You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Student Press Coalition

You probably wouldn’t know if a scandal broke out at Taylor University, a Christian institution in rural Indiana.

Based on reading the student newspaper online, the university appears successful in many measures – donor money for scholarships skyrocketing, a new campus museum opening, an alumna taking a high-profile job.

But a several years ago, after a former professor sued Taylor for alleged racial discrimination, the story didn’t make it to the website of the student newspaper, The Echo, though it did appear in the print edition. Administrators blocked its publication.

As Taylor’s policy states: “the university cannot afford for questionable or negative Echo reporting to reach a worldwide audience.”

A university spokesman, Jim Garringer, said that the institution never censored The Echo’s website this academic year, and the policy as written is more “a formality” and will likely change or be struck down entirely.

But every week, Garringer still vets all the The Echo copy before it’s posted online.

Iterations of the same anecdotes can be heard at other Christian institutions nationwide, as some disillusioned Taylor journalists discovered in an informal survey of the student press at these places. They found that Christian college and university administrators often pressured student reporters to drop scoops, or guilted or dissuaded them from a story in subtle ways, perhaps insinuating pursuing controversial pieces would break with the values of the institution.

One former Taylor editor described this as pulling “the Jesus card.”

Religious institutions certainly don’t monopolize censorship in higher education. As some civil liberties experts have pointed out, some of the most egregious cases of free speech violations occur on public campuses from leaders concerned with public relations fallout. And legally, private colleges and universities aren’t even bound by the First Amendment. But reporters said that the culture on Christian campuses particularly discourages hard-hitting reporting that would sully their wholesome images, as the Taylor students have exposed.

Frustrated by Taylor’s policies, a group of current and former Echo staffers, and their supporters, decided earlier this year to survey other student editors who attend Council for Christian Colleges and Universities (CCCU) member institutions.

The students called themselves the Student Press Coalition. Initially, they wanted the answers to their questions kept private – they thought they could use the information to lobby the Taylor administrators to shift away from the current rules.

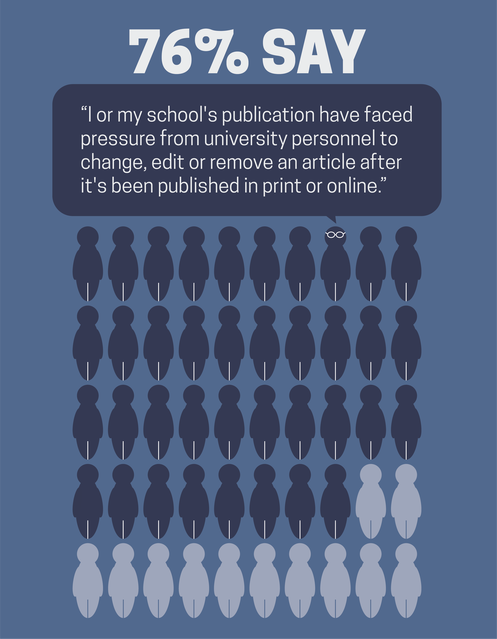

But after about 50 student journalists from 49 colleges and universities responded, and the group found widespread reports of suppression, it took the information public, said Cassidy Grom, a creator of the coalition and a former Echo editor. What was particularly startling: about 75 percent of those reporters and editors indicated that in some way, a university representative has encouraged them to change or remove an article after it was published.

CCCU declined interviews and provided a statement to Inside Higher Ed:

“CCCU institutions are committed to the academic and professional growth of their students, including those studying journalism and communications. Student newspapers are a valuable tool that allow students the opportunity to develop their interviewing, writing, editing and publishing skills, often under the mentorship of faculty advisors. Our institutions seek to balance student leadership and initiative with responsible mentorship and advising in the operations of their student newspapers to ensure sound journalistic principles and professional outcomes.”

While Taylor students were working as student journalists, and researching the other CCCU campuses, alarmed administrators, professors and advisers pushed back against their work, Grom said. She and others received emails (reviewed by Inside Higher Ed) asking about the contents of the informal study and warnings of going live with the Student Press Coalition website.

“We were under a lot of pressure not to move forward with this,” Grom said. “We were up against people we depend on for job recommendations, worked with for four years, our mentors, who we thought was our family. And they tried to use that in a lot of ways to make us feel inadequate.”

Grom said that during her junior year, when she was co-editor of The Echo, university officials blocked online publication of five or six articles that appeared in print. The case of the former professor suing Taylor in federal court happened before Grom was even the editor (the lawsuit was eventually settled) but it stuck out to her because the student reporter who worked on the story had researched it so well.

“But it was vetoed,” she said.

The Taylor spokesman, Garringer, said because the case will still be adjudicated, the university didn’t “want to comment,” acknowledging that the student journalists wouldn’t be implicated simply by writing about it. The lawsuit was and remains public information.

