Free Download

Higher education is widely misunderstood by the public, struggling to enroll sufficient numbers of students from low-income backgrounds and likely to face significant disruption in the flow of international students because of the Trump administration's policies, college presidents widely agree.

But despite a tumultuous year in which many campuses have erupted with unrest and faced perilous financial pressures, most presidents perceive a positive racial climate on their campuses and are increasingly confident that their institutions are financially stable.

Those are among the key findings of Inside Higher Ed’s seventh annual Survey of College and University Presidents, published today on the eve of the annual meeting of the American Council on Education. The survey of 706 campus leaders was conducted by Gallup in January and early February, and many of the questions and answers explore the array of turbulent issues that have dominated campus conversations (and Inside Higher Ed headlines) in the wake of the highly contentious presidential campaign and election: immigration, race and political discord, to name several.

Among the findings:

- A majority of presidents believe the 2016 election exposed a disconnect between academe and much of American society. Nearly seven in 10 perceive that anti-intellectual sentiment is growing in the U.S.

- Sixty-three percent of campus leaders believe their institution will be financially stable over five years, and more than half (52 percent) express such confidence over a decade, up four percentage points from 2016.

About the Survey

Inside Higher Ed’s 2017 Survey of College and University Presidents was conducted in conjunction with Gallup. A copy of the report can be downloaded here.

Inside Higher Ed regularly surveys key higher ed professionals on a range of topics.

On March 28 at 2 p.m. Eastern, Inside Higher Ed Editors Scott Jaschik and Doug Lederman will present a free webinar on the results and take your questions. Sign up here.

The Inside Higher Ed survey of presidents was made possible in part by advertising from Cengage, Helix Education, Intellus Learning, Jenzabar, Rowan University and Ruffalo Noel Levitz.

- The vast majority of presidents describe the state of race relations at their own college as either “excellent” (20 percent) or “good” (63 percent). But more than three-fifths of presidents describe race relations at American colleges in general as “fair.”

- Just 12 percent of presidents strongly agree or agree that most Americans understand the purpose of higher education; half strongly disagree or disagree. And campus CEOs widely believe the public thinks that college is less affordable than it is and that colleges are wealthier than they are because of flawed understandings of college finances.

The Election and Its Aftermath

Surveyed after the transformative November election, college presidents were asked a set of questions about the aftermath of the contentious campaign and the potential effects of the Trump presidency.

On the former, nearly seven in 10 presidents concurred that the election revealed that "anti-intellectual sentiment is growing in the United States" -- 32 percent strongly agreed, and 37 percent agreed. A full two-thirds of presidents agreed (41 percent) or strongly agreed (25 percent) that "campus protests after the election" -- some of the more extreme of which included flag burnings and some squelching of speakers -- "have played into an image that higher education is intolerant of conservative views."

A majority of presidents (54 percent) agreed that the election had "exposed that academe is disconnected from much of American society."

More practically, respondents also expressed significant fears about how some of President Trump’s anticipated policies might affect higher education -- and some of the administration’s early actions have validated those concerns.

Three-quarters of presidents strongly agreed (54 percent) or agreed (22 percent) that Trump “does not accept the scientific consensus on many issues, such as climate change,” and a comparable proportion (75 percent) agreed that “undocumented students may lose the rights they gained during the Obama administration.”

In the six weeks since Trump took office, the administration appeared to crack down on communications by the Environmental Protection Agency and other government departments that work on climate issues, and as the administration prepares to release its first budget plan, science agencies are among those being targeted for cuts to help pay for a projected $54 billion increase in military spending.

And while the administration has not yet taken any action to reverse the Obama-era policy that gave temporary protection from deportation and renewable two-year work permits to young people who were brought to the U.S. illegally as children, the White House has toughened immigration enforcement in ways that signal diminished acceptance of those from foreign lands, including students.

Nearly three-fifths of presidents (58 percent) strongly agreed or agreed that because of the administration’s stance on immigration, “international students may be less likely to enroll at American colleges.” (The survey period concluded a few days after the administration imposed its initial ban on immigrants from seven heavily Muslim countries.) Early reports suggest that the flow of foreign students to the U.S. is beginning to slow.

It is too early to tell if some of the survey respondents' other predictions about the Republican-controlled government’s policies will pan out.

