You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

iStock

Private colleges and universities discounted tuition for the 2016-17 academic year at higher rates than in previous years and continued their decade-long attempts to recruit and retain freshmen at a time of declining enrollment and increased competition for students.

The discount rate represents the portion of total tuition and fee revenue channeled back to students as grant-based financial aid. With growing discount rates, colleges also undercut their bottom line and slowed the growth of net tuition revenue, according to the 2017 Tuition Discounting Study, an annual report by the National Association of College and University Business Officers.

The study, which was released today, is a window into how colleges award scholarships and grants, and how tuition discounts affect the institutions’ financial health.

The study, which was released today, is a window into how colleges award scholarships and grants, and how tuition discounts affect the institutions’ financial health.

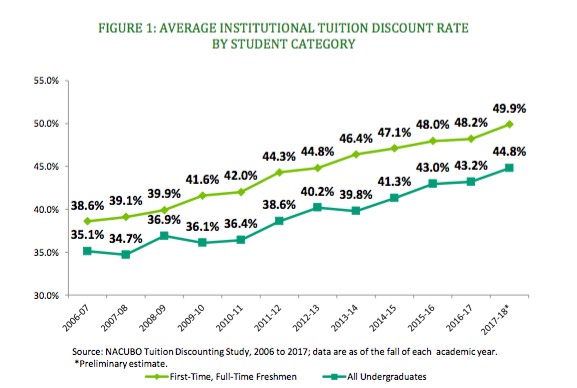

In 2016-17, the average discount rate for first-time, full-time freshmen reached 48.2 percent, and it is expected to have reached 49.9 percent in 2017-18, the highest level recorded since the tuition discounting study began. The discount rate for all undergraduates in 2017-18 rose to an estimated 44.8 percent, also an all-time high.

“It’s a story with two conclusions,” said Ken Redd, senior director of research and policy analysis at NACUBO. “First from the standpoint of the students, many more undergraduates are benefiting from more grants that are getting larger and covering a greater share of tuition costs. That’s good news for students and financial aid generally.

“But from the standpoint of tuition being used to pay for the grants, the colleges are getting more constrained and this has led to a strain in tuition revenue for many private colleges and universities,” he said.

Using inflation-adjusted values, net-tuition revenue, which accounts for the bulk of funding for private institutions, has been flat or declining for the last five years, the study determined. The decline was attributed to rising discount rates.

The study found that rates rose partly because a greater share of students received grants and the average grant covered a larger share of the average tuition price.

“About 89 percent of first-time, full-time freshmen received institutional grants in 2017-18, and the average grant award in 2017-18 covered 56.7 percent of tuition and fees, up from 55.3 percent in 2016-17,” the study states.

Kent John Chabotar, founding partner of MPK&D consultants, an education strategy and leadership consulting firm, and President Emeritus of Guilford College in North Carolina, said the study findings revealed the relentlessness of the increase in discount rates over the years.

Chabotar, who is also the former director of the Harvard Institutes on Higher Education, said as colleges give first-year students high discount rates, they’re then obligated to do the same for incoming freshmen the following year, creating a cycle of escalating annual costs.

“As the first-year rates skyrocket, the overall rate for the other students will rise as well,” he said. “As you continue to pump into the student body first-year students with very high discount rates, the overall discount rate for all undergraduate students is going to go up.

“This is most expensive when you talk about all students versus just the first-year students,” he said. “It’s a social good and a financial bad. The higher the discount rate, the less you have to spend on other needs.”

This challenge borne of market forces makes it more and more difficult for colleges to enroll and keep students.

“It’s a four-year problem -- or four-year opportunity, depending on how you look at it,” Chabotar said.

Although many private nonprofit colleges and universities award some aid based on factors other than financial need, the study found that “more than three-quarters of institutional grant dollars awarded in 2016-17 were used to meet students’ demonstrated financial need.”

Chabotar, who supports need-based aid, said the low percentage of non-need-based aid was among the most surprising aspects of the study.

“If most aid is need based and college students are needier, that percentage is just going to go up,’’ he said, referring to the growing gap between the full costs of college attendance and students’ actual financial need compared to the amount their parents are able to contribute.

“The study threw up its hands” on this issue, he said. “It’s a real worry for the schools, and it’s getting worse with enrollment downturns. Unless someone has a magic wand, there’s not much they can do about it.”

He said colleges and universities will have to find ways to cut costs in order to offset the slower growth in tuition revenue.

“I think colleges are inherently inefficient,” he said. “We spend every dime we make.”

As part of the study, chief business officers, or CBOs, at private nonprofit colleges and universities were asked to describe the strategies their institutions used in fiscal year 2017 to increase revenue. About 79 percent of CBOs said they used recruitment strategies for increasing enrollment, and nearly 73 percent used retention strategies such as improving academic advising. Additionally, about 64 percent reported using financial aid strategies, such as substantial changes in financial aid packages, and 20 percent used tuition pricing strategies.

Redd, the director of research and policy analysis at NACUBO, said no data are yet available to demonstrate if those strategies work.

Chabotar called such measures “all marketing and repackaging,” which doesn’t address larger needed changes to how academic programs are structured, how business is conducted and how facilities are managed.

“For instance, we reward colleges for having low faculty-to-student ratios. Costs are getting so prohibitive that there has been more openness to different size classes and different pedagogy,” he said.

Chabotar said he taught courses at the Harvard University graduate school of education that had as many as 80 to 90 students in individual classes. At Guilford his class sizes ranged between 10 and 15 students.

Small classes “are great,” he said, “but still I don’t think it’s worth spending as much as we do for small classes at the expense of the budgets. It not a good use of resources.”

Still, as the demographics of college students change nationally, and more students from families of modest incomes enroll, many institutions have responded by providing more financial aid.

“I guess the No. 1 question is, can institutions continue to increase their financial aid funding at the same time their tuition revenue is flat to declining?” said Redd. “We don’t have enough data in our study to answer that question directly.

“Increasing enrollment, improving retention, it will take a few years to know if they work to answer this sustainability question.”

A newer trend is to cut the tuition, he noted. “We have to see if that actually works.”

“The conundrum that schools have found in the past is that when they cut tuition, people thought the school has less value,” he said. “When you cut tuition, it also means less financial aid to students. Do students prefer lower prices and less financial aid, or higher prices with more financial aid? It remains to be seen.”