You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Bachelor’s degrees conferred to English majors are down 20 percent since 2012, but responsive departments that know how to market their worth to students are finding ways to thrive, says a new analysis from the Association of Departments of English, or ADE. The group, which is part of the Modern Language Association, says its report is the most comprehensive study of English departments to date.

“While declines in the number of undergraduate majors have affected English departments widely and at all types of institutions, most departments are exploring ways to respond,” reads “A Changing Major: The Report of the 2016-17 ADE Ad Hoc Committee on the English Major,” released today.

A Comprehensive Overview

“We recommend that departments continue and share with each other (for example, through ADE) their experiments and innovations in addressing the enrollment downturn,” the committee wrote. “Constructing and presenting a new major well can be one step among others that departments take to reverse enrollment losses; ongoing monitoring and refining of the major are also important.”

Key to departments’ success will be reviewing and revising programs in terms of “the interest that study in English can hold for students, bearing in mind conditions that influence their learning,” the report says, “from digital reading and writing environments to employment concerns.”

Kent Cartwright, professor of English at the University of Maryland at College Park and chair of ADE’s ad hoc committee that wrote the report, said this week that he and his colleagues reviewed English programs at every type of four-year institution in preparing their report. Over all, they were impressed by what Cartwright described as the “continuing intellectual vitality of the major, which has served historically as an incubator of new programs,” and which has been “central to the intellectual and cultural life of our colleges and universities.”

As for the drop in majors, Cartwright said his committee realized that overhauling programs was not “the panacea for solving the problem of enrollment declines.” But they did “become convinced that it could be a component in a set of approaches,” he said.

Committee members also said that programs that “articulated their mission and presented themselves engagingly to students were doing, on the whole, better than some other programs.”

