You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

The recession hit the University of Rhode Island hard. The public flagship quickly lost $26 million -- or more than 30 percent of its state support, which remains smaller than it was a decade ago.

Yet the painful budget cuts have had a silver lining at the university, where the need to be more efficient contributed to substantial improvements in student retention and graduation rates.

“It forced us to double down,” said Dean Libutti, the university’s vice provost for enrollment management.

Initially, the slashing hurt both student recruiting and retention, Libutti said. But these days more than half (52.3 percent) of URI’s undergraduates earn a degree within four years, an increase of roughly 14 percentage points since 2009. And those who don’t tend not to stick around much longer -- the average undergraduate at URI earns a degree in just under four years and two months, a statistic that even more selective public universities struggle to match.

The university’s retention rate for first-time students was 85 percent in 2016, a 6.3-percentage-point gain over about five years.

As is typically the case at universities that see gains with their retention and graduation rates, URI made a wide range of changes, few of them easy.

David Dooley, the university’s president since 2009, said the key was making timely degree completion a “matter of focus.”

URI spent money in the recession’s aftermath to bulk up its student advising capacity, on predictive analytics, degree mapping for each student and, in recent years, an ambitious overhaul of its general-education curriculum. The university also emphasized summer and January terms, offering online courses in those sessions.

Much of the effort was aimed at encouraging students to earn more credits per year and to help them not lose momentum when changing majors.

About three-quarters of first-time students at URI now earn 30 or more credits in their first year, with 68 percent earning 60 or more credits by the end of their sophomore year -- compared to roughly 45 percent of students at both points a decade ago.

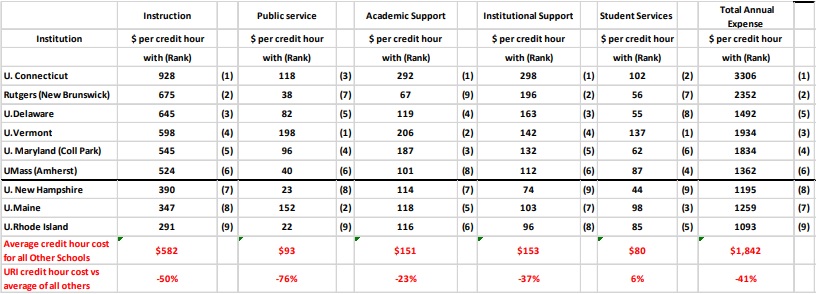

Better retention rates and credit production rates don’t just help students. URI cites federal data that show it spends substantially less on instruction, academic support and student services per credit hour earned than other public universities (see graphic, below).

Students who stay enrolled obviously spend more on tuition than those who drop out. And with enrollment hitting a record high of 17,382 last fall, the university said, its retention gains have generated enough funding to add 60 new tenure-track professor positions.

“They were thoughtful when they had to respond to adversity,” said David Bergeron, a former official at the U.S. Department of Education who has participated in a URI strategic budget and planning council. “It was both when they were cutting and making investments -- they were focused on student success.”

Practical Skills

URI’s overhaul of its general-education curriculum was unusually aggressive, experts said. The university completed the seven-year project in 2016.

The Faculty Senate’s goal for the new general-education program was to strive for “greater efficiency at the university as a means to address the increasingly competitive research sector and the challenging gap between student ability upon arrival and external demands for student competency upon graduation -- all of which results in an ever-increasing demand for teaching excellence.”

Every gen-ed course got the treatment, with student-learning outcomes as the Faculty Senate’s “intended centerpiece.” The university now has required and standardized learning objectives for each course (or competencies, a term URI officials use, which is rare at research universities) and is developing the accompanying assessments.

The final product is a “different way of thinking” for faculty members and administrators, said Laura Beauvais, URI’s vice provost for faculty affairs. It also has important practical impacts for students -- chiefly that general-education courses count toward all majors.

“If it’s required, it’s part of the major,” Beauvais said. “When a student finishes their gen-ed program, they have finished their gen-ed program.”

That might not seem so revolutionary, but it’s far from the norm in higher education. For example, at URI, a general-education course in the social sciences counts toward a major, meaning that the disciplinary program doesn’t require students to take a different social science course that’s specific to a major.

Besides not losing credits when they change majors, Dooley said, students benefit from a standardized, simpler pathway to a degree. The work was laborious for faculty members, he acknowledged. And the university, which is unionized, might have had a harder time getting it done if not for the turnover it had among faculty members since 2010, said Dooley, noting it was “easier to do” with its current faculty makeup.

Beauvais said the new gen-ed core helps students who transfer in, and graduates after they've left campus.

"This is a program in and of itself that prepares students to be lifelong learners," she said.

URI has participated in two summer institutes on general education that the Association of American Colleges & Universities hosted in recent years. Terrel Rhodes, vice president of AAC&U’s Office of Quality, Curriculum and Assessment, praised the university’s approach.

“They’re doing it well and not dictating it” to faculty members, he said.

The university stands out, Rhodes said, for how it incorporated practical skills -- such as understanding data and various categories of critical thinking -- in a systematic way into its learning outcomes and gen-ed courses.

“If you do this well, you’re going to have students staying longer and graduating,” he said. Asked how common this approach is among research universities, Rhodes said, “I wish I could say it was rampant, but it isn’t.”

He pointed to the Universities of Hawaii, Michigan, and Nebraska, Lincoln, as other good examples of using skills-based outcomes in their general-education core.

Rhodes said he wouldn’t be surprised if URI saw more retention gains as a result of the project.

“It seems to be paying off” for students, he said, “because they’re not just memorizing content.”