about them, either.

Harper is founder and executive director of the Center for the Study of Race and Equity in Education at the University of Pennsylvania. He does research on race relations nationwide, working with colleges that want to get a sense of their climate and improve it.

“This is one hell of a finding,” Harper said of the high proportions of presidents who believe race relations are good at their institutions. “It is consistent with what I've seen for many years. Administrators think that a blackface party or a racist incident can happen at other places, but something like that can never happen here.”

Harper recalled something that happens frequently when he and his colleagues are talking to students on campuses and create focus groups of people of different races and ethnicities.

“We’ll ask white students which groups of students are likely to feel like they most belong here, and they get confused and say, ‘Everyone feels like they belong here,’” Harper said. “Meanwhile, in the very next room, someone on our team is talking to black women who are literally crying while talking about how difficult it is to be there.”

Some of those white students, Harper said, “grow up to be college presidents who never really learned to understand the realities of race on their campuses, who never learned the real experiences of students, faculty and staff members of color.”

The statistics, he said, “make me worry even more about how out of touch the college presidents and other senior leaders often are.”

Nathan Hatch, president of Wake Forest University, said he suspected that the presidents rating campus race relations as good were simply asking if they had experienced “huge flare-ups” such as those that attracted so much attention in the fall. Others, he suspected, may be proud of increases on their campuses in the representation of minority students.

Wake Forest hasn’t had major protests in the last year and has attracted an increasingly diverse student body. Hatch said, however, that it’s wrong for presidents to assume that good demographic data and the absence of protests mean that minority students are happy.

With fellow administrators, Hatch has spent a lot of time reaching out to minority students and listening to concerns, and many have such concerns, he said.

“Diversity by itself,” he said, doesn’t create inclusivity. Colleges need to work at that, whether or not they have protests. Personally, Hatch said, he would be “much more cautious” about declaring race relations on campus to be good, even if he feels that his institution is making progress.

A gap between presidents’ views of their own campuses and those elsewhere can also be seen in answers to questions about their expectations about protests in the year ahead.

Asked if they anticipated more protests on racial issues in 2016 in higher education generally, 15 percent said that they strongly agreed that there would be more such protests, and another 51 percent agreed.

But asked to respond to the statement if they anticipate more such protests on their own campus, only 2 percent strongly agreed and 7 percent agreed.

The demands of students protests have ranged widely, and many protests produced long lists of demands. Asked what they thought of the demands, presidents offered both support and skepticism.

Three percent strongly agreed and 19 percent agreed that the demands of student protests were “reasonable.” On the other side, 13 percent strongly disagreed and 25 percent disagreed. A plurality of 40 percent was in the middle.

Some campus protests have made demands touching on issues of free speech. For example, some colleges have been urged to punish as hate speech forms of expression, or to institute new bans on hateful statements made on social media.

More than half of presidents (54 percent) agreed or strongly agreed that some student demands “violated principles of free speech and academic freedom.” Only 23 percent strongly disagreed or disagreed.

Nontraditional Presidents, Pro and Con

For many faculty members and higher education purists, the train wreck that was Simon Newman's brief presidency of Mount St. Mary's University in Maryland was all the evidence they needed that colleges should not hire nonacademics (or at least former management consultants at Bain & Co.) to lead them.

Newman's perceived missteps -- not only his most infamous comment, comparing academically at-risk students to "bunnies" in need of drowning or a "Glock" to the head, but his suggestion that the proudly Roman Catholic university might have too many crucifixes and his decision to fire professors for insufficient loyalty -- displayed a lack of cultural understanding that many traditionalists believe campus leaders who have not come up through the academic ranks have by definition.

"Dreaming: All corporate-style #highered leaders resigned," one professor wrote on Twitter the day Newman stepped down. "It is good news. Still, one down, one zillion to go," another responded.

It turns out that a significant number of college presidents themselves seem to agree with those professors.

More than half of respondents to Inside Higher Ed's survey, 54 percent, agreed or strongly agreed that "the traditional emphasis on hiring presidents with extensive careers in academe is appropriate," while just 22 percent disagreed or strongly disagreed. The numbers favoring the hiring of traditional presidents were highest among leaders of public doctoral universities (76 percent) and public master's/baccalaureate colleges (63 percent), and lowest at private nonprofit four-year colleges (44 percent).

