You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Stanford University

Since its inception nearly 47 years ago, the Stanford Prison Experiment has become a kind of grim psychological touchstone, an object lesson in humans' hidden ability to act sadistically -- or submissively -- as social conditions permit.

Along with Yale University researcher Stanley Milgram’s 1960s experiments on human cruelty, the August 1971 experiment has captured Americans’ imaginations for nearly half a century. It is a long-standing staple of psychology and social science textbooks and has been invoked to explain horrors as wide-ranging as the Holocaust, the My Lai massacre and the Abu Ghraib prisoner-torture scandal.

But new interviews with participants and reconsideration of archival records are shedding new light on the experiment, questioning a few of its bedrock assumptions about human behavior.

Perhaps most significantly, one of the “prisoners” now says his actions have long been misunderstood.

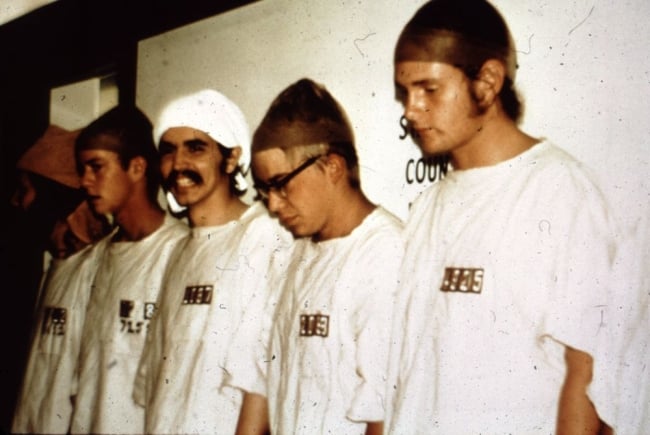

For the experiment, Stanford University psychology professor Philip Zimbardo built a three-cell mock “Stanford County Jail” in the basement of the university’s psychology building. His researchers housed nine “prisoners” and hired nine “guards,” all of whom had answered a classified ad looking for participants for a two-week study on prison life.

But just 36 hours into the experiment, prisoner Douglas Korpi found himself in lockdown, sealed into a closet repurposed as a makeshift solitary confinement room. He soon experienced what has been described as a mental breakdown.

It was one of the most visceral moments from the experiment, and it was caught on audiotape, with Korpi screaming, “I'm so fucked-up inside. I feel really fucked-up inside. You don't know -- I gotta go, to a doctor. Anything! I mean, Jesus Christ, I’m burning up inside, don’t you know? I can't stay in there. I'm fucked-up! I don't know how to explain it. I'm all fucked-up inside! And I want out! And I want out now!”

Korpi now says his episode was less a psychotic break than a manipulation so he could go home and study.

“Anybody who is a clinician would know that I was faking,” he told author Ben Blum in a rare interview last year, part of a lengthy feature in the online publication Medium. Now a forensic psychologist in Oakland, Korpi characterized his outburst as “more hysterical than psychotic.”

Actually, he screamed not because of abusive guards but because he was worried about not getting access to textbooks during his “prison” stay so he could cram for the Graduate Record Examination.

Korpi said he took the $15-per-day job as a prisoner because he thought he’d have time “to sit around by myself and study for my GREs.” The prison study, scheduled to last two weeks, lasted only six days after Zimbardo’s girlfriend, Christina Maslach (now his wife of many years), persuaded him to shut it down.

But when Korpi, who was scheduled to take the GRE just after the study concluded, asked for his books, guards refused. After unsuccessfully faking a stomachache, he faked the breakdown.

The admission is similar to one he gave the Los Angeles Times in 2004, when he said, "Zimbardo thought I was losing it."

Looking back on the experience, he told Blum he actually enjoyed himself most of the time, including during a brief prisoner “rebellion.”

“The rebellion was fun,” he said. “There were no repercussions. We knew [the guards] couldn’t hurt us, they couldn’t hit us. They were white college kids just like us, so it was a very safe situation.”