What the Data Say

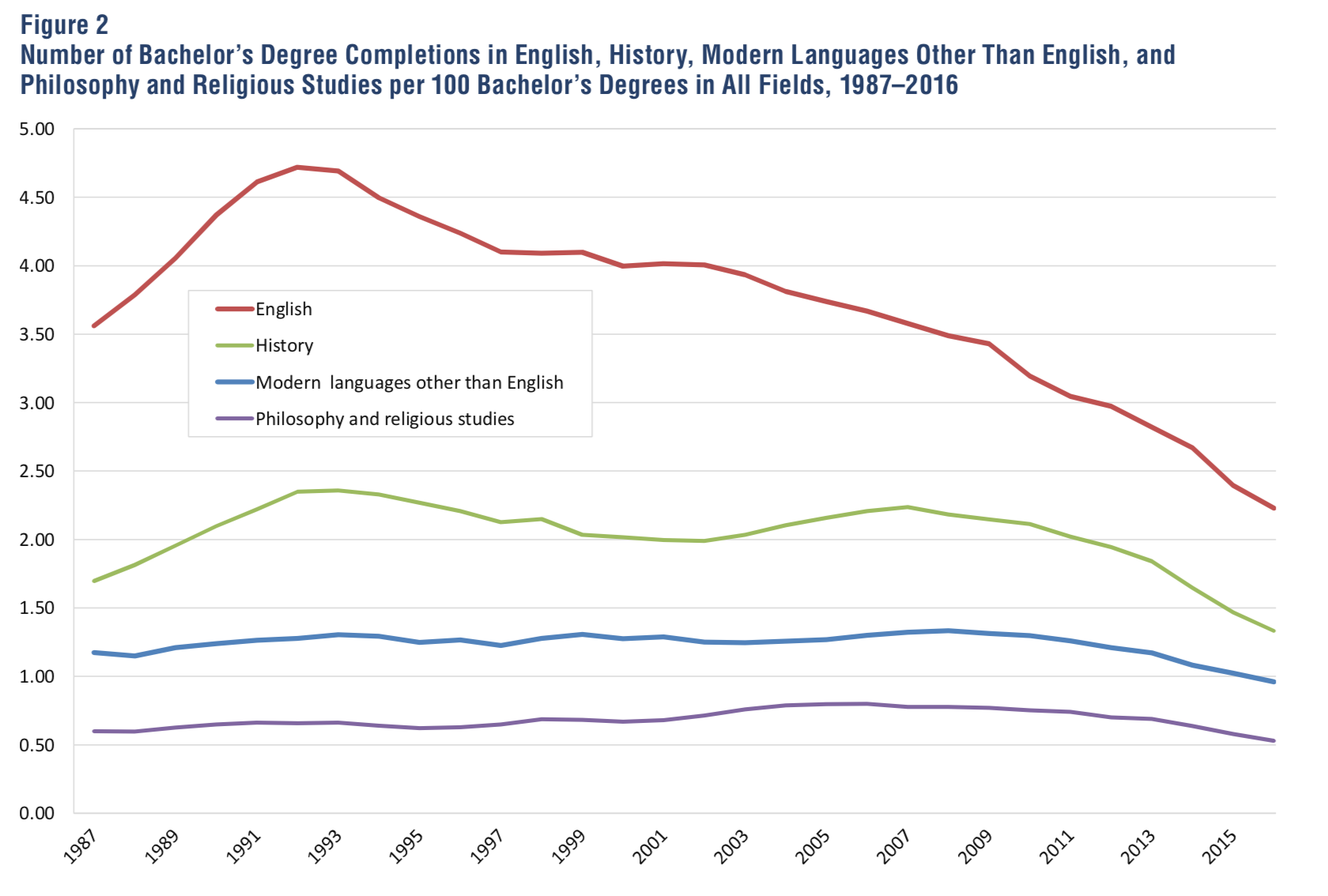

From 1991 to 2012, humanities bachelor’s degrees enjoyed a period of relative stability, according to the report, which drew on data from the National Center for Education Statistics. During that time, the number of bachelor's degrees in English averaged about 52,684 per year. But the number of degrees awarded in English has fallen each year since 2012, to the lowest point since 1989: some 42,868 degrees in 2016, the most recent year for which data were available.

ADE’s report notes that other humanities fields have suffered the same downward trend.

