Free Download

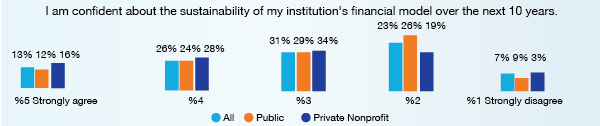

Fewer than 4 in 10 college presidents express confidence in the financial sustainability of their institutions over the next decade.

Less than a third agree that sexual assault is prevalent on American college campuses, and just 6 percent say it is prevalent at their own institution.

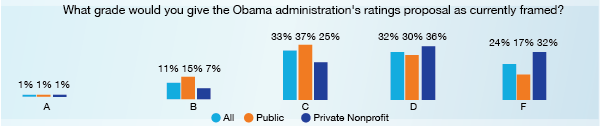

And campus leaders really don't like the Obama administration's proposed system to rate the performance of colleges, with more than half giving it a D or F grade when asked to turn the tables and rate the concept.

Those are among the findings of Inside Higher Ed’s fifth annual Survey of College and University Presidents, which is being released today in advance of this weekend’s annual meeting of the American Council on Education, higher education’s leading presidential association. A report of the survey's results can be downloaded here.

About the Survey

Inside Higher Ed's 2015 Survey of College and University Presidents was conducted in conjunction with researchers from Gallup. Inside Higher Ed regularly surveys key higher ed professionals on a range of topics.

On Monday, March 16, at 2:15 p.m. E.D.T., editor Doug Lederman and three campus leaders will discuss the survey's results at the American Council on Education's annual meeting in Washington. Details available here.

On Tuesday, April 14, at 2 p.m. E.D.T., Lederman and coeditor Scott Jaschik will analyze the findings and answer readers' questions in a free webinar. To register, please click here.

The Inside Higher Ed survey of presidents was made possible in part by advertising from Academic Partnerships, Jenzabar and Pearson.

A total of 647 college and university leaders from public, private, nonprofit and for-profit higher education institutions responded to the survey, which was conducted by Gallup Education, Inside Higher Ed’s survey partner. Presidents were granted anonymity to encourage candor, but their answers were coded by institution type, allowing for analysis of differences by sector.

Among the survey’s other key findings:

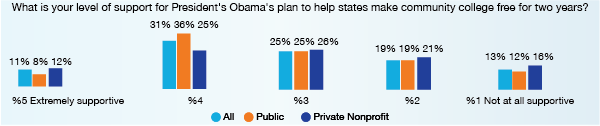

- College presidents are divided on the wisdom of President Obama's recent proposal to help states provide two years of community college tuition free. Not surprisingly, 68 percent of community college leaders support the idea, while just 20 percent of private nonprofit college leaders and about a quarter of public four-year college presidents do

- Fewer than half of chief executives describe the state of race relations in American higher education as excellent (1 percent) or good (42 percent). But 8 in 10 characterize the state of affairs on their own campus that way (18 percent excellent and 63 percent good).

- Most presidents want to be more involved in decisions about the hiring and tenuring of faculty members, and not to defer to the recommendations of faculty panels. (See related article.)

- Presidents are skittish about speaking out publicly about important issues, and skeptical about their impact when they do. Almost three-quarters (74 percent) agree that presidents "face significant risk if they take controversial positions" and half agree that they may offend trustees, donors and (for public college leaders) state leaders. And only one in five believes presidents have "real influence on public policy" when they express views on issues not directly related to higher education.

Perspectives on Politics

This has been a time of extraordinary federal activity in American higher education, and the survey sought to capture presidents' views on policy makers' concepts and their execution of the ideas.

It will probably surprise no one that presidents do not like the Obama administration's proposed college rating system; higher ed leaders have criticized the idea in many venues and forums since President Obama first mentioned it 19 months ago.

But support for the concept seems to be eroding rather than building as college leaders learn more about it (with the important caveat that there is still much more unknown than known about what the system might ultimately look like, if it ever emerges). Asked whether the Education Department's release of a framework aimed at fleshing out the ratings idea had helped or hurt their impression of it, 31 percent said they felt worse about the plan than they did before, and 11 percent said they felt better.

But few felt good. Given a chance to grade it, a third (33 percent) gave it a C, 32 percent a D and 24 percent failed it. Just 1 percent awarded an A grade and 11 percent a B. Just 10 percent agreed that the rating system, as currently conceived, would portray their institutions accurately.

Despite their overall disdain for the rating system, presidents differentiated among possible metrics for evaluating their institutions. Asked to weigh in on a set of measures that might be used in a rating system, almost half of campus leaders supported enrollment-related criteria such as percentage of first-generation students (49 percent) and percentage of Pell Grant-eligible students (48 percent), degree completion rate (47 percent) and net price (46 percent). About 4 in 10 backed the use of graduate employment rate (42 percent) and loan default rate (38 percent). They were much more skeptical about possible dependence on the federal graduation rate (29 percent) and graduate income level (18 percent) as criteria.

Nancy Zimpher, president of the State University of New York, said she understood her colleagues’ skepticism about the rating system, given that it’s a “really complex and hard thing to do” competently.