He was, however, shocked that he couldn’t leave of his own free will, remembering that the guards were “really escalating the game by saying that I can’t leave. They’re stepping to a new level. I was just like, ‘Oh my God.’”

In an interview, Zimbardo told Blum that the subjects “really believed they can’t get out,” but said they’d signed informed-consent forms that included an explicit “safe” phrase: “I quit the experiment.” Saying the phrase, he said, would earn an exit from the experiment.

Blum notes that the forms, dated August 1971 and available online at Zimbardo’s website, contain no mention of the phrase “I quit the experiment.” They do, however, consent to “a loss of privacy,” among other conditions. The forms note that subjects were expected to participate “for the full duration of the study,” and that they’d only be released for reasons of health “deemed adequate by the medical advisers to the research project or for other reasons deemed appropriate” by Zimbardo.

Blum’s revelations come weeks after the release of Story of a Lie, a new book by French academic and filmmaker Thibault Le Texier, who examined newly released documents from Zimbardo’s Stanford archives. He calls the experiment “one of the greatest scientific deceptions of the 20th century.”

In a tweet posted last week, University of California, Davis, psychology professor Simine Vazire wrote, “We must stop celebrating this work. It’s anti-scientific. Get it out of textbooks.”

In a statement issued Monday, Howard Kurtzman, acting executive director for science at American Psychological Association, said Blum’s Medium article “raises important questions about the Stanford Prison Experiment, many of which have been raised before.” He gave credit to Zimbardo for speaking to Blum and said the researcher “has responded to these questions over the years.”

Psychology textbook authors who address the study “would be well advised to place it in context, including the controversies around its methods and what it teaches us about the importance of institutional review boards, peer review and replicability,” Kurtzman said.

Dave Eshelman, a Stanford “guard” who earned the nickname John Wayne for his imaginative cruelty, told Blum he saw the experiment “as a kind of an improv exercise” that he wanted to perfect “by creating this despicable guard persona.” He has long maintained that he developed the cruel character after watching the movie Cool Hand Luke.

Eshelman said he tapped into his own experiences in a brutal fraternity hazing a few months earlier. Nearly half a century later, he recalled feeling “like I had accomplished something good because I had contributed in some way to the understanding of human nature.”

In a 2011 interview published in the Stanford alumni magazine, Eshelman said, “I set out with a definite plan in mind, to try to force the action, force something to happen, so that the researchers would have something to work with. After all, what could they possibly learn from guys sitting around like it was a country club?”

In a way, Eshelman said, he was running his own experiment within an experiment, each day trying to do something “more outrageous” than the day before. He often wondered “how much abuse will these people take before they say, ‘knock it off’? But the other guards didn't stop me. They seemed to join in. They were taking my lead. Not a single guard said, ‘I don't think we should do this.’”

Another guard, John Mark, told the alumni magazine that Zimbardo “went out of his way to create tension,” with strategies like forced sleep deprivation. He said Zimbardo “knew what he wanted and then tried to shape the experiment -- by how it was constructed, and how it played out -- to fit the conclusion that he had already worked out.”

Mark said Zimbardo wanted to show that middle-class young people “will turn on each other just because they're given a role and given power.” But he said that hypothesis was “a real stretch. I don't think the actual events match up with the bold headline. I never did, and I haven't changed my opinion.”

Zimbardo, who would later testify about human behavior in the wake of the bloody 1971 Attica Prison uprising in upstate New York, did not immediately respond to a request for an interview. Nor did Craig W. Haney, a psychology professor at UC Santa Cruz who was a graduate student of Zimbardo's in 1971 and a principal researcher on the prison experiment.

Haney has said he and his fellow researchers “weren't sure anything was going to happen” when the experiment began. “I remember at one point asking, ‘What if they just sit around playing guitar for two weeks? What the hell are we going to do then?’”

Speaking to the alumni magazine in 2011, he said the experiment’s most enduring finding may be how quickly “we get used to things that are shocking one day and a week later become matter-of-fact.”

