You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

pressmaster/Pexels.com

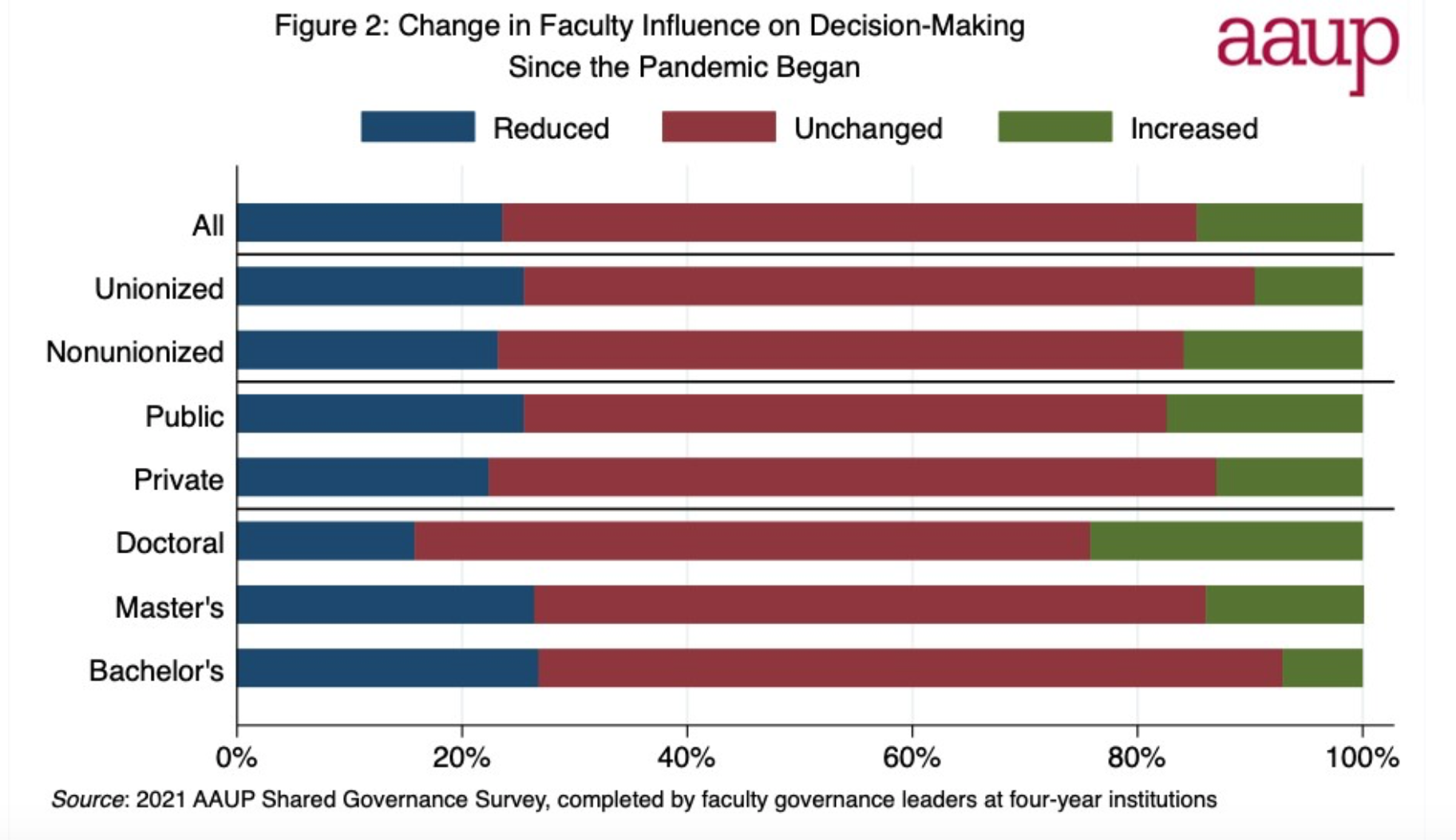

Nearly a quarter of faculty senate chairs say faculty influence at their institutions declined during the COVID-19 pandemic, according to a new survey of these faculty leaders by the American Association of University Professors. The finding supports the conclusions of a recent investigation by the AAUP into alleged violations of shared governance and faculty rights at multiple institutions over the course of the pandemic.