More than two-thirds of campus leaders (69 percent) said they expected the administration to water down the Obama-era regulations governing for-profit colleges, which, in answer to another question in the survey, two-thirds also said they favor (see below). The Education Department this week announced a delay in implementing the new rules to allow for further study but has not taken steps to formally reverse them.

And just under half of presidents (49 percent) said the “Republican Congress is unlikely to maintain current levels of support for programs on which my college depends,” with 25 percent disagreeing and another quarter unsure. While Trump has signaled his desire to slash domestic programs to pay for that massive increase in defense spending, some Republicans have joined Democrats in voicing support for some research and student aid programs that colleges hold dear.

Changes in Washington

Trump paid little attention to higher education during the campaign, and neither he nor his new education secretary, Betsy DeVos, has had much to say about campus issues since then.

But to the extent the Trump administration does engage in higher education policy making, its officials may well upend Obama-era policies that presidents favor -- and in one case it has already done so.

More than three-quarters of respondents to the Inside Higher Ed survey said they favored the Obama administration's 2013 decision to apply the anti-discrimination law Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972 to gender identity as well as gender. The ruling was seen as protecting the rights of transgender students in higher education as well as K-12, and prompted other legal challenges that sought to further expand those rights.

Last month, the Education Department reversed the Obama guidance, which DeVos and other administration officials argued would let such policy decisions be made (more appropriately, in their view) at the state level. The withdrawal of the guidance could result in changes in states that don't themselves have built-in protections for transgender students.

Presidents surveyed by Inside Higher Ed also expressed support for other Obama-era policies that are thought to be in the Trump administration's crosshairs. Roughly two-thirds of campus leaders expressed support for the Education Department's rules requiring for-profit and other vocational programs to prove they prepare graduates for gainful employment (favored by 67 percent of respondents) and requiring colleges to use a "preponderance of evidence" standard in evaluating charges of sexual assault by students (which 63 percent favor).

Presidents surveyed by Inside Higher Ed also expressed support for other Obama-era policies that are thought to be in the Trump administration's crosshairs. Roughly two-thirds of campus leaders expressed support for the Education Department's rules requiring for-profit and other vocational programs to prove they prepare graduates for gainful employment (favored by 67 percent of respondents) and requiring colleges to use a "preponderance of evidence" standard in evaluating charges of sexual assault by students (which 63 percent favor).

The former have been delayed; the Republican Party's 2016 platform called for revoking the 2011 guidance that mandated the latter, and many expect that to happen, but there has been no formal action to date.

Wary as they may be of the Trump administration, college presidents were far from wholly enamored of its predecessor -- and they hope the new powers in Washington will undo at least some of the Obama administration’s policies.

Nearly nine in 10 campus leaders, for instance, said they opposed last year's decision by the National Labor Relations Board to allow teaching assistants at private colleges to unionize -- a ruling that is likely to be undone when Trump begins to reshape the panel with his own appointees.

And while DeVos has said little to nothing about how she plans to approach higher education accountability, it’s a safe bet that she agrees with the more than two-thirds (71 percent) of college presidents who said they oppose the College Scorecard created by the Education Department under President Obama.

The Trump administration’s predilection for deregulation has been accompanied by reports that Liberty University’s president, Jerry Falwell Jr., will lead a task force focused on reducing red tape for colleges, and private institutions like Liberty hold deep antipathy for the College Scorecard and many other federal regulatory efforts.

While more than a third of public college presidents, and 45 percent of leaders of public doctoral universities, express support for the Scorecard, only 23 percent of private college presidents and 17 percent of private baccalaureate college leaders do so.