He recalled that while preparing to move the prisoners, researchers realized that the subjects would figure out they were in the Stanford psychology building, not in an actual prison. So they put paper bags over their heads. “The first time I saw that, it was shocking,” Haney recalled. “By the next day we're putting bags on their heads and not thinking about it. That happens all the time in real correctional facilities.”

Haney said the experiment showed him the effects of dehumanization on incarcerated people.

“I try to talk to prisoners about what their lives are really like, and I don't think I would have come to that kind of empathy had I not seen what I saw at Stanford,” he said. “If someone had said that in six days you can take 10 healthy college kids, in good health and at the peak of resilience, and break them down by subjecting them to things that are commonplace and relatively mild by the standards of real prisons -- I'm not sure I would have believed it if I hadn't seen it happen.”

Blum’s new interviews are only the latest to take a magnifying glass to Zimbardo’s research. In 2001, British researchers who recreated the experiment suggested that guards acted tyrannically not because of the “toxic combination of groups and power,” but because of something more complex.

The turning point in Zimbardo’s experiment, they maintained, was when he stepped in as “prison superintendent” and told prisoners they couldn’t leave the study. Researchers Stephen Reicher and S. Alexander Haslam said this revelation disoriented the prisoners, who “ceased to support each other against the guards.” The tight group collapsed, allowing “tyrannical guards to prevail.”

In their modified re-enactment, dubbed the BBC Prison Study, prisoners actually challenged the guards’ authority, leading to a collapse of the prisoner-guard system. The participants then decided to continue the experiment as a “self-governing and self-disciplining ‘commune,’” but this too fell apart a day later, paving the way for the emergence of “a new tyranny” in the little lockup. In one key moment, a participant looked into the lens of a video camera and told researchers, “We’re having a military takeover of the regime that’s been put in place yesterday.” He demanded “full military uniforms” and vowed, “We’re going to run this prison the way it should have been run from day one.”

The researchers concluded that when people can’t create a social system that works, they’ll “more readily accept extreme solutions proposed by others” and allow an authoritarian ideology to take hold.

More recently, in 2007, Western Kentucky University psychologists Thomas Carnahan and Sam McFarland placed ads in several university newspapers, offering to pay volunteers for a “psychological study of prison life,” as Zimbardo’s ad had in 1971. They also invited another group to participate simply in a “psychological study,” without any mention of prison life.

Then they tested the respondents and found that those who replied to the “prison life” ad scored higher on measures of authoritarianism, narcissism, Machiavellianism, social dominance and “abuse-related dispositions of aggressiveness.” They also scored lower on measures of empathy and altruism, suggesting that the Stanford subjects may have showed up in August 1971 with traits of cruelty that not all of us necessarily possess.

“I’m a believer that the situation can lead people to do cruel things,” McFarland said in an interview. But he said a kind of selection bias may have played a part in the Stanford results. For one thing, Zimbardo openly sought subjects for a two-week, immersive experiment on prison life. “It just seems intuitively strong to me that some people would be more disposed to volunteer for such an experiment than would others,” he said.

McFarland, now retired, got the opportunity in 2006 to interview Sergeant Joseph Darby, the former U.S. Army reservist who blew the whistle on the Abu Ghraib prison scandal and who has publicly criticized U.S. military leadership at the facility. Asked by McFarland if most servicemen and women would have tortured and humiliated prisoners if they’d been stationed at Abu Ghraib, Darby flatly said: No.

“I could have taken any seven other soldiers from that unit and put them in the same situation and they would have acted honorably and professionally and performed their duties,” he said, according to an audio recording of the interview.

Eshelman, the guard who modeled his behavior on Cool Hand Luke, said he later regretted the mental abuse he inflicted. But when revelations about Abu Ghraib came to light, he said, his first reaction was, “This is so familiar to me. I knew exactly what was going on. I could picture myself in the middle of that and watching it spin out of control. When you have little or no supervision as to what you're doing, and no one steps in and says, ‘Hey, you can't do this,’ things just keep escalating.”