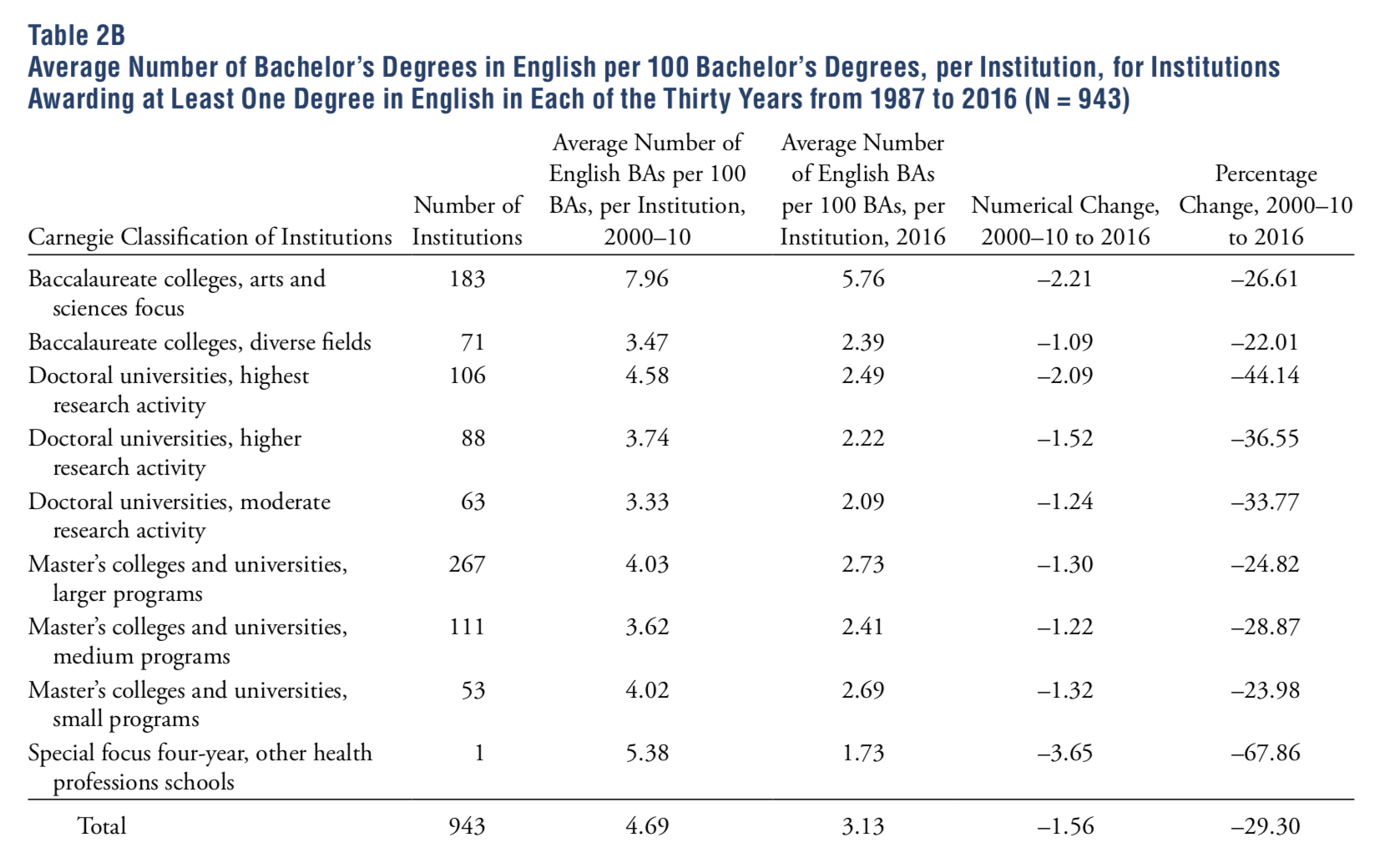

Over the same 30-year period, the number of degree completions in all fields steadily increased. So in terms of what the report calls “market share,” as measured by the number of bachelor’s degrees in English per 100 bachelor’s degrees over all, English has been on the decline since 1993. The steepest declines in English degrees were seen at baccalaureate institutions and doctoral institutions with the highest research activity.

ADE’s committee also surveyed member departments (excluding community colleges) about their majors. Some 539 departments were canvassed and 95 responded, anonymously, at a rate of about 18 percent.

Over 70 percent of responding departments said they’d either revised their undergraduate majors since 2010 or were currently doing so. Departments at private baccalaureate institutions were especially likely to have overhauled their majors.

Two-thirds of responding departments reported a decrease or sharp decrease in majors since 2010, with baccalaureate institutions most likely to say so. Just 9 percent of departments reported an increase in majors.

Tracks to Success?