Nearly three in five presidents (58 percent) agreed or strongly agreed that boards should not hire presidents who are strongly opposed by faculty leaders, and nearly half (47 percent) agreed that "college presidents should have a Ph.D." On the latter statement, division between private and public college leaders was significant: 55 percent of public university leaders said a Ph.D. should be required, compared to 39 percent of private college chiefs.

It's not that higher education leaders necessarily think that presidents from outside the academy can't succeed, or that financial acumen doesn't matter when boards choose their leaders.

Twice as many survey respondents agreed as disagreed (50 vs. 25 percent) that "presidents with nontraditional backgrounds have been as successful as other presidents," and nearly two-thirds (62 percent) agreed that the economic challenges facing colleges require a "greater emphasis on selecting presidents with business and managerial skills."

Shelly Weiss Storbeck, co-founder of the search firm Storbeck/Pimentel & Associates, said she was not surprised that a majority of current campus presidents believe that those from traditional backgrounds make the best college leaders -- that describes their own backgrounds, after all.

The latest data from the American Council on Education's American College President study found in 2011 that just 20 percent of college presidents had come to their jobs from outside academe, and more than half had never worked anywhere but in higher education.

"They're probably going to have the view, 'you haven't paid your dues' if you haven't come up" through higher education, Storbeck said.

Storbeck/Pimentel's data on the presidents it has placed in jobs suggest that nontraditional leaders -- which the firm defines as those who've never held a traditional faculty-line appointment -- "seem to be doing as well as the traditional academics," Storbeck said. Some fail, of course, but when they do, "it's on the front page of The New York Times. There's a little hysteria about this."

For every Simon Newman or Bruce Harreld, the businessman whose appointment at the University of Iowa last year generated another round of angst over nontraditional leaders, there's a president who might meet Storbeck's own definition of "nontraditional," such as Clayton Spencer at Bates College or Daniel Porterfield at Franklin & Marshall College, but who thrives, she said. (Both of the latter had significant higher education experience, Porterfield as a vice president for strategic development at Georgetown University and Spencer as vice president for policy at Harvard University.)

Presidents from nontraditional backgrounds often come into their jobs having more to learn about the values and culture of their institutions than their academic peers do, and boards who hire such leaders "had better provide a support system for them that is better than they'd provide for traditionally trained presidents," Storbeck said. "But presidents can come credentialed in lots of different ways."

Stephen J. Nelson, an associate professor of educational leadership at Bridgewater State University who has written four books about the college presidency, said he was surprised -- and somewhat disappointed -- that there wasn't even more opposition from current leaders to the hiring of nontraditional candidates.

While Nelson accepts the premise that nontraditional presidents can succeed -- and that presidents groomed in the academy can have disastrous outcomes, too -- leaders who've come up through the academic ranks, he says, "would seem be more likely to get it when it comes to the core principles of what makes the academy the academy," which he defines as "a commitment to free inquiry, the search for truth, dialogue, debate, etc."

"Of course it's possible that you can have somebody who came up through the academic tradition who, even though it looked like they were buying in, they didn't," Nelson said. "But with the emphasis on hiring outsiders, there's more question whether we have somebody, in an individual institution, or lots of somebodies collectively, who get that and are committed to that, come hell or high water."

Nelson said he was perhaps most disturbed that one in five presidents disagreed with the notion that boards should not hire presidential candidates whom faculty leaders strongly oppose. "You want a prescription for disaster, hire me a president that faculty oppose," he said.

Another search firm leader, Jan Greenwood of Greenwood/Asher & Associates, said that the ultimate question for boards should be less about the background of the candidate than about the goals they have for the president and the traits they believe the successful candidate will need to reach them.

As some boards increasingly start with a bias toward wanting someone from outside the academy to "shake things up," Greenwood said, "the question really should start with what it is that search committees and boards think the person from outside can accomplish that people from inside can't.

"A board may assume that people from outside higher ed will take more calculated risks, or have more financial acumen, or be more strategic. Some may, but many may not. And there's some fabulous talent within higher ed."

Grading Obama

The Obama administration late last year abandoned the president's plan to rate colleges on their performance -- amid significant pushback from some college leaders and the realization by federal officials tasked with producing the system that they lacked much of the data they needed to do it right.