But she says higher education leaders may err by so regularly and consistently opposing outright federal efforts to give the public a way to compare the performance of colleges and universities. “We seem to have one speed -- 'let’s not do this,'” she says.

SUNY has been rare among colleges and higher education systems in offering general support for the concept while pointing out specific problems and suggesting practical improvements.

The pressure to hold colleges accountable for their performance and value has sustained itself through the last two presidential administrations, of different parties; there’s no reason to think it will fade, as college leaders seem to hope, Zimpher says.

Wouldn’t it be helpful, she adds, for higher education to try to coalesce around its own system of accountability and consumer information, rather than just being “stuck on no”?

Another federal initiative -- President Obama's free community college proposal – drew mixed reviews. Two-thirds of presidents (67 percent) agreed that the plan is likely to attract new students to higher education, a goal that virtually all of them would agree is worthy.

But about 7 in 10 presidents also agreed that the proposed program would draw students into community colleges and out of four-year universities -- and between a quarter and a half of presidents of four-year public and private nonprofit colleges (depending on type) said they believed the plan would lower enrollment at their own institutions.

Not surprisingly, the likelier presidents were to believe their own institutions would lose students under the president’s idea, the less likely they were to support it, as seen in the table below.

Views on the Free Community College Concept, By Sector

| Institution Type | % Believing the Plan Would Decrease Their Institution's Enrollment | % Who Say They Don't Support the Plan |

| Public Doctoral | 28% | 42% |

| Public Master's | 47 | 53 |

| Public Baccalaureate | 45 | 53 |

| Public Associate | 1 | 16 |

| Private Doctoral/ Master's | 49 | 70 |

| Private Baccalaureate | 37 | 60 |

Falling Confidence in Finances

Bad budget news is breaking out all over right now. Politicians in Arizona plan to end all state funding for two major community college districts, officials in states such as Louisiana and Wisconsin are weighing huge cuts in support for public higher education, and the pending closure of Sweet Briar College shocked many observers of independent colleges, as the institution is far from the most financially vulnerable in the sector, at least currently.

Fittingly, then, presidential confidence in their institutions’ financial futures seems to be on the decline.

Inside Higher Ed’s 2014 survey found that nearly two-thirds of presidents expressed confidence about the sustainability of their institution’s financial model over the next 5 years, and half did so over 10 years.

This year, the numbers fell to 56 percent over 5 years and 39 percent over a decade, as seen in the chart below.

And the table below shows that public institution presidents seemed to experience much bigger drops in their confidence than did their peers at private institutions.

Presidents' Confidence in Sustainability of Business Model Over 10 Years

| Institution Type | % Agreeing Model Is Sustainable Over a Decade, 2014 | % Agreeing Model Is Sustainable Over a Decade, 2015 |

| Public Doctoral | 53% | 42% |

| Public Master's | 56 | 31 |

| Public Baccalaureate | 50 | 34 |

| Public Associate | 44 | 36 |

| Private Doctoral/Master's | 48 | 42 |

| Private Baccalaureate | 45 | 41 |

Despite the year-over-year declines, several presidents interviewed said they still believed the presidents' assessments of their institutions' financial situations were overly optimistic.

Renu Khator, chancellor of the University of Houston System and president of its main campus, said the leaders' confidence probably stems "from their belief in the agility and adaptability of the university system" as a whole, which has found its way to adapt at various points in its history.

But Khator said she thinks many presidents are underestimating the impact of the "very serious disruption" that many institutions will see to their business models within a decade, "which will be more than we realize."

Patricia McGuire, president of Trinity Washington University, a private women's college in Washington, D.C., agreed that the responses may be overly rosy, which she attributed to presidents' disinclination -- even in an anonymous survey -- to acknowledge the severity of their situation.

"Presidents are paid to be boosters," she said. "And as I'm filling out this survey, I may be thinking, 'If I can't strongly agree that my college's business model is sustainable, should I be doing this job?'"

McGuire also noted that Sweet Briar's decision drew so much attention in higher education because it "wasn't about money, it was about enrollments" -- and "all of us are pretty fragile with enrollments these days."

As has been true in past iterations of this survey, presidents expressed the most confidence in the financial sustainability of the wealthiest institutions: private universities with endowments over $1 billion (85 percent agreed that those institutions' business models are sustainable) and elite liberal arts colleges with endowments over $500 million (71 percent), followed by public flagship universities (61 percent).

They expressed the least confidence in nonelite private four-year colleges, with just 10 percent agreeing that their business models were sustainable, for-profit colleges (16 percent) and nonflagship public four-year universities (20 percent). The sector enduring the biggest drop in confidence from 2014 to this year was community colleges, though, with 34 percent of campus leaders agreeing that two-year colleges had a sustainable business model, down from 45 percent a year ago.

Rose-Colored Glasses on Race

The survey's release follows by just a few days the conflagration at the University of Oklahoma over a fraternity's racist video, although of course they answered the survey before that video become public. Maybe that's why the presidents' answers to a set of questions about race seem more hopeful than accurate.

