You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Caiaimage/Robert Daly/Getty Images

At Haverford College last month, computer science students playfully but pointedly hung April Fool’s Day-inspired signs around campus, asking where their computer science professors were.

The faculty members weren’t missing, per se, since they were never there: Haverford, like the vast majority of other institutions, suffers from a computer science faculty shortage.

Haverford’s “dire shortage of faculty has created what can only be described as a crisis for students interested in computer science, lotterying us out of required introductory and upper-level classes,” a group of undergraduates wrote in a related letter to the campus’s Education Policy Committee published in the independent student newspaper, The Clerk.

“Without more tenure-track hiring, the enrollment situation will only get worse,” the students wrote. “The lack of faculty leaves glaring gaps in our curricular offerings -- as we lack experts in crucial areas of CS -- and effectively destroys the department’s ability to be part of a balanced liberal arts education for non-majors.”

The Haverford students raised particular concerns: the recent elimination of the computer science minor, gaps in permanent faculty subarea expertise and overenrolled lower-level courses among them. Yet the Haverford open letter echoes those written by students at Bryn Mawr College and Princeton University in the past few weeks alone. Students at Harvey Mudd and Pomona Colleges also recently have expressed public frustration with what they describe as inadequate administrative responses to the growth of their computer science departments.

The factors at play in the computer science faculty shortage are similar to those in other fields with lucrative job options outside academe -- a supply and demand story, but on steroids. To begin, there is relatively low Ph.D. production in computer science. Just 2 percent of all degrees conferred in the discipline are doctorates, compared to 8 percent in the sciences, math, technology and engineering fields overall, based on data from the federal Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System. Then there is relatively low entry into academe among those computer scientists who do obtain doctorates: just 29 percent, including nonteaching jobs, due to their ability to earn up to five times more in industry on average, according to some estimates.