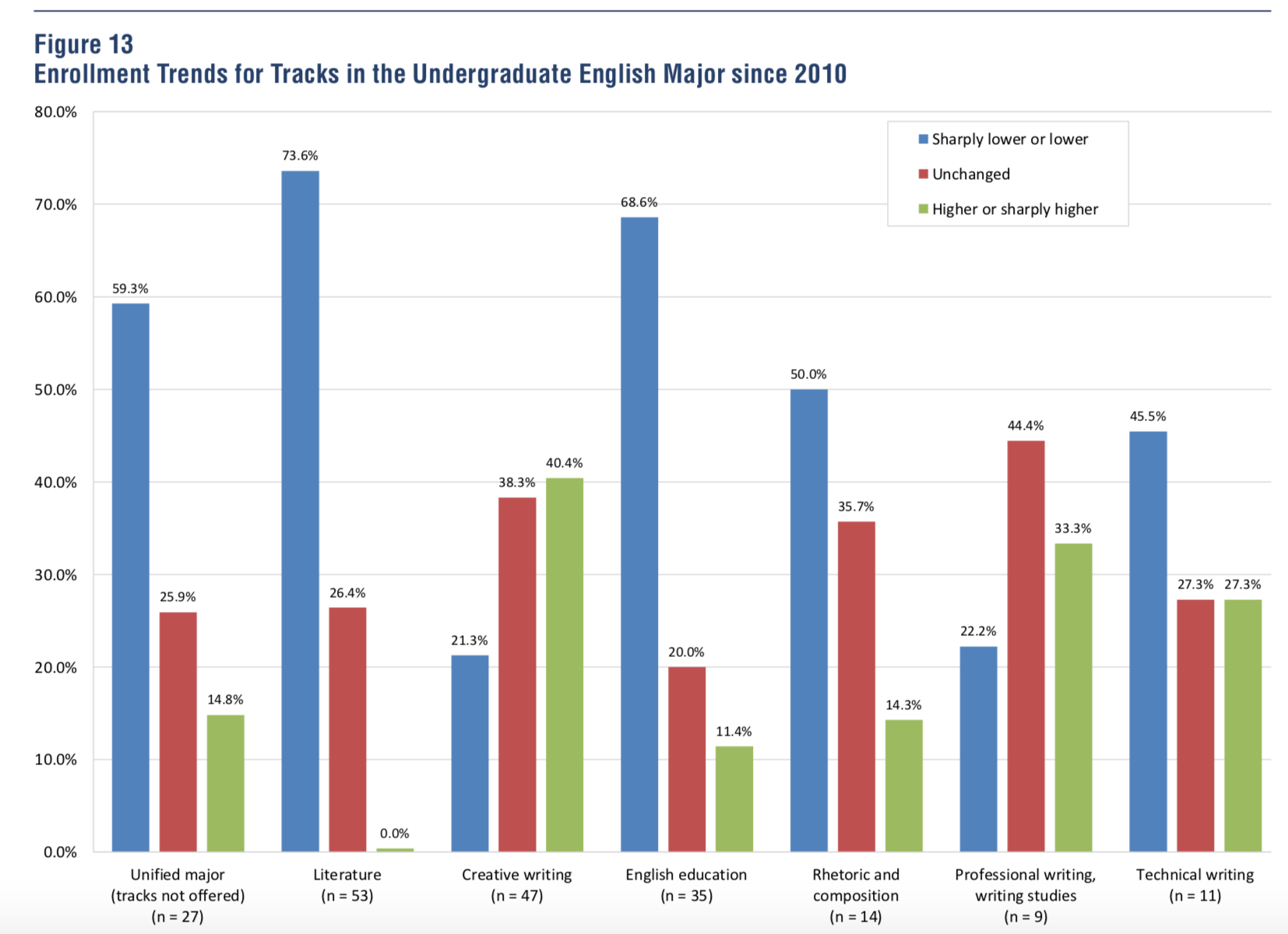

A majority of departments offer different tracks or concentrations through the undergraduate major, according to another part of the analysis. The most common are literature, creative writing, English education, rhetoric and composition, technical writing, and professional writing or writing studies. The report calls the number of departments featuring professional writing or writing studies “notable,” since it was not listed on the questionnaire but rather written in by respondents. Ph.D.-granting departments are somewhat less likely than the overall sample to offer English education and somewhat more likely to offer creative writing. Technical writing is less available in bachelor's degree-granting departments than in master’s and doctoral degree-granting departments.

Public institutions were more likely to offer different tracks, which the report attributes to these campuses having more teaching resources.

Creative writing and other writing specializations were the mostly likely tracks to see increased or unchanged enrollments. In contrast, literature tracks experienced decreases in 74 percent of departments, followed by English education (69 percent).

About one-third of departments reported having a unified major, without tracks. Of those, 60 percent reported declines in the number of students declaring English as a major. About 15 percent reported increases.

The courses most commonly required of all majors are a writing-intensive course (required by 72 percent of responding departments), an introduction to literature (72 percent) and a capstone seminar (62 percent), the report says. Surveys of British and American literature are required by more than half of responding departments, respectively. A course focused on literature before 1800 is required by 58 percent.

Fifty-four percent of the responding departments said they require 11, 12 or 13 courses for majors. The average is 12.

Experts’ Takeaways

Cartwright said that departments might do well to think about the study of literary history within the major since, in many cases, “historical requirements have contracted or been loosened.” And while almost every department says it requires some sort of literary history, many faculty members prefer to teach cultural history, he said.

The committee also noticed and encourages the rise of the study of Anglophone literature, the treatment of “media studies” in English departments, the trend toward digital components to the curriculum and the introduction of career-preparation modules, he said.

English is in fact a “changing major,” and the “problem for any department is to encourage liveliness, inquisitiveness and range, while also mounting a curriculum that has sufficient focus,” Cartwright said.

Paula Krebs, executive director of the MLA, said her takeaways from the report include the “increasing importance of writing in the English major,” meaning composition, rhetoric, professional writing and creative writing.

Departments are increasingly working to "integrate writing and digital and media studies with the more traditional focus on literary studies," to make the English programs "more capacious," she said. Some departments are going to tracks within the major, and others have concentrations, but all are “conscious that we must be more explicit about the value of the major for students after they graduate.”

That value comes from the “content, skills and perspectives that come with advanced study in the field, no matter what the concentration,” she said.

“Why Study English?”

Krebs’s comments echo a major conclusion of the committee’s report: that departments have no choice to but appeal to students’ concerns about employment postgraduation, and that they may do so by stressing certain aspects of the major.

On the whole, departments are using introductory statements on their websites to respond “straightforwardly to the current crisis in enrollments, often with a headline such as ‘Why Study English?’” the report says. “The answers to this question might be roughly grouped into three categories: skills, career prospects, and disciplinary content.” And other recent data suggest that humanities graduates are actually doing just fine.

As for skills, the report says that virtually every English department promises to develop students’ skills in reading, critical thinking and writing, and that many add a fourth skill, research. Concerning careers, almost all departments emphasize the range of good jobs and careers available to English majors.