Eighty-one percent of college leaders said that the state of race relations on their own campus was either excellent (18 percent) or good (63 percent). Far fewer (43 percent total) said the same about race relations on college campuses in general. And those numbers are both lower than last year's survey responses, when 90 percent gave a thumbs-up to race relations on their own campuses and 53 percent to colleges and universities in general.

Even so, the answers struck commentators as -- well, let's let Trinity's McGuire say it: "They're kidding themselves."

"I run a majority black college," she said, but race can crop up any moment at Trinity just like at any campus, she said. "As Oklahoma illustrates, racial issues gurgle through informal student organizations all the time."

And even when the issues are not as severe as the clear-cut racism evident in that case, the self-segregation and racial tensions that underlie society are abundantly in evidence on campuses, she said.

"Even here among my students of color, they’re dissing each other all the time," McGuire said. "Saying we don’t have a problem, I think, is blind to how we relate to one another."

Sexual Assault

Colleges have been under intense scrutiny -- from Congress and the Education Department's Office for Civil Rights, advocacy groups, and the news media -- on their handling of campus sexual assaults. The survey asked campus leaders a broad set of questions about the topic -- and the answers suggest that presidents are unsure about just how big a problem they have and the viability of potential solutions to it.

Start with a basic premise put before the chief executives: "Sexual assault is prevalent at U.S. colleges and universities." Thirty-two percent agree, 26 percent disagree -- and 42 percent are right in the middle.

They are more confident that sexual assault is not a major problem at their own institution, of course, with 78 percent of presidents taking that view. And three-quarters strongly agree (24 percent) or agree (53 percent) that their institution is "doing a good job protecting women from sexual assault on my campus," and a full 90 percent say their campuses provide due process for those accused of sexual assault.

College leaders also express ambivalence about some of the approaches that regulators and lawmakers are pushing on them.

Fifty-seven percent of presidents say they support the federal government's requirement that in adjudicating sexual assault cases, they use a "preponderance of evidence" standard, which assumes a 50.1 percent chance that the accused is guilty of the charge, rather than guilt beyond a reasonable doubt. Forty-three percent of the respondents say the shift to the lower standard is not appropriate.

And respondents are skeptical that the "affirmative consent" approach legislated in California and increasingly adopted by colleges around the country -- which shifts the burden of proof by requiring those accused in campus sexual assault cases to show that their accusers had consented to sexual activity throughout -- will be effective. Twenty-seven percent of presidents said affirmative consent would not be effective at all, 44 percent said the standard would not be very effective, 27 percent said it would somewhat effective and just 1 percent said it would be very effective.

The results disappointed Laura Dunn, executive director of SurvJustice, a sexual assault prevention group. She said it was striking that fewer than three in five presidents supported the "preponderance of evidence" standard -- given that it's a federal government mandate. "I'm shocked that presidents aren’t on board with federal law," she said.

Dunn said that unlike the presidents, many of the campus student affairs professionals she works with like the idea of affirmative consent, because it's a "bright line to help make decisions," she said.

The fact that fewer than a third of chief executives believe campus sexual assault is a prevalent problem -- and that 1 in 17 sees it that way on his or her own campus -- troubles Dunn.

"I guess I'm not surprised, given their positions, that it's more about salesmanship than perhaps the true reality of the campus," she said.

Molly Corbett Broad, president of the American Council on Education, said it would be a mistake to read the presidents' responses as a sign that "our institutions of higher education are looking away from this issue."

She noted Grinnell College's recent decision -- without the threat of a pending investigation -- to ask the Office for Civil Rights to review its handling of sexual assault cases. "They're taking it very seriously," Broad said, "because none of them know precisely what the rules are that they need to be held accountable to."

Speaking Out

The death late last month of the Reverend Theodore M. Hesburgh, the legendary former president of the University of Notre Dame, renewed the time-honored discussion about why college presidents today do not seem to play the role of public intellectual and social issue heavyweight that higher ed leaders like Hesburgh, William C. Friday and Clark Kerr did a few decades ago.

The Inside Higher Ed survey may shed some light on that question, from the presidents' own perspective. About half (46 percent) agreed or strongly agreed that "presidents should speak out more on issues beyond those specifically germane to higher education"; only 22 percent disagreed or strongly disagreed.

But the answers also provided some evidence on why relatively few do. Nearly 6 in 10 respondents said they believe presidents "have real influence on public policy" when they speak out about higher ed matters, but just 21 percent said the same was true when campus chiefs comment on nonacademic matters.

Three-quarters of presidents also said that presidents face "significant risk" if they take controversial public positions on issues, and about half agreed that they might offend state officials or trustees and donors if they "speak out about important issues."

Broad of the American Council on Education said she understood that few presidents today can match the public visibility of the Hesburghs and Fridays. But she noted that many presidents participate on White House commissions, chambers of commerce in their local communities and the like.

"There are many different ways in which college and university leaders are contributing to major social issues -- maybe not in as visible a way," she said.

And academic leaders may not be cut out for the environment in which much of public discourse plays out today, she said.

"When you are living at a time when social media and 24-hour news coverage are the norm, and you have to make instantaneous judgments about how to respond," Broad said, "these are not circumstances that are comfortable given the kind of deliberation academic leaders tend towards."