At the same time, the new survey of faculty chairs found what the earlier investigation, given its parameters, couldn’t: that some faculty chairs -- 15 percent, in this case -- reported an increase in faculty influence over the last year. That is, while some institutions responded to the challenges of COVID-19 by cutting off the faculty voice, others leaned in to it.

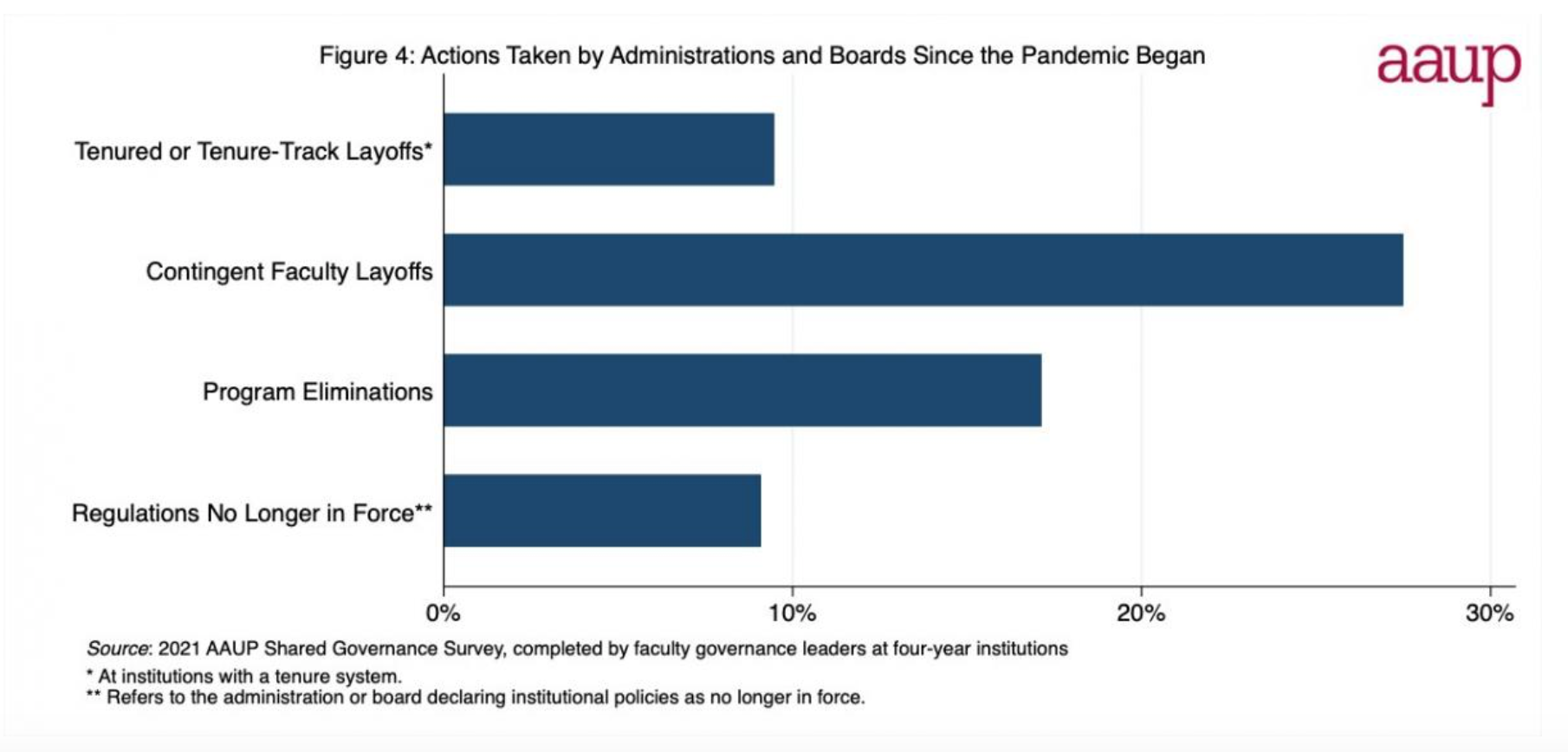

The AAUP survey also provides a clearer picture of how common particular administrative actions were during COVID-19, beyond the isolated cases the association recently investigated. Ten percent of faculty leaders at institutions that have tenure said their administrations laid off tenure-track or tenured professors, for instance.