Racial Tensions? Not on My Campus

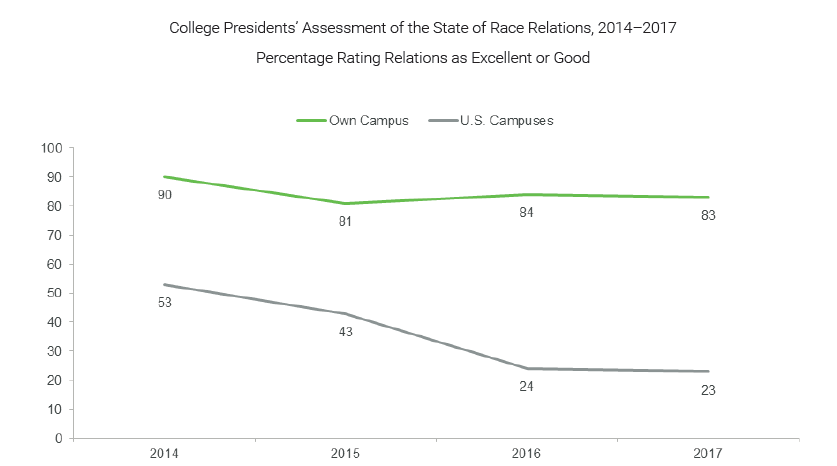

For several years now, Inside Higher Ed has been asking presidents to evaluate race relations on their own campuses, and also in higher education nationally. During that time period, higher education saw an upswing in the number and intensity of racial protests. And many campuses experienced tensions -- and some reported racial incidents -- in the aftermath of the 2016 presidential election.

But between 2016 and 2017, college presidents didn't change their views much about their own campuses.

By large majorities in 2017 (and every year they have been asked), college presidents view race relations on their own campuses as good or excellent. And this is the case even as only a minority say that about higher education nationally. (Most believe race relations on campuses nationally are only fair.)

This year, Inside Higher Ed also asked the presidents if reports of racial incidents had increased on their campuses since the election of Donald Trump. Twenty percent agreed or strongly agreed that they had. But 66 percent disagreed or strongly disagreed.

Shaun Harper, executive director of the University of Pennsylvania Center for the Study of Race & Equity in Education, said that he thinks the presidents are far too confident -- without much basis -- in race relations being good or excellent on their campuses. Harper studies race relations on campuses and consults with many institutions, conducting in-depth interviews with students and others on campus and reporting his findings. These types of discussions, he said, yield information that most presidents apparently miss.

"Unless there is a hate crime, black student protest or some other racial catastrophe on campus that garners national media attention, most college presidents erroneously presume that race relations are generally good," Harper said. "They fail to understand how racial inequities in student performance and persistence, as well as in employee promotion and retention, are symptomatic of pervasive racial problems. As they walk across campus, these presidents somehow fail to see and make honest sense of the often visible patterns of ethnic clustering among student groups."

He said his question for presidents is "How do presidents know that race relations are good on their campuses? Which data sources informed their responses to this particular survey question?" Lack of evidence doesn't mean all is well, he said.

In his experience doing actual individual interviews and focus groups on a wide range of campuses, race relations need to be recognized as troubled and in need of attention, Harper said.

A Misunderstood Enterprise?

The issue of campus diversity and inclusion is one of several on which college leaders believe the public doesn't understand what's really unfolding on their campuses.

About half of college leaders surveyed said they believed that the campus racial protests had "led many prospective students and families to think colleges are less welcoming of diverse populations than is really the case."

Even greater numbers of presidents believe the public misunderstands other aspects of what their institutions do. More than three-quarters of presidents believe that "attention to student debt" has led many prospective students and parents to believe college is less affordable than it is (84 percent agree), that an inordinate focus on the small number of institutions with large endowments has "created a perception that most colleges are wealthier than they are" (80 percent agree), and that the campus competition to provide student amenities has "contributed to the perception that these institutions have misplaced priorities" (76 percent).

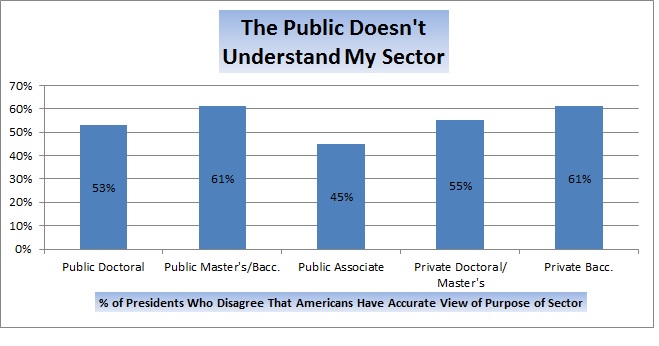

Roughly half of presidents also say Americans have inaccurate views of the purpose of higher education generally (50 percent) and of their sector of higher education (54 percent). Private college presidents were more likely than public university leaders to say that, as seen in the chart below.