Source: University of California, Davis

The committee says that describing the content of the English major in a “crisp and effective way is the most challenging aspect of website overviews.” But the task is made easier for those majors that are organized into a limited number of strong tracks or concentrations. Literary history is the most common curricular framework through which the major is advertised.

Beyond that, departments vary. Some emphasize the “freedom students are given to carve out an integrated course of study,” the report says. Others prefer to showcase pedagogical values, such as small classes and good teaching. “Still others indicate various lines of organization in the major, sometimes by articulating major curricular groupings: for example, forms and genres, regional and historical contexts, and theories of cultural and literary analysis.” The “cultural centrality of narratives or stories” is sometimes invoked, as is the idea of “media.”

An alternative tactic might be to ask, “What are the big and inspirational questions in literary study? What are the possibilities that animate the field and constitute its justification?” the committee notes.

More on Where the Major is Going

The committee also studied more than 100 departments’ websites to glean more information about where the English major is going. Many findings from that portion of the study parallel the ADE survey results. But the website-based program analysis also revealed a trend toward one or two required introductory courses to the major, given the historical shift away from common syllabus survey courses. Such introductory courses “involve considerable discipline-specific writing, and they train students in close reading and in methods and theories,” the report says. It seems to encourage the two-course model, saying that because “the survival of the English major depends on reading habits and skills, understanding and cultivating them are of paramount importance.”

Another trend among departments is to frame the English program not just as a program in literature but “more expansively as one in English studies, a term intended to show self-aware hospitability to media, composition, rhetoric, film, cultural studies and other interests that reside in English departments at all types of institutions,” the report says. Yet it notes a lack of focus thus far on new media and digital literacy.

“What may be surprising is the extent to which departments have not made digital and media studies visible parts of the major or the curriculum,” the committee wrote. “Their absence from English departments may be attributed to their presence in other departments or to difficulties in staffing. For digital studies, skepticism still lingers in some quarters about the field’s usefulness.”

Yet there is “no doubt that electronic and other new media loom large in the landscape of reading, writing, editing, design, and (increasingly) literary study and that training in digital and related studies can only enhance students’ employment prospects,” the report says. To that point, the committee wrote that one of the most interesting developments in various programs is the emergence of career-oriented courses, modules, internships and even concentrations, including professional writing.

The most obvious trend in revisions of the major, meanwhile, is the shrinking requirements in literary history, the traditional backbone of the discipline, the committee wrote. That’s especially true at doctoral institutions. But instead of shying away from these courses, departments might adopt "foundational courses that pose basic questions about periodization, especially how an age’s forms and paradigms give shape to human experience and knowledge,” the report says. Departments might also “experiment more than they do at present with teaching periods comparatively through themes or cultural topics. More courses comparing modes or writers from different periods might also be a vehicle.”

The study of language, especially tropes and figures of speech, also deserves attention, the report says, as do “values,” or the capacity of literature to influence people’s lives. What about Shakespeare? The committee found that departments at Ph.D.- and bachelor’s degree-granting institutions have tended, in some instances, to replace a required Shakespeare course with Shakespeare as an option within period distribution requirements. Shakespeare remains a requirement at more master’s degree-granting institutions, however, likely due to these campuses’ training of teachers. Poetry, meanwhile, is well represented in departments across institution types.

Programs’ diversity requirement has often come to include not only African-American literature but also that of other ethnic groups, along with literature of gender and sexuality, postcolonial literature, and even early literature, the report notes. One of the strengths of English programs has been their “championing of African-American literature in particular,” the report says. And courses in postcolonial or anglophone or global literature, if not folded into diversity requirements, “offer valuable global cultural insight.”

Keeping Focus, Showcasing Variety

Over all, the committee wrote, “The challenge is to keep focus while still showcasing variety. In our investigations, furthermore, those programs that have been able to present what they do in imaginative, catchy, and compelling terms appear generally to have suffered less than others have from enrollment declines.”

Some departments have reversed the downward trend and rebuilt enrollments, the report says. The Ball State University English program, for example, employs a track system of literature, creative writing, rhetoric and writing, and English studies, and has made “skillful use” of its website -- especially its blog, Ball State English -- along with social media, internships, and individualized contacts with prospective students to reverse its loss of majors.

“Departments can improve their situations, it would seem, through a clear and imaginatively presented major, especially when combined with active outreach and the creative use of new media,” the committee reiterated.