With serious implications for academic freedom, 24 percent of respondents said they felt that faculty members could not voice dissenting views without this fear. This sentiment was especially common at institutions that voided faculty handbooks, contracts or other regulations during COVID-19.

Faculty Influence

Regarding general faculty influence, the AAUP asked survey respondents to rate how influential the faculty voice on their campuses had been in decision making both before and after the onset of the pandemic, from “not influential at all” to “extremely influential.” The largest change was in the “not influential at all” category, which increased from about 5 percent of the sample, pre-pandemic, to about 10 percent after the pandemic. Somewhat surprisingly to the AAUP, the second-biggest shift was in the “extremely influential” category, which increased from 5 percent to about 7 percent.

Looking at the bigger picture, 24 percent of respondents reported a reduction in faculty influence and 15 percent reported an increase. The majority of respondents said faculty influence remained unchanged. Faculty chairs at doctoral institutions were most likely to say their and their colleagues’ influence had increased, at 24 percent, compared to 14 percent of chairs at master’s degree-granting institutions and 7 percent at bachelor’s institutions. In comments, some respondents attributed a growing faculty influence to new administrators whose arrival coincided with the pandemic or other factors that were likely unrelated to COVID-19. But others reported that professors had fought for this influence given the gravity of the moment.

“While I would say our influence has increased, this is not because the administration is more interested in our input,” one chair wrote, for example. “It is because the decision making is so crucial and so much is at stake that faculty are considerably more vocal and persistent than in previous years and refuse to be ignored on health and safety issues.”

“While I would say our influence has increased, this is not because the administration is more interested in our input,” one chair wrote, for example. “It is because the decision making is so crucial and so much is at stake that faculty are considerably more vocal and persistent than in previous years and refuse to be ignored on health and safety issues.”

Professors have formed dozens of new AAUP chapters over the past year, according to the association.

Budgets, Tenure, Layoffs and ‘Force Majeure’

AAUP’s survey also asked about professors’ involvement in budgetary decisions during COVID-19. Just 3 percent of respondents said that the faculty and administration on their campus exercised equal influence in this area. Twenty-eight percent of respondents said there was an opportunity for “meaningful” faculty involvement in budgetary decisions. Sixty-nine percent said their administration acted unilaterally on budget issues. Again, faculty leaders at larger institutions -- those enrolling more than 5,000 students -- were more likely to report faculty involvement, or at least less unilateral decision making.

Regarding tenure, 10 percent of respondents whose institutions offered tenure said that tenured or tenure-track professors were terminated or not renewed during the pandemic. Some 28 percent of all respondents said that faculty members working on contingent or term appointments had been laid off.

Seventeen percent of respondents reported program eliminations since March 2020.

“Unsurprisingly, the apparent purpose of program eliminations is often to terminate the appointments of tenured faculty,” the AAUP observed, as 41 percent of chairs at institutions with tenure where program cuts happened reported layoffs of tenured or tenure-track faculty members. Only 3 percent of institutions where programs had not been eliminated reported such layoffs.

The AAUP’s recent investigation mostly looked into shared governance violations at small, private colleges. And while “much attention during the past year has been on small private liberal arts institutions engaging in program eliminations and layoffs,” the new survey report says, the survey found these actions were taken at “about the same rates at public and private; bachelor’s, master’s and doctoral; and unionized and nonunionized institutions.”

The AAUP’s recent investigation mostly looked into shared governance violations at small, private colleges. And while “much attention during the past year has been on small private liberal arts institutions engaging in program eliminations and layoffs,” the new survey report says, the survey found these actions were taken at “about the same rates at public and private; bachelor’s, master’s and doctoral; and unionized and nonunionized institutions.”