Terry W. Hartle, senior vice president for government and public affairs at the American Council on Education, said in an interview that the perception gap between higher education and the public is a longstanding one. College presidents tend to view the purpose of a higher education as trying to help individuals "become educated citizens, be exposed to new points of view, to become lifelong learners," he said. "The public, often all they care about is jobs," Hartle said -- an "occupational focus" that has only intensified since the 2008 recession.

Layer on the resurfacing of another longstanding tension -- the culture-war undercurrent of higher education as a bastion of liberalism, which dates back decades to William Bennett in the 1980s and William F. Buckley's God and Man at Yale before that -- and you've got a recipe for conflict at a time of deep divisions in the country, Hartle said.

Alison Kadlec, senior vice president and director of higher education and work force engagement at Public Agenda, cites her organization's 2016 report "What's the Payoff?" to challenge the presidents' perspectives on the causes of the perception gap.

"A majority of Americans (59 percent) say colleges today are more like businesses and care mainly about the bottom line, versus 34 percent who say colleges today mainly care about education and making sure students have a good educational experience," Kadlec said via email. "Pessimism about the value of college is on the rise for the public, but people aren’t citing a misplaced focus on the building of lazy rivers and climbing walls as the source of their pessimism, nor do they seem to be relying on media depictions of debt when they describe what they view as the questionable priorities of colleges and universities.

"What we’re hearing is that the tight connection between education and socioeconomic mobility has been weakened for the public, and confidence in college as a certain path to economic security is waning," she added, noting that almost half of Americans see college as a questionable investment because of limited job opportunities. The threat of loan debt combined with uncertain career prospects seems to be at the heart of waning public confidence in higher education. Situate this uncertainty in the context of public concern that colleges and universities care more about their own bottom line than about students, and you’ve got a recipe for ongoing decline in public confidence in higher education.

"This is a constellation of public attitudes and anxieties that college leaders should be taking seriously."

Should Presidents Speak Out?

The 2016 presidential election and the start of the Trump administration have seen some presidents speaking out on political issues in ways that they haven't previously. The results of this year's survey of presidents suggest that presidents remain divided but that more of them -- yet not a majority -- may soon be speaking out.

In an April 2016 essay for Inside Higher Ed, Brian Rosenberg, president of Macalester College, wrote that the issues in the 2016 election represented such a challenge to academic values that it was wrong to stay silent. And Rosenberg has spoken out against some Trump administration actions -- particularly as they relate to international students -- in a tone that is more critical than is the norm for such statements from college leaders. He called the first version of Trump's travel ban on those from certain Muslim-majority nations "cowardly and cruel."

Rosenberg is not alone. Patricia McGuire, president of Trinity Washington University, used a blog post to criticize a Trinity alumna and donor, Kellyanne Conway, a top Trump aide. McGuire said that Conway has repeatedly distorted the truth -- echoing something many others have said, but unusually frank criticism for a college president.

While many academics have praised McGuire and Rosenberg, some college presidents have cautioned that there are dangers to political support for higher education if academic leaders are seen as partisan. In an essay this month in Inside Higher Ed, Donald J. Farish, president of Roger Williams University, wrote, "If college campuses are being targeted as the battleground between extremists on the left and right, then college presidents have to find ways to reclaim the middle ground. This starts with conversations between the institution’s administration and campus political groups and the creation of forums for debate between representative voices from left and right. A true debate, where students are invited to witness a meaningful presentation of opposing views, is far more interesting and useful than one-sided diatribes."

The results of the poll suggest that a minority of college presidents have been speaking out more than in the past, but that a large minority may be speaking out more during the years ahead than they have in the past.

Percentages of Presidents Answering Yes on Questions About Speaking Out

| Statement | All | Public | Private |

| Thinking about your own situation, did you, personally, speak out more on political issues during the 2016 presidential campaign than you typically do? | 31% | 34% | 27% |

| Have you spoken out more on political issues since the election than you typically do? | 33% | 37% | 29% |

| Regardless of how much you did speak out, do you wish you had spoken out more during the presidential campaign? | 16% | 20% | 12% |

| Are you now, or do you intend to, speak out more about issues beyond those that directly affect your college? | 45% | 45% | 45% |

Alison Byerly, president of Lafayette College, said she was heartened that presidents said they plan to speak out more. "The need for leadership within our communities at this time is palpable. The need for leadership in the public sphere is equally urgent," she said via email. "Public discourse is struggling to find a model for negotiating opposing views with civility, and conducting meaningful debate in the context of agreed-upon facts. Academia can either step up to provide that model, or retreat into the 'bubble' so often described by its critics."