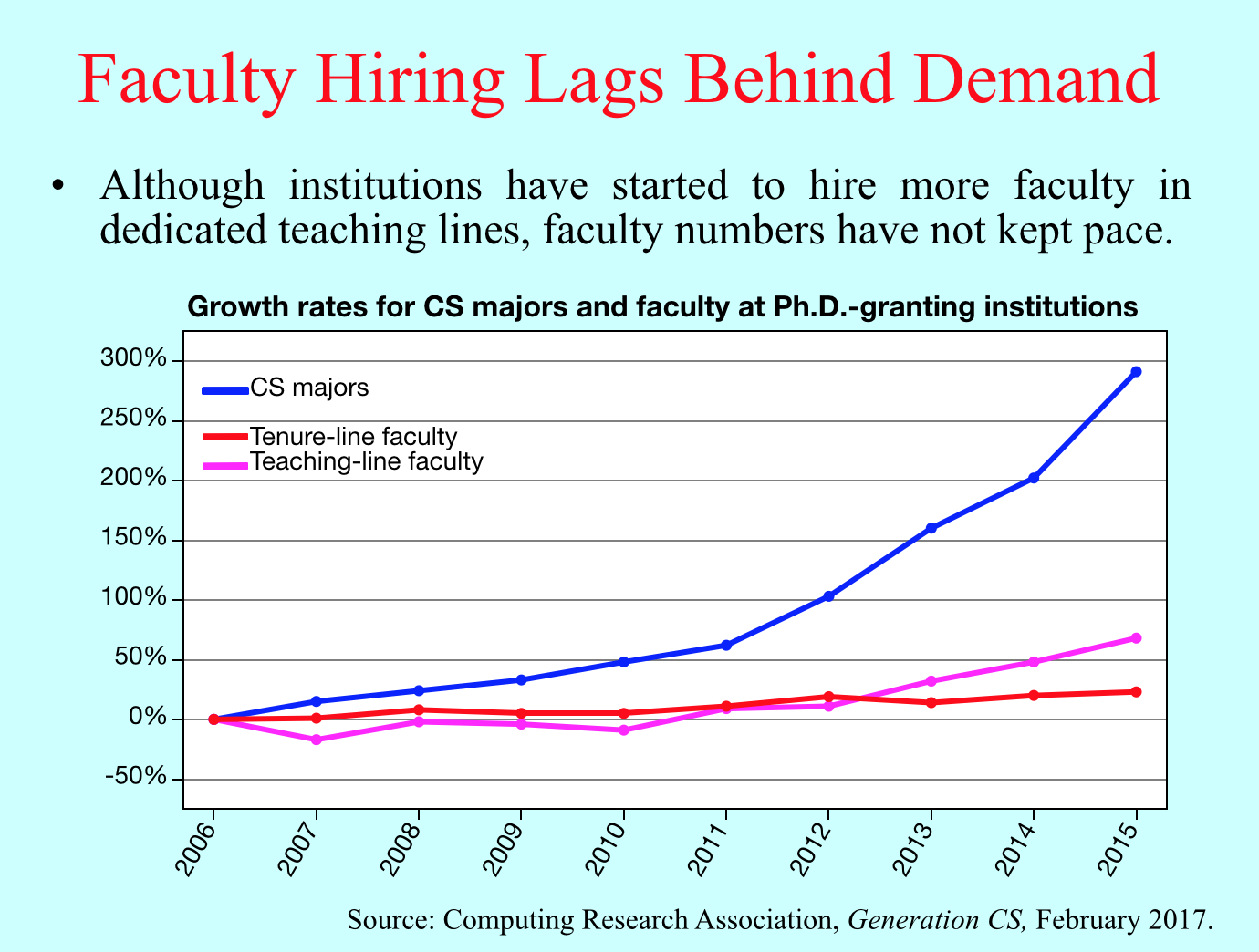

Intense market competition also awaits those computer scientists who yearn to teach. Eric Roberts, a professor of computer science emeritus at Stanford University, has been studying the issue for years and helped prepare a recent report for the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine on the growth of computer science undergraduate enrollments. Combining data from the Computer Research Association’s comprehensive Taulbee Survey and other sources, Roberts and his colleagues found that the rate of bachelor's-degree production in computing increased 74 percent between 2009 and 2015 alone, with an almost 300 percent increase at Ph.D.-granting institutions covered by the survey in particular. There have been historical blips, but Roberts says enrollments driven by both majors and nonmajors remain on an upward trajectory.

Hiring, meanwhile, has lagged behind that enrollment. According to the Taulbee Survey, 1,780 Ph.D. degrees in computer science were awarded in 2015. So if only 18 percent of Ph.D.s are taking teaching positions in academe, Roberts says, there are only 320 new Ph.D.s available to fill faculty slots in the 1,577 institutions that offer computer science degrees.

Those institutions can therefore expect to hire 0.2 new Ph.D.s per year, or one Ph.D. every five years. And since 80 percent of new Ph.D.s take positions at research-intensive institutions, colleges and universities that fall outside that category can expect to hire one new Ph.D. every 27 years.

A recent study in Computing Research News found that 18 percent of computer science faculty searches in 2017 failed entirely. Survey respondents at 155 institutions reported looking for 323 tenure-track positions and filling just 241.

Even Stanford -- a computing research epicenter where computer science in the No. 1 major -- isn’t immune from some of the factors plaguing the tenure-track faculty market. Roberts said in a recent interview that the department has lost twice as many faculty members to other opportunities in the last decade as it has in the previous 40 years.

Roberts has been involved in several interventions on his campus and elsewhere, including retraining non-computer science Ph.D.s to teach computer science. But he said that no “silver bullet” has yet emerged. To limit enrollments, some institutions have cut their numbers of majors and required students to apply to the program or meet a certain GPA threshold. To address staffing, some institutions employ computer scientists with master’s degrees to teach courses, but the market for those instructors is competitive, too. But many institutions are loathe to limit student access to the field and alternative staffing models don't work on campuses that pride themselves on hiring only instructors with terminal degrees -- namely liberal arts institutions.

A computer science professor involved in hiring at a liberal arts college who did not want to be identified by name or institution, citing concerns about affecting the department climate, said that beyond colleges' inability to meet industry salaries, some liberal arts administrators tend to overlook the discipline when it comes to adding faculty lines. Some underestimate the discipline’s growth, the faculty member said, while others may question its place within the liberal arts. The professor’s department now has 70 majors compared to 10 less than a decade ago. It has nine tenure-track faculty lines -- fewer than some other STEM departments with fewer majors.

The number of applicants for available jobs also has decreased, he said.

“In years past, we’ve had hundreds of applications; now it’s tens of applications for a tenure-track job,” he said. “The number of candidates who want these jobs is dwindling, due to the competition to hire from outside. Industry is willing to pay so much more than what we pay, and that’s clearly a problem.”

Still, Roberts said, some liberal arts institutions fare better in terms of hiring than doctoral institutions with lower research activity and, following that logic, community colleges.

San Francisco State University, for example, has had difficulty hiring tenure-track faculty members in recent years. William Hsu, chair of computer science on campus, said the market for Ph.D.s “has been extremely competitive,” and that the high cost of housing in the Bay Area is an additional challenge. The campus managed to bring on two new tenure-track professors this hiring season, however, Hsu said, to help support course enrollments that have doubled in the past five years.

David G. Wonnacott, chair of computer science at Haverford, said via email that the number of students interested in computer science “has grown much faster than most institutions have been able to increase their faculty.” Different institutions have responded in “different ways,” he said, “and I recommend that anyone who is interested in study of this field look carefully at the situation at each school they are considering. Now that we have accurate information about next year's majors, we are adding detail to our plans for next year, but I can't comment about them at this time.”

The Haverford students’ open letter asks the institution to add two new tenure-track faculty lines, noting that just two of three open assistant professorships were filled last year due to intense market competition. Chris Mills, spokesperson for Haverford, did not share salary information for the department but said it has seen a surge in student interest in a “very short period of time, from eight majors and 17 courses five years ago to 46 majors and 25 courses today.”

Staffing also has increased in that time, Mills said, but that is "only part of the solution." Working collaboratively with the computer science faculty and students, he added via email, “we believe that it will be possible to arrive at a comprehensive approach that also takes into account programmatic/curricular elements within the department as well as opportunities afforded by hiring multiple faculty members in related disciplines whose work is grounded in computational approaches.”