You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Two colleges in San Francisco are helping recent high school graduates who are not considered academically ready for college reach graduation on time.

San Francisco State University and City College of San Francisco have combined student services with a curriculum that emphasizes social justice as a way to improve student retention and completion. And both institutions are making sure faculty receive specialized training to provide that curriculum.

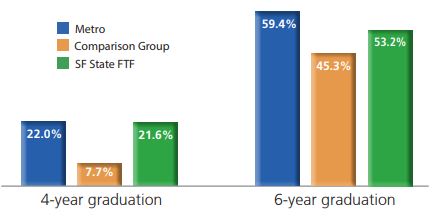

The Metro College Success Program is a two-year "school within a school" in which Metro Academies are organized within the colleges around a broad career or program area. Students enrolled in the academies at both the university and the community college outperform their peers. For instance, San Francisco State's six-year graduation rate is 53 percent, with a 45 percent rate for students with similar demographics -- low income, from minority groups or first generation -- as those in the Metro program. Yet students in the academies program had a six-year graduation rate of 60 percent.

At CCSF in 2017, according to program officials, 53 percent of Metro students transferred or graduated compared to 38 percent of similar student groups.

The program appears to be working in part because it manages to increase student engagement by offering instruction that is topically relevant to students' daily lives.

"While many student success approaches inevitably look at advising, tutoring and supplemental instruction … faculty teach a curriculum that's very contextualized and engaging to address real-world problems they experience," said Mary Beth Love, co-founder of the Metro program at San Francisco State and a professor of health education, adding that gentrification, for example, is a social issue that's integrated into the curriculum. "Many of our students are coming from communities in San Francisco where gentrification is a problem. It has emotional resonance for them and it makes learning and engaging real and connects to their lived experience."

Local high school students are recruited and apply for the more than 10 academies on a first-come, first-served basis if they're either low-income, first-generation or from an underrepresented minority group. Metro students are often all three, said Rama Kased, student services director for the program at San Francisco State.

For instance, 77 percent of Metro students at San Francisco State are first generation, 63 percent are low income and 58 percent are Latino. At City College, 57 percent of participants are first generation and 77 percent are from underrepresented minority groups. Both academies enroll many students who need remediation -- 90 percent of City College's Metro students and 76 percent of San Francisco State's.

Students enter and complete the program as a cohort. And the "wraparound" student supports are brought to them, so students don't feel they have to visit multiple locations or figure out where to go for coaching or financial aid.

As for the curriculum, despite each academy focusing on a program area like engineering, the sciences or health, students take general-education courses in addition to developmental courses with a goal of being college ready within a year. For example, if a student decides math in an engineering academy isn't for them, Love said, they can switch to a different academy without losing credit for the work.

And the social justice influence on the curriculum isn't just felt in courses like English -- a math class might examine the data behind stop-and-frisk policies.

"It makes the work of higher education very meaningful to young people who may question whether it's meaningful besides getting a job," Love said.

The program features 10 academies and has been funded to expand to 14. About a quarter of incoming students at San Francisco State are Metro students, while nearly 500 students at City College are enrolled in the program.

Although City College students can transfer wherever they please, if they're qualified, those who go to San Francisco State automatically join the upper-division part of the program.

"We have students who watch over our City College transfer students," said Vicki Legion, co-director of the Metro program and a professor of health and social justice at City College, adding that the nearby university is the two-year college's No. 1 transfer partner. "If someone hits a bump academically or gets on academic probation, there is a more advanced student who is watching out for them and can reach out and get them help."

Program tutors at the university are more advanced students and program alumni, Kased said, while the community college uses professional tutors. The third leg of the program centers on faculty development. During the summer, participating faculty members spend 45 hours in a learning community that prepares them for the socioeconomic needs of Metro students.

"Most programs leave the classrooms as they are and add services on top," Legion said. But to shift what's happening in the classroom and to provide more interactive and project-based instructions, she said, the academies also focus on helping instructors.

Since 2007 the Metro program has been funded by a variety of state and federal grants. The program's academies launched in 2009. And despite requiring more investment per student, it reduces overall institutional costs by helping more students graduate. For San Francisco State, the Metro program's progress in increasing completion has helped bring in additional state aid as part of the California State University system's Graduation Initiative 2025.

City College spends about $18,500 in the first two years on all students who meet the qualifications to apply for the Metro program. The program invests an estimated additional amount of $790 per year on each Metro student. Yet a college study found the program reduces overall costs by more than $24,000 for each student who completes.

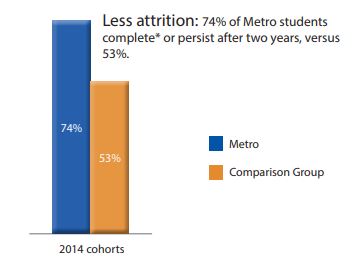

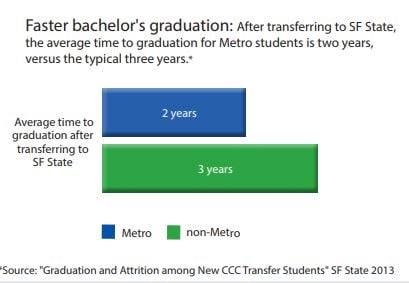

The cost savings come from reducing attrition, the time to graduation and the extra credits students take that don't count toward a degree. For instance, Metro students typically place into developmental math or English yet complete an associate degree on average within two and a half years. Yet the median time for California's black and Latino community college students to earn an associate degree is 4.3 years.

"Doing the same wrong thing over and over again and not getting students to graduation also has a pretty big price tag," said Love. "That additional investment to provide support and the engagement around learning with students is paying off on getting students through."