But as Obama prepares to ride off into the sunset, we gave college leaders the chance to turn the tables and grade the president himself on his performance on higher education.

They were not particularly kind.

First, the administration won modest support (it's all relative) for jettisoning its effort to rate colleges and instead publishing a slew of new data in a revamped College Scorecard.

In response to the statement "the College Scorecard is better than what I thought the Obama administration would produce when it first started talking about ratings," 31 percent of all presidents agreed and 36 percent disagreed, with 32 percent in the middle. Given how little college leaders thought of the original proposal -- 56 percent gave it a D or F grade in our 2015 survey of presidents -- that isn't saying a whole lot.

Other questions about the scorecard showed why presidents still aren't fans. Only 10 percent agreed or strongly agreed that the federal tool "accurately reflects my institution's strengths and weaknesses" -- 69 percent disagreed or strongly disagreed.

Sixteen percent of presidential respondents agreed or strongly agreed that the scorecard information about salaries and employment reflects their college or university accurately (58 percent disagreed), and just 11 percent agreed that it would "help students and their families make better-informed decisions about colleges."

Andrew P. Kelly, director of the American Enterprise Institute's Center on Higher Education Reform, said he was unsurprised by the skepticism about the usefulness and accuracy of the information in the College Scorecard, since there is widespread recognition -- even among researchers and advocates for more higher education accountability -- about the shortcomings of the data currently available to policy makers. Because many federal data sources track only limited groups of students -- such as those who receive federal student aid and first-time, full-time undergraduates -- the scorecard will present, at best, an incomplete picture of most institutions' performance.

But Kelly said it was difficult from the results to know how much of college leaders' disdain for the College Scorecard resulted from questions about the data, "and the extent to which they are inaccurate or misleading," rather than because they are "opposed to the overarching goal" of more accountability and better data about the performance of higher education.

"You're left to wonder who in this group of highly skeptical people are mostly concerned about the important technical issues, many of which could be ameliorated by better federal data collection, or about something more fundamental," Kelly said.

He noted that public universities, whose leaders offer somewhat less negative opinions about the scorecard in the Inside Higher Ed survey than is true of their private college peers, have generally expressed support for the Obama administration's broad goals, and have not -- like many private college leaders -- opposed efforts to expand federal data collection on student outcomes.

The College Scorecard was hardly the only policy issue on which private college presidents took the most negative view of the Obama administration's work on higher education, which has included an enormous infusion of federal funds into student aid programs from the 2009 stimulus forward, aggressive regulation of for-profit colleges in particular and institutions in general, and tough talk about rising prices and mounting student debt.

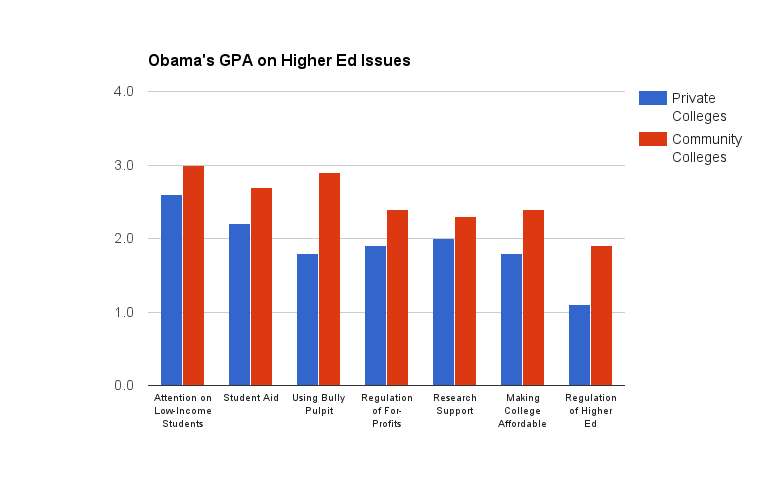

Given a chance to grade Obama on his overall treatment of higher education and a set of subissues (see table below), independent college chiefs gave him worse marks than public university leaders did on every single one. (Leaders of for-profit colleges, at which the Democratic administration directed most of its regulatory fire, almost surely would have taken an even more negative view, but they did not respond to the Inside Higher Ed survey in sufficient numbers for their answers to be broken out separately.)