The survey report says the AAUP views “with particular alarm” recent instances of administrations or governing boards declaring faculty handbooks, contracts or other documents no longer in force, at times due to an invocation of “force majeure” or “act of God.” How common is this? Nine percent of respondents reported that their administrations or governing boards declared institutional regulations to be no longer in force.

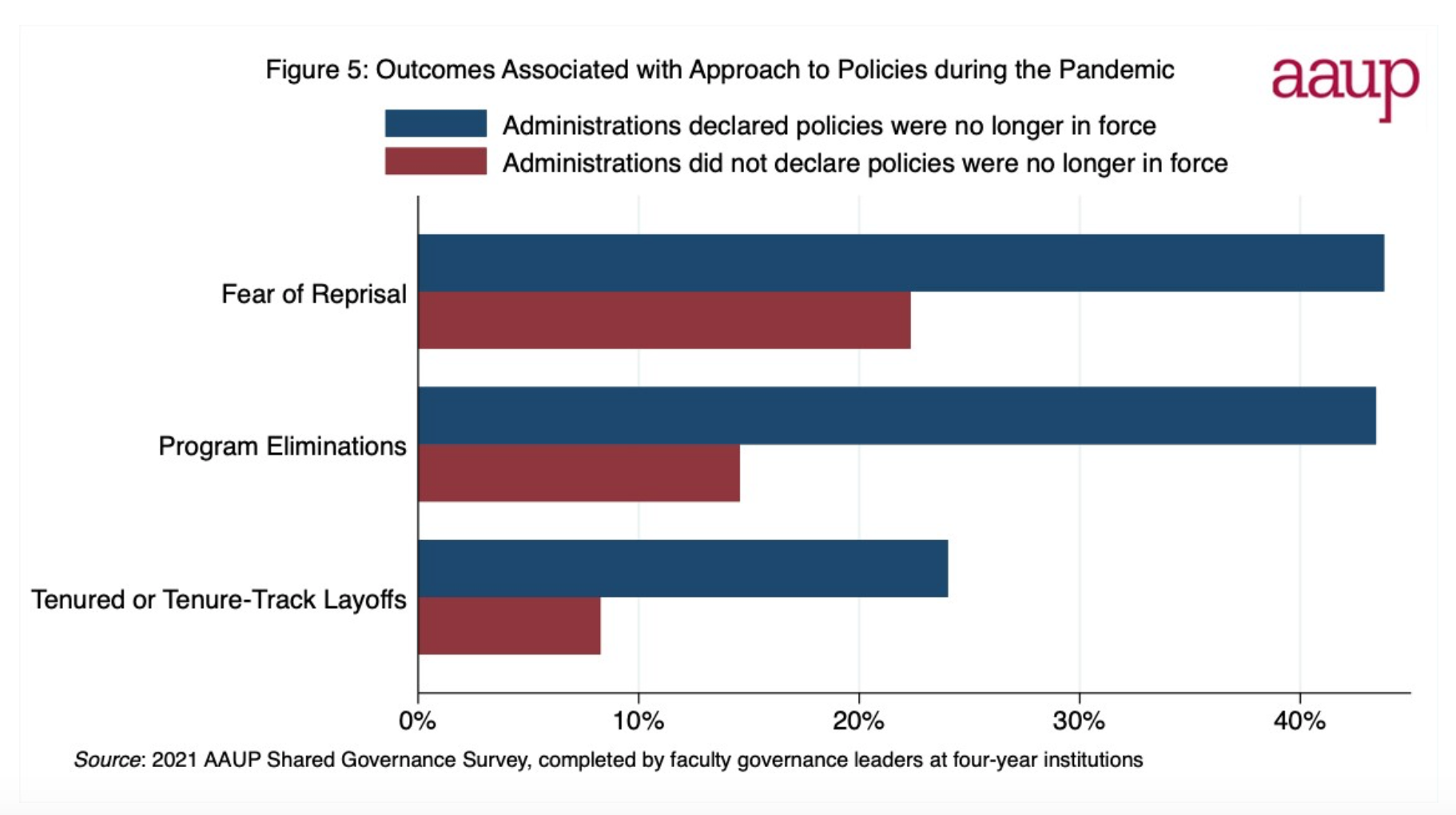

It’s “apparent that declarations that regulations are no longer in force are commonly used to effect program eliminations and terminations or nonrenewals of tenured or tenure-track faculty appointments,” the AAUP notes. The evidence: at institutions where regulations were voided, 43 percent of respondents reported the elimination of programs, compared to 15 percent of respondents at institutions where regulations had not been voided. Similarly, the AAUP says, at institutions with tenure regulations and voided regulations, 24 percent of respondents reported the termination or nonrenewal of tenured or tenure-track appointments, compared to 8.3 percent reported by those at institutions where no force majeure was declared.

Checking in on another metric of healthy shared governance, the AAUP asked to what extent faculty members can voice dissenting opinions without fear of administrative reprisal. Almost a quarter of respondents said they felt that faculty members couldn't voice dissenting views without this fear.

The AAUP links this feeling, in part, to force majeure. At institutions where the administration or board declared regulations no longer in force, 44 percent of respondents said that professors could not voice dissenting views without fear of administrative reprisal. That’s compared to 22 percent at institutions where no regulations had been voided.

Even at institutions where respondents reported an increase in faculty influence, 14 percent indicated professors are not able to voice dissenting views without fear of administrative reprisal. This was compared to 24 percent at institutions where faculty influence was unchanged and 31 percent at institutions where it had decreased.

Even at institutions where respondents reported an increase in faculty influence, 14 percent indicated professors are not able to voice dissenting views without fear of administrative reprisal. This was compared to 24 percent at institutions where faculty influence was unchanged and 31 percent at institutions where it had decreased.