Finances and Admissions

While political and cultural issues have dominated much of the recent conversation in higher education (and hence many of the survey questions), more mundane things -- like, oh, institutions' financial futures -- are front and center in presidents' minds.

The Inside Higher Ed survey once again asked presidents how they viewed their colleges' financial health -- the equivalent in higher education to a consumer confidence index.

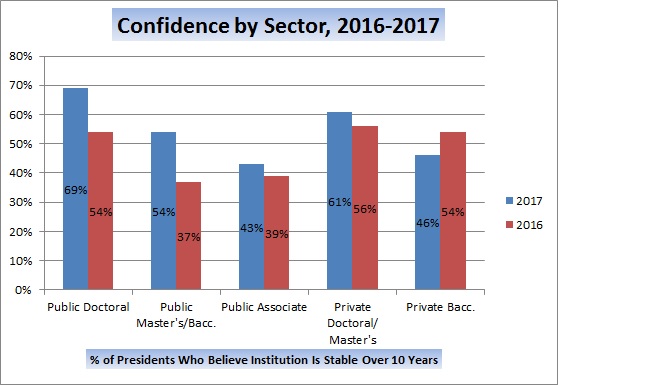

The state of presidents' confidence in 2017 is pretty good, and improving. Sixty-three percent of all presidents say they have confidence that their institution will be financially stable over five years (24 percent strongly agree, 39 percent agree) and 52 percent say so over 10 years. In both cases, the percentages are up by four points over last year.

Those numbers look very different by sector, though, as seen in the table below.

Presidents in all three public segments -- doctoral, master's/baccalaureate and associate-degree institutions -- have expressed continually rising confidence in recent Inside Higher Ed surveys, with particularly sharp increases for the four-year institutions (just 42 percent of public doctoral leaders and 33 percent of public master's and baccalaureate college leaders said in 2015 that their institutions would be financially sustainable over a decade).

The only sector in which presidents expressed much less confidence this year than last was the private baccalaureate colleges, perhaps resulting from the continued tumult around colleges such as Indiana's Saint Joseph's College and New York's Dowling College.

Institutions like those -- private nonprofit colleges without meaningful, let alone large, endowments -- were ranked by presidents as among the least likely (10 percent) to have a sustainable business model over 10 years, with only for-profit colleges (9 percent) scoring lower. About a quarter of presidents agreed that the business model of nonflagship public universities would be sustainable over a decade. By comparison, 91 percent of presidents said elite private universities with billion-dollar-or-greater endowments had a sustainable business model, as did 64 percent for public flagship universities.

At most colleges and universities, finances are closely linked to enrollments -- the other major topic addressed by the Inside Higher Ed survey. For some institutions, it's purely a numbers game -- do we have enough students (paying enough money combined) to meet our costs? For others, it's as much about the mix of students needed to achieve not just economic but also social and cultural goals.

Asked to rate how concerned they were about a dozen admissions-related issues, campus leaders expressed the most concern about "having enough institutional financial aid to enroll as many low-income students" as they would like and "enrolling students who are likely to be retained and graduate on time" (87 percent and 85 percent either very or somewhat concerned, respectively), followed closely by "enrolling my college's target number of undergraduates" (51 percent very concerned and 33 percent somewhat concerned).

Between half and two-thirds of presidents said they were very concerned about enrolling enough students who don't need institutional aid (26 percent very concerned, 38 percent somewhat concerned), more students studying online (15 percent very concerned, 43 percent somewhat concerned), enough racial and ethnic minority students to have a diverse student body (21 percent very concerned, 34 percent somewhat), and more international and first-generation students. Fewer than a third said they were concerned about enrolling classes that would improve their college's rankings.

Divisions by sector were significant. Private college presidents were much likelier than their public college counterparts to express concern about enrolling enough students who don't need institutional financial aid (82 percent vs. 44 percent), enrolling more out-of-state students (59 percent vs. 32 percent), and giving out too much aid to students who don't need it (66 percent vs. 34 percent).

Most of those public institution figures, however, were lowered by the inclusion of community colleges. When comparing four-year public and four-year private responses, the percentages were much closer: three in five public doctoral, master's and baccalaureate university presidents said they were concerned about enrolling enough students who don't need institutional financial aid, for instance.