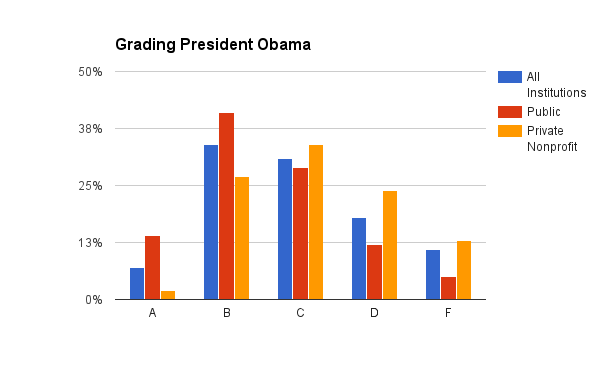

Over all, 7 percent of presidents gave Obama an A grade on his approach to higher education, 34 percent gave him a B, 31 percent a C, 18 percent a D and 11 percent an F. That averaged out to a 2.1 grade point average, or a C. Public college and university leaders scored him at 2.5, and those from private nonprofits at 1.8. Community college chief executives graded him highest of all, at 2.6, with 63 percent giving him an A or B.

Presidents graded Obama most kindly (2.7 GPA) on his efforts to focus attention on low-income students, and worst, by far (1.4 GPA, a D) on regulation of higher education. The gaps between public and private college leaders in their views of Obama varied from two-tenths of a point on research support (2.2 vs. 2.0 GPA) to almost a full letter grade (2.6 vs. 1.8) on "using the bully pulpit to promote higher education" and higher ed regulation (1.8 vs. 1.1 GPA). Community college leaders were the most supportive over all.

Analysts offered differing explanations for that gap.

David A. Bergeron, vice president for postsecondary education policy at the Center for American Progress and a longtime Education Department official, said he found the private colleges' criticisms "odd." Obama's "focus on balancing access, affordability and outcomes," he said in an email, "plays much more to [private colleges'] strengths than the normal lens we have put on the role of higher education on access and affordability -- areas where the nonprofits have traditionally failed. Generally, nonprofits do better on outcomes and so lifting those up should have made the nonprofits happy."

Bergeron also noted that most of the administration's attempts to crack down on higher education were aimed at for-profit colleges and states. "Those are the one group of institutions that the department left alone," he said.

Mary Nguyen Barry, a policy analyst at Education Reform Now, was harsher. "Many private colleges have been notorious for taking advantage of the information gap around college quality," she said via email. “Because no one knows what quality in higher education means or looks like, private colleges can portray ‘quality’ with flashy and expensive inputs like fancy buildings, lavish dorms, lazy rivers, sports, top faculty and smart students. But when the Obama administration came along to push the framework toward examining students' outcomes and the tangible results they get in exchange for their private and public investment, it's no surprise that private colleges are now some of the most ardent opponents to quality efforts like the College Scorecard. It's time that private colleges recognize that they're not exempt from federal oversight simply because they’re ‘private’ and not ‘public.’”

Sarah A. Flanagan, vice president for government relations and policy development at the National Association of Independent Colleges and Universities, which represents private nonprofit colleges, disputed the idea that her members are unwilling to be held accountable or are opposed to the administration's efforts to help students.

"Our institutions have deep, deep appreciation for what the president did for Pell Grants, which made a huge difference for their students, particularly in the middle of an economic downturn," Flanagan said in an interview. Under Obama, for the first time in many years, "we saw the stability of federal student aid, which became a constant and reliable source."

The frustration, she said, emerged from what she described as a "gap" between what the administration said it was trying to accomplish and "the solutions" it put in place, which created "a lot of unintended consequences." While Bergeron is right that independent colleges weren't the target of most of the administration's efforts (except some of its rhetorical critiques about high tuition and limited access for low-income students), Flanagan said, many of its initiatives, including those that sought to redefine the credit hour and require states to step up their oversight of colleges operating in their states, "missed the target and make it incredibly complex for our institutions."

"We found ourselves doing a lot of agreeing with the goals and aspirations of the administration, including a tremendous embracing of the idea that [student] completion should be the focus," she said. "But a lot of their intentions have translated into regulations that despite the good intentions, almost get in the way of the outcomes."