Alan Blanchard, associate professor of journalism, who became the adviser to The Echo in August, wrote in an op-ed in the paper that students have “great latitude” in selecting and writing stories “within generally accepted journalistic best practices.”

He wrote that the press freedoms students enjoy working at a college paper might exceed those in their professional career – even a newspaper owner or publisher can squash a story, “sometimes for good reasons, sometimes for not.”

Though Taylor’s policy is being debated, it still remains, and includes a line about stories not being published online that would “taint the public image of the university.” Garringer said that in the last couple years the university “has veered away” from the policy, though it hasn’t been changed, and he couldn’t pinpoint when it would other than “the not too distant future.”

This academic year, Garringer said administrators accepted it when he told them that he intended to allow stories to go online regardless of the content. The university wants to recreate a realistic experience as possible to a newsroom, adding that several journalism alumni have found success, including one who won a Pulitzer.

At other institutions, the purported censorship can range from explicit from simply cultural pressures to cease reporting.

Sometimes, administrators at the King’s College, based in New York, would step into the newspaper’s office and tell the staff to change a story or stop pursuing it, said Jessica Mathews, a former editor there.

“I have said we will keep it or continue to pursue it every time,” Mathews said, one of the more than dozen anecdotes the coalition made public.

Robin Gericke, an editor at the Asbury University student publication, told Religious News Services that when it published an interview with a gay alumnus about his experiences there, administrators confiscated the papers. They kept them locked up until the staffers showed them a letter from the man giving explicit permission to run the interview.

Several censorship cases at religious institutions have made national headlines.

In 2016, administrators at Saint Peter’s University, a Jesuit institution in Jersey City, shut down the student newspaper after it published a sex and love-related issue.

And Liberty University, where the president, Jerry Falwell Jr., is a staunch Trump loyalist, stopped the student newspaper from publishing a column critical of Trump. Falwell at the time denied the move was political, saying another, similar column had already run, and a sec ond column would be "redundant."

But Courtney Murphy, a student journalist from Whitworth University, said that the student newspaper tempered its coverage not based on intimidation from administrators, but because the university was so small.

“Most people know and like each other,” she said on the coalition website. “Because of this it often feels like we can't cover stories about RAs getting fired, athletes suspended, etc., because we don't want to hurt their reputation or they feel uncomfortable speaking with us.”

In a later interview, Murphy added that often students wouldn't want to talk to the paper during controversial events because it felt like everyone would know them. Murphy said she was surprised by the results of the survey because her experience had been so positive -- and pleased that an adviser never had to approve her copy. She added that CCCU institutions need to do work "across the board." A Whitworth spokeswoman, Nancy Hines, said the university was pleased the paper had autonomy and it could support student journalists.

Many students seek out Christian colleges and universities for the persona; attentio, and, of course, the religious aspects, even if Constitutional protections on freedom of the press aren’t extended to them, said Frank LoMonte, director of the Brechner Center for Freedom of Information at the University of Florida. As the coalition survey revealed, most Christian student publications (nearly 90 percent, according to the coalition data) are mostly or entirely funded through university dollars, giving the administrators even more control. Higher education professional associations, among them American Association of University Professors and the Association of American Colleges and Universities declared in 1967, that whenever possible, student press should be financially and legally separate from a university. If this isn't possible, then they should be allowed autonomy.

Some have argued, such as in this New Republic piece on censorship in religious institutions, that because their students receive some public dollars – Pell Grants and more -- that they should be obligated to give their students the same free speech rights as if they were on a public campus. The courts have ruled against this idea, said LoMonte, adding that he supports universities both public and private operating as "public trusts" under different rules than a private business. The Foundation for Individual Rights in Education, a civil liberties watchdog, noted that while accreditors often require institutions to pledge to protect free speech, but too often those rules go unenforced.

While religious institutions may not be censoring any more than their public counterparts, the overlay of church doctrine can complicate free expression on campus, LoMonte said. While some college administrators are often apologetic when they’re caught quashing student speech, religious leaders sometimes have little remorse in doing so because “they’re promoting a religious message,” he said.

“They can say with a straight face and feel justified that with the censorship, they’re doing something good,” LoMonte said.

But having a student newspaper that serves as public relations vehicle for the university won’t help the graduating students, he said – it won’t give them the clips they need to find a journalism job.

Grom, who graduated and will work at The Star-Ledger in New Jersey, said she ideally would love to see Christian universities mimic the processes of the publics. They could set up channels to file records requests and relinquish all editorial control, she said. Right now, she questions the value of a journalism degree from these institutions.

“From their perspective, from a business perspective, it doesn’t make sense to give us that much freedom,” Grom said. “Maybe it will result in negative coverage, or less dollars from donors. But anything less is to lying to us. It’s giving us a journalism that’s not mimicking the world. If we had more clear guidelines and freedom of press we could get Christians into these mainstream markets and do good work.”