“Shared academic governance has been under severe pressure since the onset of the pandemic,” the survey report says, quoting the AAUP’s investigation. On the other hand, the survey says, the findings about increased faculty influence “complement those of the governance investigation in a different way, as they point to ways in which faculties were able to respond successfully to the challenges of the pandemic through shared governance channels.”

Reiterating the investigation’s conclusions, the survey says that the survival of shared governance depends on a “conscious, concerted and sustained effort” by governing boards, administrations and faculties.

More Data to Come

This is the AAUP’s first faculty survey of shared governance in two decades. The association collected additional data but released those about the impact of the pandemic first.

Hans-Joerg Tiede, the AAUP’s research director, said the survey is representative of what faculty senate chairs and professors who hold similar positions are seeing across academe, in that he recruited a representative sample of 585 chairs with a response rate of 68 percent.

Over all, he said, “the survey provides evidence that the sorts of things that our recent investigation uncovered are not limited to the few institutions that were investigated, but that there is a broader trend when it comes to layoffs, declaring handbooks no longer in force and program eliminations.”

Adrianna Kezar, Wilbur Kieffer Endowed Professor and Dean's Professor of Leadership at the University of Southern California, recently contributed to a National Academy of Sciences panel report about institutional responses to COVID-19 and gender equity. Citing data from the Collaborative on Academic Careers in Higher Education at Harvard University, Kezar in that report said that faculty members generally gave their administrations high marks early in the pandemic, due to their quick action on campus shutdowns. As COVID-19 progressed, Kezar wrote, professors increasingly registered “concerns of being left out of decision-making processes for months, particularly on decisions that shape domains of teaching and learning, but also more broadly to significant decisions about program closures, finances and layoffs.”

Kezar’s other research suggests that during a crisis, leaders who “emphasize empowerment, involvement and collaboration allow themselves a greater degree of agility and innovation than is possible with an inflexible hierarchical leadership paradigm.”

Despite the AAUP’s finding that shared governance had increased in some places, Kezar said Wednesday that the overall trend “was more away from shared governance.” Yet there were, and are, “some institutions that I would say had quote-unquote enlightened leadership, and did lean in to seeking out faculty advice.”