Community college leaders were on the opposite end of the spectrum from the private nonprofit college presidents in their assessments of Obama, who has championed two-year institutions rhetorically and with policy proposals on many occasions, even if he hasn't fully delivered on his promises in all cases.

While two-year-college leaders aren't fans of the College Scorecard -- they took the dimmest view of all postsecondary sectors of the new data system in this survey -- they gave the president by far the highest grades: 2.5 over all, 3.0 on attention to low-income students and 2.9 on using the bully pulpit to promote higher education. (And community college presidents hated Obama's regulatory approach the least, with only 32 percent giving him a D or F grade.)

Financial Confidence Rising Again

Many of the questions in this year's survey are tied to recent events, including the racial protests and the controversies over nontraditional presidents. Our surveys also strive to take the pulse of presidents over time on certain issues, like the economy. This year's survey, like those of recent years, asked some questions related to colleges' financial situations -- and the responses showed some modest optimism.

The survey asked campus leaders about the sustainability of their own institution's financial model over five- and 10-year horizons, and the answers showed growing confidence. As seen in the table below, nearly six in 10 presidents agreed or strongly agreed that they were confident in the sustainability of their college's financial model over five years, and 48 percent expressed such confidence over 10 years. Both of those numbers -- especially the latter -- were up over last year, but lower than they were in 2014.

The biggest increases from 2015 to 2016 in the confidence of individual sectors of higher education were for presidents of public master's/baccalaureate institutions (whose confidence over a five-year period rose from 43-45 percent in 2015 to 55 percent in 2016) and for private colleges generally: 65 percent of independent college presidents expressed confidence in their institution's sustainability over five years and 57 percent did over 10 years, compared to 61 and 44 percent, respectively, in 2015.

Sustainability of Institutions' Business Models

| 2016 | 2015 | 2014 | |

| Presidents' Confidence in Sustainability of Own Institution Over 5 Years | |||

| Strongly Agree | 25% | 20% | 26% |

| Agree | 34 | 36 | 36 |

| Disagree | 11 | 16 | 11 |

| Strongly Disagree | 3 | 5 | 4 |

| Presidents' Confidence in Sustainability of Own Institution Over 10 Years | |||

| Strongly Agree | 15% | 13% | 17% |

| Agree | 33 | 26 | 33 |

| Disagree | 18 | 23 | 16 |

| Strongly Disagree | 3 | 7 | 6 |

| Presidents' Confidence in Sustainability of Sectors' Business Models Over 10 Years | |||

| Public Flagship Universities | 67 | 51 | 64 |

| Nonflagship Public Colleges | 26 | 20 | 29 |

| Community Colleges | 37 | 34 | 45 |

| Elite Private Universities | 92 | 85 | 89 |

| Elite Liberal Arts Colleges | 81 | 71 | 72 |

| Other Four-Year Private Colleges | 15 | 10 | 16 |

| For-Profit Colleges | 7 | 16 | 19 |

Respondents were also asked to rate the sustainability of the business models of various groups of colleges and universities over the next decade, and not surprisingly, the wealthiest and most politically powerful institutions fared the best in their estimation.

Overwhelming majorities of presidents agreed that the business models of private universities with endowments over $1 billion (92 percent), elite liberal arts colleges with endowments of $500 million or more (81 percent) and public flagship universities (67 percent) were sustainable over 10 years.

There was a big drop-off from there to community colleges (37 percent, including just 31 percent of community college leaders themselves), nonflagship public four-year institutions (26 percent), other four-year colleges (15 percent) and for-profit institutions (7 percent).

Presidents Against Campus Carry

The last set of questions addressed by the survey related to the proliferation of state laws that limit colleges' ability to keep guns off their campuses, as many institutions have sought to do.

In general, presidents are vociferously opposed to these laws and critical of the legislators who support the measures. Just 4 percent of presidents agree that "allowing students to carry concealed weapons will protect students from potential harm."

Eighty-seven percent agree that "allowing students to carry concealed weapons will endanger students and faculty members."

And 85 percent of college leaders agree (62 percent strongly so) that "elected officials who favor campus carry laws do not understand the culture of higher education."